Nothing Left Inside

How America learned not to fear the inner self but lost its places of belonging

When I was in 1st grade, there was a sentence written on the classroom wall: “Shoot for the moon, even if you miss you’ll land among the stars.” For the longest time, I thought this was just a generic quote. To my surprise, it’s actually by Norman Vincent Peale.

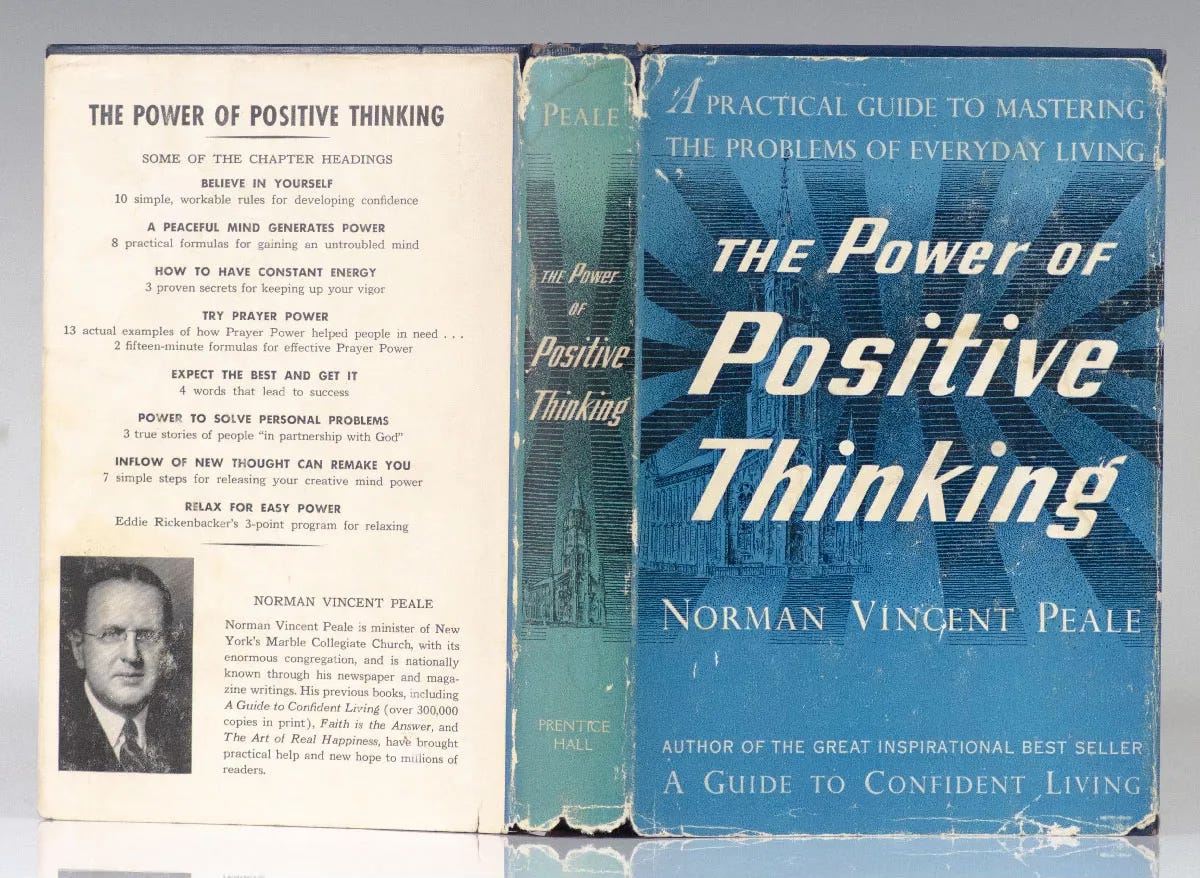

A Protestant clergyman, Peale became famous for selling positive thinking and relentless self-confidence. Known as “God’s salesman,” he spread his message through evangelical Christianity. His book The Power of Positive Thinking (1952) quickly became one of the bestselling self-help guides of all time.

