On Weird America

Every few generations, there comes a time when one's country is rediscovered with new eyes

I recently watched an episode of an old TV show with my parents that used to premiere in Yugoslavia. Called Caravan, the series ran from 1963 to 1983 and took audiences to little-known parts of the country. The host, Milan Kovačević, spoke in a dry and matter-of-fact tone. With each episode, he introduced parts of Yugoslavia to its own citizens, and implied it was all part of a collective bounty to be enjoyed.

Yugoslavia obviously no longer exists. But if that impossible country were ever to survive, it had to rediscover itself. The attempt came during the relatively stable years of the 1960s and ‘70s when my parents grew up. It wasn’t enough. By 1981, less than 10% of citizens exclusively identified as “Yugoslavs,” but at least it made for some good TV.1

The United States has also undergone periods of finding out who it was all over again. Nowadays, there’s evidence to suggest that another spring of rediscovery may be long overdue. In 2019, a majority (60%) somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement, “I feel like a stranger in my own country.”2 There hasn’t been a poll on this question since, but we can assume that the pandemic and the ensuing social fallout haven’t eased the feeling.

In the 20th century, the modern United States rediscovered itself twice: after the Gilded Age and during the late 1960s and ‘70s. I’d like to briefly go through these two eras and end with some thoughts on where the next one may lead.

American Realism (early 1900s)

Out of the Gilded Age, the United States emerged as a new country. By the early 1900s, it was a major industrial power with a large working class for the first time. Almost 50% of the population now lived in cities.3 The immigrant population doubled in just a few decades, causing social rifts.4 Deepening class inequality was upending American society and labor strife was common. The political environment was tense. It was an opportune time for the United States to be rediscovered, and the medium of choice was painting and photography.

A group of realist painters came together in New York City to capture these sweeping changes. Known as the Ashcan School, their subject matter was America’s working class and those who lived on the margins: tenement housing, slums, industrial work, taverns, and street life in the city. The artists jokingly called themselves the “apostles of ugliness.” The founder of the movement, Robert Henri, viewed art like journalism and sought to depict the new America in an uncompromising, brutal way.

Alongside the Ashcan School, photographers also took on the task of rediscovering America. Photography was then an emerging medium, and the hope was that it would ignite social reform. The images captured by Jacob Riis, compiled in How the Other Half Lives (1890), were a major influence on the Ashcan School. Others, like Lewis Hine, documented America’s child laborers. The genre was loosely called “social documentary photography.”

However, unlike these socially-conscious photographers, the painters of the Ashcan School were not muckraking political activists. They were instead bohemians. Aside from occasionally illustrating for left-wing magazines like The Masses and frequenting socialist saloons, they did not have a political manifesto. They just sought to document American life as they saw it.

Still, the outcome of American realism was ultimately political. By the 1930s, American rediscovery was institutionalized properly by New Dealers who federally employed photographers to "reintroduce America to Americans.”5 Some 65,000 photographs were taken, many of which are today famous and easily recognizable.

New Journalism (late 1960s-1970s)

The transformations of the Gilded Age provoked the first rediscovery of the modern United States. The late 1960s brought the second, and this time its primary medium was the novel and text.

Again, the United States quickly changed in just a few decades. The relative affluence after World War II led to suburbanization on a mass scale: cost-efficient housing for families outside the cities, connected by newly built highways. Levittown, Long Island, was constructed as the “ideal” example of a planned, mass-produced white suburb.6 Suburbanization had effectively created a new type of American.

In 1956, sociologist William H. Whyte described this new American man as the “organization man.”7 Gone was the rugged individualism of old America. This new American was instead an individual suited for middle management and the rank-and-file, strictly adhering to his organizational duties: be it corporate, government, church, university, or neighborhood. By the 1960s, all that suppressed energy erupted with the first generation to be raised in it, the Baby Boomers.

