The Return of the World's Fair

With Saudi Arabia winning the 2030 bid, the global spectacle may be coming back in a big way

In the spring of 1873, a Japanese delegation arrived at the World’s Fair in Vienna, Austria-Hungary. Five years after the Meiji Revolution, their attendance was meticulously planned. A special government bureau was created, and a team of engineers accompanied the delegation. The exposition was even given a test run a year beforehand in Tokyo.

Yet for Kido Yakayoshi, one of the founding Meiji statesmen, the event caused a kind of existential crisis. As he wrote in his diary during the visit, “The people of our country are not yet able to distinguish between the purpose of an exposition and a museum.”1 Amid the industrialized Western powers, Japan was merely showing its cultural wares. Rather than let itself be perceived as a museum-like object of the past, Japan had to prove itself as dynamic.2

Meiji Japan was perhaps the first non-Western state to deeply understand the power politics inherent to world’s fairs. From 1873 to 1910, it spent an exorbitant amount on exhibitions, participating in no fewer than 29 different major international showings throughout the United States and Western Europe.3 During this time, world’s fairs were largely about industrialization and invention, and the events served as critical reconnaissance for Japan’s modernization efforts. By the early 20th century, it stood competitive outside European empires both economically and militarily. Much like for the other great powers, the fairgrounds soon became a place for Japan to showcase its colonial aspirations, specifically in Manchuria and Taiwan.4

Up until World War II, world’s fairs possessed strong symbolic importance, not just for Japan but for all great powers. They condensed the age, both in its aspirations and even in its ugliness.5 So much so that, if you were to just study these events exclusively, you would get a good understanding of the zeitgeist.