Today, his words are still common in American classrooms and beyond. “Expect great things and great things will come,” reads one quote. “Empty pockets never held anyone back, only empty heads and empty hearts can do that,” reads another.

Peale was a confidant of many American elites in his long career. Five U.S. Presidents knew him personally and spoke highly of him.1 Practically all the most popular televangelists—like Billy Graham, Jerry Falwell, Robert Schuller, and Pat Robertson—saw themselves as his successor.2

But most famously, Peale made Donald Trump who he is. Trump considered himself to be Peale’s “greatest student of all time.”3 He often attended Peale’s church in Manhattan, whose book was commonly read in Trump’s home growing up. Peale also officiated Trump’s first marriage to Ivana, and Trump later co-hosted Peale’s 90th birthday.

Peale’s popularity is part of a larger story of how Americans came to understand themselves, which was then exported to the entire world. It’s a story of repression, then radical self-acceptance, and now confusion as places of belonging have suffered. It’s given way to a myriad of morbid symptoms: unhealthy parasocial attachments, neuroticism, a loss of meaning, and loneliness.

Suppressing the Self

When World War II ended, veterans came back to the United States victorious but also deeply disturbed. They now had to return to normal civilian life in what would become suburban America. Traumatized and anxious, this proved more difficult than many expected.

On the face of it, there was no reason to worry. The United States was a global superpower and booming economically. Everything at home seemed stable. But many elites privately feared that World War II had demonstrated a dark truth—that deep inside, the average person possessed nefarious desires which could explode again and upend society.

Such ideas had currency in the aftermath of World War II. Social theorists commonly speculated that it was the unleashing of unconscious desires that destroyed Europe.4 It was believed that the masses were excited to a frenzy, lost all reason, and so they became susceptible to fascism and communism. And the worry was, if left unchecked, something similar could take root again.

These fears were only compounded by the wave of Central European psychologists who came as refugees. They had experienced the psychic damage first-hand. They brought both cynicism from a life shattered by war and Freudian ideas of the unconscious to America. As Adam Curtis documents in The Century of the Self (2002), one such immigrant was psychoanalyst Martin Bergmann.

Bergmann began his practice by studying American soldiers during the 1940s. As he put it, the experience was like being “invited to a privileged tour into the inner soul of America.”5 But what he found unsettled him.

I learned that the ratio between the irrational and the rational in America is very much in favor of the irrational. That there's much greater unhappiness, much more suffering, it's much more a sad country than one would imagine.6

Bergmann said that through his studies, he finally came to understand what ran through “every little town in America.”7 Postwar America was a country wrought with deep psychic damage.

It’s observations like these that fill the psychological literature of the postwar period. The self is described as a place “prey to inner tensions” and “motivated by deep impulses which we do not understand.”8 The consensus was not that each individual should unleash their inner self, but rather suppress it.

Suppression took on the form of clear social roles. It was thought that if individuals conformed to accepted patterns of behavior, they would have a stronger sense of self. And by following these patterns, “they would be able to control the dangerous forces within them.”9

This became the purpose of establishment psychology in postwar America. The goal was to harmonize the individual’s different parts: “the domestic self, the business self, the religious self, and the political self”10 The trouble was that these different parts were “housed in one body but remain strangers to each other.”11 They had to be connected so they could work as one.

Therapy and treatment would allow these parts would be linked. And in doing so, the individual would finally “attain maturity.”12 To be a complete person meant no longer being bogged down by inner tensions. Whereas psychology today views individuals as ever-changing, postwar America valued maturing into one’s static, social role.

This environment was fertile ground for someone like Norman Vincent Peale. The Power of Positive Thinking (1952) communicated to the masses the need to suppress inner suffering through what is effectively self-hypnosis. His pithy statements on positive visualization were designed to keep the ego from falling victim to one’s inner demons.