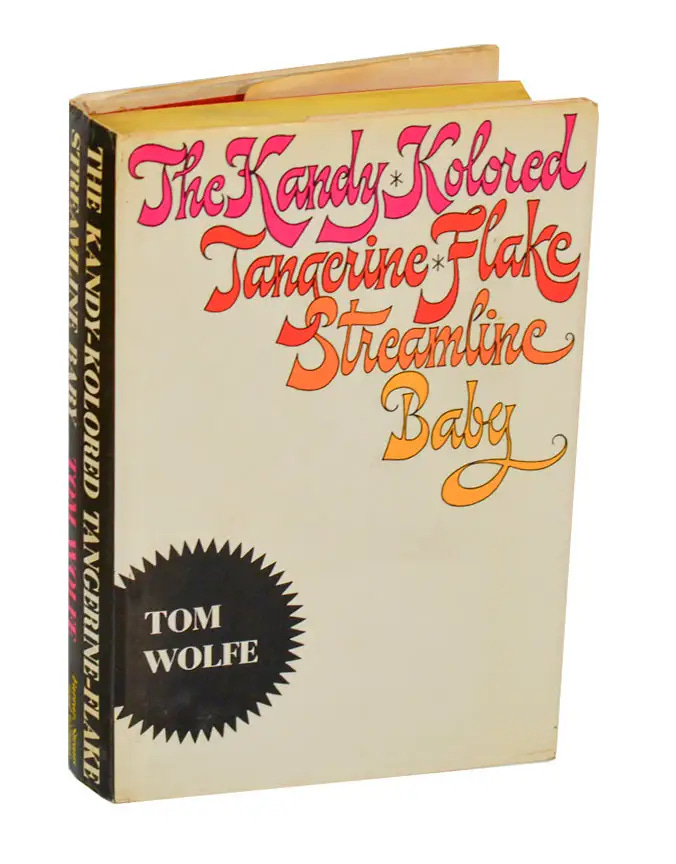

The United States was then rediscovered by New Journalism. Previous journalists sought to be invisible. These writers instead embedded themselves in America’s underground. Tom Wolfe called it “saturation reporting.” The idea was to shadow people for long periods until the truth would finally reveal itself. His contemporary, Norman Mailer, popularized the “non-fiction novel.” All the drama and flair of the original fiction novel were reapplied to real life through reportage, and it proved to be incredibly popular.

Because of the richness of America’s underground, the late 1960s and 1970s were the golden age of the essayist and social critic. Many of their observations are now a core part of the American popular imagination. Because these writers themselves no longer understood America, they had no choice but to unearth what was hidden. As Joan Didion wrote in 1967, she came to San Francisco simply because “the world as I had understood it no longer existed.”8 Hunter S. Thompson’s first non-fiction novel Hell’s Angels (1967) similarly opens with a poem that reads: “In my own country, I am in a far-off land…”9

Weird America (2020—?)

It’s now been some 60 years since New Journalism came on the scene. And, like Joan Didion said then, many would today also agree that the world as they once understood it no longer exists.

When traveling outside the United States, I often hear this country described as “weird” or even “dangerous.” This is because America’s number one export nowadays is its politics and culture war.10 Wherever you are, it is impossible to browse social media without being exposed to America’s collective psychosis. People often know more about the inner dramas of the United States than their neighboring countries. Even in Afghanistan, youths after the Taliban takeover relished mocking people as “soy boys” and making fun of “they/thems” (even though this has zero cultural relevance to them).11

Americanism is everywhere, but opinions are siloed based on what you browse. Overexposure also produces fatigue. For both its citizens and those living outside the United States, America has lost its veil. Some 40 years ago, the average person outside the West might have believed it to be the land of milk and honey.12 But America’s dysfunction is now exposed, and what were once greener pastures have been replaced by morbid fascination. “What is even going on there?” Whatever it is, things are said to be “happening” here. America is the social laboratory for everyone to gawk at, mock, or copy.