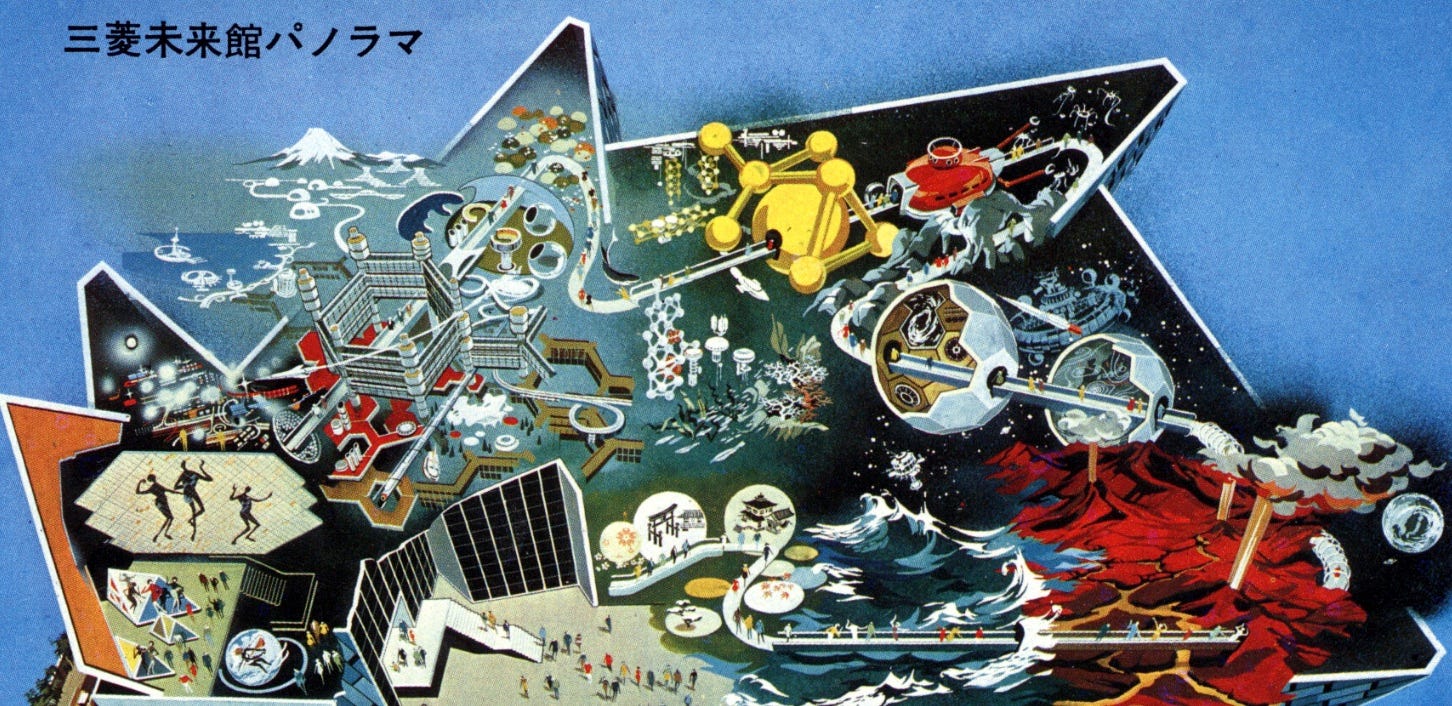

The same can’t as easily be said for later fairs. Since World War II, world’s fairs have steadily declined in their international importance. This process was gradual but became especially clear after the “crisis of confidence” of the 1970s.6 High modernism fell out of fashion, and the first world’s fair in Asia (Osaka, Japan) in 1970 also became the last one of this technologically-optimistic era. A historic low point for American-led fairs came in 1984 when the Louisiana World Exposition in New Orleans went bankrupt due to low attendance.

By the early 1990s and the Cold War now over, some began to view world’s fairs as relics of the past. The international competition that once motivated its spectacle now seemed irrelevant. Left as the sole superpower, the U.S. abolished the department responsible for them in 1998.7 Then in 2001, it withdrew entirely from the International Bureau of Expositions.8 It was a sign, as if to imply that the world had reached the end of some long historical road.

Competing Again on the World Stage

When the world starts to be perceived strategically, it is difficult to put the genie back in the bottle. Suddenly, everything appears like pieces on a chessboard, territory takes on new meaning, and ideology colors the global picture unlike before. The past few years especially have brought geopolitics and great power competition back in a big way, with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing war in Gaza, not to mention China’s rise. American-led globalization, once appearing permanent, now increasingly seems contestable.

While the new global climate may feel sudden, recent world’s fairs—or “world expos” as they’re often called now—give us some indication it was overdue. The 2010 World Expo in Shanghai, for example, was the largest ever, despite barely even registering with the American public. It was a major state-building exercise for China, largely aimed at convincing its own citizens of their rising status. Yet, the U.S. contribution was a pavilion that resembled a “low-end shopping mall” outsourced to a private Canadian firm.9 When asked about it, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton just blanky said, “It’s fine.”

Such detached attitudes come from a different time, when anxieties of U.S. decline were not yet politically mainstream. In a nod to these new realities, the U.S. reentered the International Bureau of Expositions in 2017 after a 16-year absence. It also established an “Expo Unit” in the State Department. In recent memory, expositions have increasingly been hosted outside the West. The first one in Central Asia was in Astana, Kazakhstan in 2017. Then in 2021, after a year's delay due to COVID-19, Dubai held the first world’s fair in a Muslim-majority country.

The next exposition is slated to take place in 2025 in Osaka, Japan, beating out competition from Azerbaijan and Russia. However, the event has taken on symbolic importance for an unexpected reason by speaking to issues within Japanese society. It’s been met with low public enthusiasm due to poor planning, lack of workers, untenable deficit spending, and general sluggishness in the post-COVID recovery.10 There’s now uncertainty over whether it will even take place at all.

The same can’t be said for the fair set for 2030. A few weeks ago, Saudi Arabia won the much-contested vote in a landslide victory. The Saudi state aggressively pursued an internal marketing campaign, relying on lavish dinners and even star power like Christiano Ronaldo, to win over voters. In what’s been called a “purely transactional” affair by the Italian delegation—who themselves hoped to use the event to revitalize their troubled capital—the Saudis ended up securing the surprise super-majority in just the first round. The 2030 World Expo could be the most extravagant one yet.

A New Saudi Arabia for 2030

With Saudi Arabia now securing World Expo 2030, the year is being promoted by the kingdom as a “national and global milestone.”11 Many different facets of Saudi development are crystallizing into this radical new turn. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman hopes to redeem the country’s reputation after the state-sanctioned assassination of Jamal Khashoggi in 2018—and the plan is to recreate Saudi Arabia into a tourist mega-hub and finally move beyond oil dependency. This new posture also involves asserting the Saudis as independent kingmakers, a calculation that’s behind the recent surprise détente with Iran and joining BRICS. The changes have transformed their society with Saudi citizens feeling a sense of nationalism for the first time.12

The 2030 fair aims to cross the Rubicon and make this emerging Saudi national consciousness permanent. The plan comes together in what’s called Saudi Vision 2030. Princess Haifa bint Muhammad Al Saud, the new Deputy Minister of Tourism, has said some $92 billion will be spent to remake just Riyadh in anticipation of World Expo 2030.13 The new city will effectively be the fairgrounds itself. According to state estimates, the kingdom claims some 40 million attendees will be present alongside a virtual “metaverse” component that aims to attract 1 billion visits.14