Peale effectively sold “material acquisition and enhanced popularity as the avenues to happiness.”13 All you had to do is convince yourself.

By 1955, The Power of Positive Thinking had sold almost a million copies, outselling all other books besides the Bible.14 While popular among the public, Peale had many critics. In a scathing review from 1956, psychiatrist R. C. Murphy called out Peale for peddling fantasies:

With saccharine terrorism, Mr. Peale refuses to allow his followers to hear, speak or see any evil. For him real human suffering does not exist; there is no such thing as murderous rage, suicidal despair, cruelty, lust, greed, mass poverty, or illiteracy. All these things he would dismiss as trivial mental processes which will evaporate if thoughts are simply turned into more cheerful channels.

Mr Peale’s book is not only inadequate for our needs but even undertakes to drown out the fragile inner voice which is the spur to inner growth.15

However, Peale was the man for postwar America. Elites enjoyed a consensus within power unlike any other period in American history, so the psychological establishment suited the order of things.

Given how stable things were, it was too easy to believe that all this would last indefinitely. In many different fields, writers and theorists spoke of the repressed social situation as the new normal. The public was relatively subdued and passions were dormant.

With problematic desires kept away, sociologist Daniel Bell wrote in 1960 that the “ideological age had ended.”16 Now was the time for technocratic management at the top to run society like a machine. Others argued that the passive public was actually a sign that democracy was maturing.17 In the naive words of one observer, this was an “age of happy problems.”18

But as we know, what happened was the opposite. Just as many elites comfortably viewed this as the new normal, the American public suddenly erupted. The repression of the 1950s broke open as people rejected it and looked inward during the 1960s. “Kill the cop in your head.” “Tune in and drop out.” “Let your freak flag fly.” “Do your own thing, wherever you have to do it and whenever you want.”19

It’s a sensibility that we’re all familiar with today, and it would be America’s greatest cultural export.

The Radical Turn Inward

By the mid-1960s, American culture was in the throes of an individualist transformation. Nowadays, we all know its popular history. Breakthroughs came in music, film, television, fashion, and literature. Politics was hotly contested as more people asserted their dreams and independence. For many writers, America became a new and exciting unknown to be explored.20

Unsurprisingly, many activists at the time directed their anger toward what previously suppressed them: the old psychological establishment. To be deemed “insane” was like being a dissident, and some popular artists were former victims like poet Allen Ginsberg and musician Lou Reed.21 Psychoanalysis, once a booming business in America for celebrities and elites, was now being blamed for famous suicides like Marilyn Monroe.22

To the activists, the public had been kept docile by psychology, which allowed for the Vietnam War and other injustices to continue in silence. In 1969, the American Psychiatric Association had a revolt on its hands from some of its members, who accused its therapists of pacifying the public.23

One major influence on the dissidents was renegade psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich. His book The Mass Psychology of Fascism would become something of a Bible for 1960s activists. “You’ve locked up the lunatics and the world is run by you normal people,” he wrote, “then who’s to blame for all the trouble?”24

It wasn’t that the activists were necessarily wrong, but they failed to recognize the limits of the ego. Many of the most radical experiments in “self-love” were workshopped in California. They would be part of the greater Human Potential Movement, which popularized terms like “humanistic psychology,” “holistic health,” and “personal growth.”25

In The Century of the Self, Curtis documents the leading institutes that specialized in letting free the inner self. One such organization, the Esalen Institute, became a fixture of the counter-culture by the late 1960s. Sessions were conducted in groups, often as emotional venting to be “born again.” In 1967, over 4,000 people traveled to beautiful Big Sur, California to be transformed at Esalen.26

The Esalen Institute was really just a test run of what was to come. Former salesman Werner Erhard would take the Esalen model and apply mass marketing techniques to it, transforming it into a proper commercial enterprise. In 1971, he created the Erhard Seminars Training, Inc (called “est”).