I’d call the current wave of rediscovery “Weird America.” According to the late writer Mark Fisher, weirdness radiates at the edge of worlds. It is the presence of “that which does not belong.”13 The pulse of Weird America is chaotic, paranoid, socially aloof, low trust, and consumes information as an identity. Because it feeds off attention, its primary medium will be documentary-style shows and video content. One of the pioneers of this form was Louis Theroux’s BBC Two series, which started in 2003.14 Today, the most popular example is Andrew Callahan’s shows All Gas No Brakes and Channel 5, along with his documentary This Place Rules (2022).15

Film has only started to touch on Weird America. Arguably, one of the first to explore it has been Eddington (2025) directed by Ari Aster.

Set during the pandemic, the film is a mix between a Western and the pathologies of 2020s America: doomscrolling, hyper-political polarization, empty spirituality, grifters, surreal violence, conspiracies, paranoia, and deep loneliness, set in a small gun-slinging town in New Mexico. All of these are coordinates of Weird America. For what it is, it was the first film I’ve seen that illustrated today’s America as a void for the audience’s tragic amusement. I don’t even know if I liked all of it, but it was different. I left the theater feeling empty.

But Weird America is just getting started. Because the media environment is so decentralized, most of its content will not be curated. We will be exposed to it indirectly through our online consumption. There will be chroniclers, whoever they are, seeking it out. Some of them will be writers as well.

The first rediscovery of modern America exposed its exploited underclass. The second rediscovery sought to understand its new individualism and the underground. The third is about picking up the pieces of a frayed social environment with no center holding it together. The rest of the world watches with fascination, maybe because they see their future in it too.

This is from the official 1981 census, but it doesn’t tell the full picture. A poll conducted from 2010 to 2014 actually showed that almost half of citizens in former Yugoslav countries admitted to once feeling like “Yugoslavs.”

The poll asked respondents whether or not they agree with the statement: “Things have changed so much that I often feel like a stranger in my own country."

Photographers were hired by the Farm Security Administration with the stated goal of “introducing America to Americans.”

While planned suburbs like Levittown started as exclusively white neighborhoods, suburbanization now crosses racial lines. Some 45% of suburbanites are non-white. The average American is a suburbanite.

The Organization Man was published in 1956 and became a bestseller. It was especially popular among dissidents who were critical of this new conformist American way of life.

Taken from the preface to Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968).

Hunter S. Thompson opens Hells Angels (1967) with this translated line from French poet Francois Villon.

David Oks writes about his 2023 experience with the youths of Kabul, Afghanistan in The West Lives On in the Taliban’s Afghanistan.

This perception of America gives me an excuse to tell an old ex-Yugoslav joke about Montenegrins (and their legendary laziness):

A Montenegrin man hears that America is a country of milk and honey, and that money just grows on trees. So, he says to himself, “I’m also going there to get rich.”

He gets on the plane and heads to Los Angeles. As he gets off the plane, he sees a wallet full of cash on the sidewalk.

He kicks him and says, “Come on man, there’s no way I’m working on my first day!”

Mark Fisher contrasts the weird and the eerie in his book The Weird and the Eerie (2016). Unlike weirdness, eirieness radiates from lost worlds, ruins, and empty space.

In his BBC Two specials (2003—), Louis Theroux would bring his gentle and confused British demeanor to strange American places, talking to gamblers, Nazis, prisoners, and brothel owners, among others. The series is still ongoing and recently covered Israeli settlers in the West Bank, some of whom are Americans.

Some other shows have taken inspiration from Andrew Callahan, like no cap on god on YouTube.

Ironic that the video is maybe the worst medium to capture a cultural mood mediated by people alone in their rooms consuming text, images, and videos of other people in rooms talking to a screen. A novel would capture that much better

What's the significance that the two countries which have most fascinated Nobel laureate Peter Handke in his long career have been the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the United States of America?