The intense sessions at Erhard Seminars were intended to break down every layer of the self until you reached the “core.” The purpose was to shed all societal obligations and hammer into you that it was only you who created reality. During the 1970s, “singers, film stars, and hundreds of thousands of ordinary Americans underwent the training” as its methods were exported to Europe and beyond.27 Each Erhard graduate was actively encouraged to recruit more members after completing the sessions.

One journalist for Harper’s Magazine described attending an Erhard Seminars event:

… Restless, impatient, volatile; one could feel rising from it a palpable sense of hunger, as if these people had somehow been failed by both the world and their therapies.28

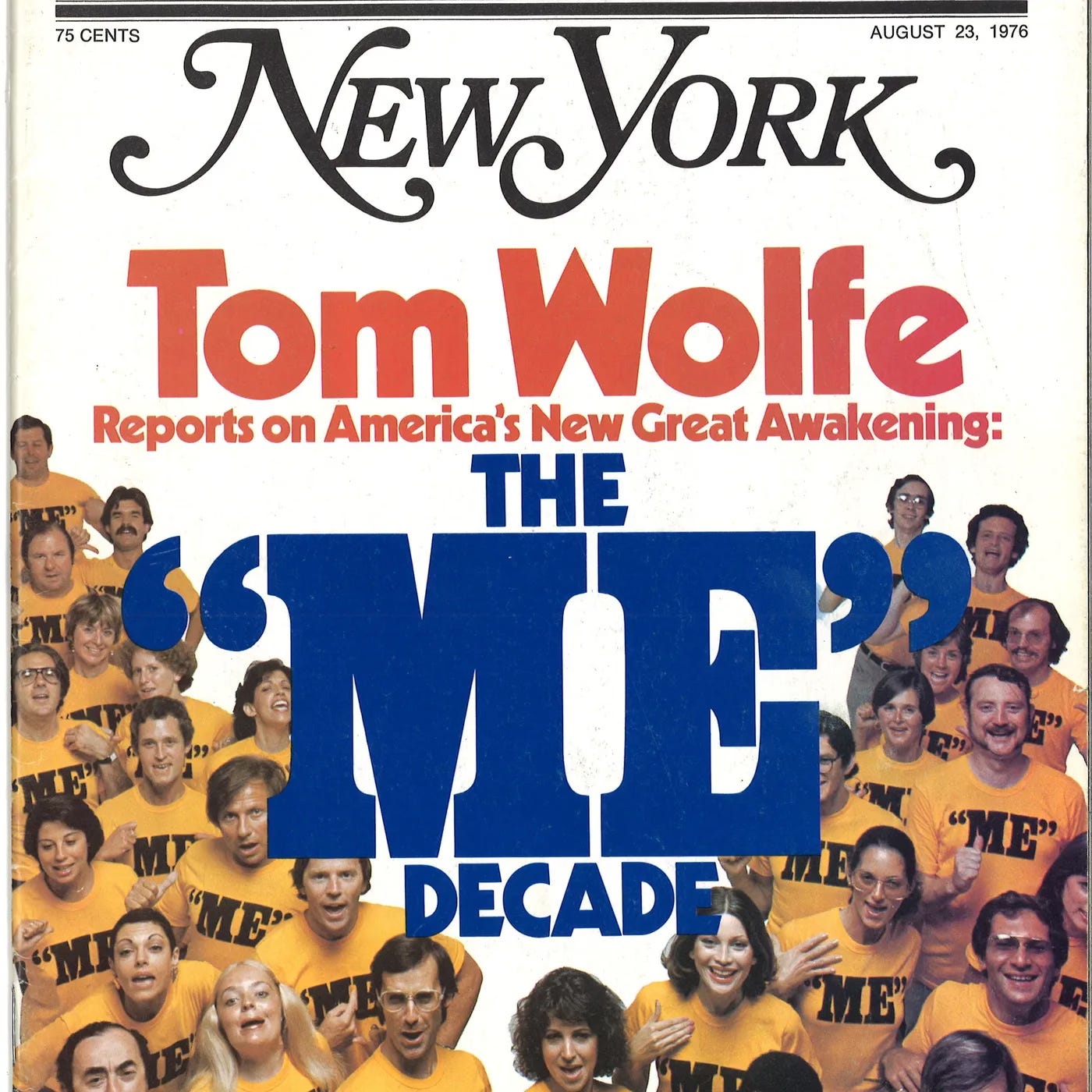

Cultural critic Tom Wolfe summarized the appeal in simple terms: “Let’s talk about Me.”29

The California experiment would ultimately succeed in reshaping the American psyche. In the words of one therapist, it was like a religious awakening.

In many ways, psychotherapy has taken over the function of religion.

Americans are becoming alienated and are hungering for a sense of meaning, identity, happiness, and even salvation. [People] want more from therapies and therapists. Therefore, the therapist is supposed to take over the function and roles of shaman, guru, wiseman, minister, rabbi, or priest.

We are expected to help with spiritual matters on the one hand and scientific on the other…30

This new sensibility trickled to the very top of American society. One of its converted advocates later found himself in a major position of power.

In 1986, John ‘Vasco’ Vasconcellos—an alumnus of Esalen and a California state assemblyman—became famous for successfully creating the first government task force dedicated to “boosting self-esteem.”31 By 1990, the committee’s self-esteem report found support from the likes of Bill Clinton, Barbara Bush, Colin Powell, and Oprah Winfrey.32 Other states and schools would implement similar self-esteem programs that decade, with one consequence being rampant grade inflation.33

Vasco’s efforts are a fitting dead-end of the American turn inward. It is as if Peale’s empty philosophy was repackaged, made better for the permissive liberal age.

No Place to Go

The turn inward came during a time of intense political upheaval in America. It was believed that the new individual would also create a new society. However, by the mid-1970s, political dreams died amid scandal and corruption at the top. Confidence in institutions collapsed and never recovered.34

As fewer and fewer people looked to politics to actualize their dreams, what remained was their sense of reawakened individuality. Naturally, this became a powerful stimulant for American business. Marketing firms went to work inventing personality questionnaires, trend forecasting, focus groups, and psychological profiles to better sell to this new public.35

Yet, the search inward meant little without places of belonging. The new American individual, despite having more consumer choice than ever before, looked upon a country transformed by anti-social ends. Downtowns were dismantled in virtually every city to make way for highways.36 Many cities themselves went bankrupt as people left.37 Public spaces slowly gave way to commercial spaces to suit cars from suburbia.38 Now even these commercial spaces, like malls, are practically gone.39

The story has a tragic undertone to it. The public that desired authenticity and self-actualization slowly found itself without places of belonging. In 1995, political scientist Robert Putnam recorded that between 1974-1994, there was a minor but significant decline in group activity in virtually all areas: “hobbies, sports, professional, youth, sorority/fraternity, literary & arts, school services, political, church-related, labor unions, and others.”40 This drop is today just a blip compared to the steep decline of the last 10 years, which has been covered extensively.41

It’s a trend that sociologist Ray Oldenburg already saw in the late 1980s. In The Great Good Place (1989), he starts his book by stating, “the problem of place in America has not yet been resolved.”42 Oldenburg was responsible for popularizing the idea of “third places.” Third places are spaces to socialize that are neither school nor work. Writing at the tail-end of the Reagan years, Oldenburg was already lamenting the decline of third spaces and informal public life.

As Americans learned not to fear their inner selves, they effectively gave up on the world. Politicians, too, spoke in the language of the new individual and not of collective interests.43 Before his death in 1994, writer Christopher Lasch looked at this decades-long dismantling of the public sphere with unease. He speculated that the disappearance of third places had directly caused the decline of participatory democracy.44

“Increasingly, conversation has no place in America,” Lasch wrote.45 By “conversation,” Lasch meant those discussions where one is exposed to healthy difference. Oldenburg recounts a similar story. As one friend told him, eavesdropping in third places growing up was what “gave her a lifetime interest in politics, economics, and philosophy, none of which were part of the world at home.”46

The adoption of the internet came right around the time Lasch was writing. For all the blame given to it for causing anti-sociality, the internet came online as places of belonging were already eroding. For many today, the internet is their third place. But even this third place is now suffering the same threats that dismantled the actual, physical third places decades ago.47

The internet has accelerated anti-social trends, but its effects would not be so severe had the public had a place to begin with. The online world holds a mirror to what we lack in the physical world. The internet functions nowadays not as a third place, but instead as a conduit for frustrations from there not being one.

The self is not a substitute for place. And without a place, there is little left inward to console. Its symptoms are apparent: the rapid rise in loneliness, anxiety, depression, and other mental ailments.48

An Empty Surprise

There was definitely something repressive about postwar America. But by that same token, there was definitely something equally empty about thinking all the answers lied inward. I’m reminded of an analogy made by philosopher Slavoj Žižek about the chocolate Kinder Surprise Egg.49

Popular in Europe, it’s a chocolate egg whose inside is hollow but with a plastic surprise toy in the middle. Most people don’t bother to eat the chocolate first. Instead, you just break it open to know what’s inside. Oftentimes, you don’t even really want the toy. You just want the surprise.

I’m not going to outright say what’s the chocolate and what’s the toy. But the inside is a void of desire. There is no “it” there that will satisfy and you’re left wanting more. Maybe out of spite, you actually eat the chocolate. It may even make the chocolate taste a little bit better. Perhaps you also realize the chocolate isn’t something made just to hold the inner surprise, but worth something on its own. After all, it’s only because of the chocolate that you get the surprise. Funny enough, the Kinder Surprise Egg is banned in the United States.

The inward turn in America was a cultural blueprint exported to the entire world. And one can understand why, the ego is very seductive. It sells, but gives little meaning on its own. By looking at life through the prism of the self, at the expense of the world, a person is left stagnant and infantile. You can only dig inside yourself so much until you have to venture outward. Said simply, “For what life have you if not a life lived together?”50

Presidents Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, and H. W. Bush all admired Peale. In 1984, Reagan awarded Peale the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Ira Katznelson. Desolation and Enlightenment: Political Knowledge After Total War, Totalitarianism, and the Holocaust (2020), 445.

Century of the Self (2002). Full transcript, pg. 16.

Century of the Self (2002). Full transcript, pg. 16.

Century of the Self (2002). Full transcript, pg. 16.

Irene Taviss Thomson. Individualism and Conformity in the 1950s vs. the 1980s (Sept, 1992), pg. 501.

Century of the Self (2002). Full transcript, pg. 18.

Irene Taviss Thomson. Individualism and Conformity in the 1950s vs. the 1980s (Sept, 1992), pg. 501.

Irene Taviss Thomson. Individualism and Conformity in the 1950s vs. the 1980s (Sept, 1992), pg. 501.

Irene Taviss Thomson. Individualism and Conformity in the 1950s vs. the 1980s (Sept, 1992), pg. 502.

Murphy, R.C. “Think Right: Reverend Peale’s Panacea” (May 7, 1955). The Nation.

Daniel Bell. The End of Ideology (Harvard University Press, 1988), 403.

Books like The Civic Culture (1963) and Political Participation (1965) argued that passive apathy was a sign of democratic maturity right on the eve of the 1960s counter-culture going full swing.

Irene Taviss Thomson. Individualism and Conformity in the 1950s vs. the 1980s (Sept, 1992), pg. 508.

The hippie philosophy as profiled in Time (July 7, 1967).

As I documented in my past essay On Weird America, New Journalism viewed America as a strange new world to be rediscovered in the 1960s. “In my own country, I am in a far-off land…” wrote Hunter S. Thompson in Hell’s Angels (1967).

Many of the Beat Generation were victims of psychiatry or considered mentally disturbed by the psychological establishment, like William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac.

Wilhelm Reich. Listen Little Man! (1945, republished in 1965).

Same as above ^

Century of the Self (2002). Full transcript, pg. 37.

Between the late 1960s and 2004, the proportion of first-year university students claiming an “A average” in high school rose from 18% to 48%, even though SAT scores had actually fallen.

According to Pew Research Center, public trust in government reached an all-time-high in 1964 with 77% believing that the federal government does “what is right just about always or most of the time.” The drop-off that occurred in the years ahead is nothing short of extraordinary. By 1979, Pew Research records that just a quarter of Americans trusted their own government.

Century of the Self (2002). Full transcript, pg. 38-42.

I covered this for Palladium Magazine in 2023. It was a process that began in earnest in the 1950s and affected virtually every American city, both big and small.

New York City, Boston, Chicago, Minneapolis, and Atlanta each lost some 10 percent of their populations during the 1970s. St. Louis, Cleveland, Buffalo, and Detroit shrank by some 20 percent.

Sharon Zukin. Landscapes of Power: From Detroit to Disney World (1991), pg. 142.

By the 1990s, malls began to transition to a more “upscale” clientele to discourage loitering, setting in motion the decline that would follow by the 2000s.

Robert Putnam. Tuning In, Tuning Out: The Strange Disappearance of Social Capital in America (Dec, 1995).

I previously covered the steep drop since the 2000s in my essay The Social Recession: By the Numbers.

Ray Oldenburg. The Great Good Place (1989), pg. 3.

Both Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher spoke in these terms. As Thatcher famously said, “Who is society? There is no such thing.”

Christopher Lasch. Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy (1994), pg. 123.

Christopher Lasch. Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy (1994), pg. 123.

Christopher Lasch. Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy (1994), pg. 123.

The “enshittification” of the internet has been talked about to death online, but it bears resemblance to what already happened to the physical world. I touched on this theme in my essay The Internet Is Like a City (But Not in the Way You’d Think).

Most of this data is compiled in my article The Social Recession. Recently, FT reported on the increase in neuroticism and non-conscientiousness in people.

Great essay, as usual. Mr. Cebalo you are spoiling us!

The individualism of the 60s and the distrust of government from the Vietnam war and the Nixon\Watergate meltdown, found its energy in the pursuit of money and power. Rather than find continuing ways to reform capitalistic society for the good of all, the new found individualism served to propel money and power to the forefront of American culture. As the greatest generation faded into the background, the boomers, and our love of self and money, came forward.

Money and power became our gods. As Mr. Cebalo points out, the places and spaces for informal discourse became less available. Replaced by the ultimate intelligence vacuum of the internet. And now brought to a fevered pitch by social media. The rise of evangelical Christianity played into that as anyone who accepted Jesus Christ as their savior was free to take care of themselves and be forgiven. Moral action and ethical behavior was replaced by that acceptance. And mainstream theology requires Chri

Moral clarity in deeds not in words.

Our leaders, therefore, are a reflection of who we are as a society. They do not exist in a vacuum apart from us. I have told my children since they were small, you know you are a mature adult when you can look in the mirror and accept you are the sum of all your decisions. American leadership and culture are the sum of all our decisions.

Great analysis. I think there’s something about this power of positive thinking in American life that’s starting to turn sour. I’ve been thinking about Elizabeth Gilbert’s dark new book as an example of this. It’s interesting that the big takeaway of that book is her discovery of AA, which serves for her as a form of communal spiritual belonging. Part of me wants to believe Americans are ready to recreate more of those spaces of belonging, another part of me worries that it’s too late.

On inwardness: I would say that it doesn’t always need to be individualistic. In communal spaces of belonging I think that moments of inwardness, or figures of inwardness, have their role and place. What seems terrible about America of the late 20th and early 21st centuries is the way that inwardness has been, as you note, privatized and turned into a zone of commercial exploitation. It’s become less a resource for connection and more a form of private property to develop and enhance.