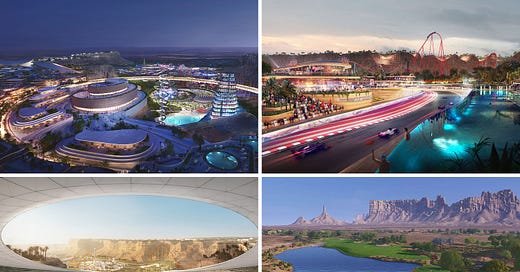

Such promises may sound hyperbolic at best, and maybe even outright false advertising at worst. But the kingdom now traffics in dreams with the construction of mega-projects like The Line—a tall but incredibly narrow 110-mile-long “smart city”—and Mukaab, the largest cube-shaped skyscraper ever, fit with holographic projections for a “mixed-reality experience.”15 Such grand dreams proliferate through the kingdom’s burgeoning entertainment sector, organized by the relatively new General Entertainment Authority. Even esports and gaming will boast their own district in Qiddiya, the first city exclusively for entertainment with the motto “Play Life.”16 It is expected to be completed by 2030.

The funds for these seemingly endless mega-projects come from the kingdom’s Public Investment Fund Program, possibly the most secretive black box of money in the world. Now firmly under the personal control of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the $775 billion fund has entangled itself in global soft power by acquiring media, sports teams, infrastructure projects, and political favors. It is reasonable to suspect the fund was heavily involved in the vote for World Expo 2030. Perhaps there is much truth to the Italian delegation’s criticism that it was all a transactional affair.

The entirety of Vision 2030, culminating in the fair, is a drastic transformation for a kingdom that only opened its doors to non-religious tourism in 2019. One has to wonder how such an unprecedented top-down reimagining will affect its society long term once the dust settles.

Selling Dreams

Earlier this year, I published a piece on the 1939 World’s Fair in New York as an event unlike any other, one that especially tapped into the selling of dreams.

As I talked about, those dreams would ultimately make modern America. The man chiefly responsible for its organization was Edward Bernays, famous for inventing public relations and bringing psychoanalytic theories to the United States. “Other fairs were interesting, entertaining, exciting…” he told an audience in 1937, “but only this one will answer the question, what does all this mean to me?”17

Some 90 years later, it does seem like Saudi Arabia is tapping into that same Bernaysian selling of dreams for their 2030 fair: an open appeal to desire through over-the-top extravagance. Even more so perhaps because unlike 1939, the 2030 World Expo plans to go deeper into the mind and its wants with virtual immersion. As the promotional video for the Mukaab states, it is about reimagining the “retail experience.”

Similar to how the 1939 World’s Fair defined modern America, so, too, could the one in 2030 define a new Saudi society. Other states will surely be watching, and they won’t be doing so idly. Historically, world’s fairs have been used to nation-build and project power on the world stage. Now that a global middle class is emerging for the first time, and non-Western powers are rising, such dreams certainly have a more eager audience than before.

If you’re interested in this topic further, I have published other essays on world’s fairs and geopolitics that might be worth reading.

Olive Checkland. Japan and Britain After 1859: Creating Cultural Bridges, pg. 17

Being “stuck in the past” was said pejoratively by Westerners of China then. Imperial Japan often contrasted its modernization efforts with China.

Japan and Britain After 1859: Creating Cultural Bridges, pg. 18.

The 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, United States, which is especially remembered today for its colonial presentations, featured Imperial Japan’s special exhibit on Taiwan (then called Formosa). At the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago, Japan used the opportunity to showcase its administration over Manchuria with events sponsored by the South Manchuria Railway Company.

The turn of the 20th century saw world’s fairs take a disturbing turn. Amid the age of high imperialism, colonized peoples were often presented as objects on the fairgrounds like in Paris (1900), Marseilles (1907), and elsewhere.

Photographer Jade Doskow has documented the leftovers of world’s fairs and the decline of optimism through her project Lost Utopias, which was made into a film in 2021.

The United States Information Agency had many functions, mainly designed to “manage perceptions” about the United States during the Cold War and non-stop thrash its communist enemies. But it was also responsible for organizing U.S. pavilions at world expositions. In 1998, a law was signed abolishing it.

In 2001, George W. Bush let the membership retainer of $25,000 per year expire citing “budgetary issues.”

Quote taken from “What Happened to the World's Fair?” in Architect Magazine.

Quoted from the official Saudi World Expo 2030 website.

Islamic identity has historically been dominant in Saudi society, but the recent reinvigoration of nationalism is a new turn led by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. “Proud to be Saudi” is the new mantra in media and political culture, rather than religious adherence. The kingdom’s Founding Day was only recently instituted as a holiday in 2022.

This hard-to-believe estimate is taken from the promotional website for Saudi Arabia’s Expo 2030. Hopefully, the metaverse then is a step up from the first virtual celebration of Saudi National Day in 2022.

Mukaab has been described as the "new face of Riyadh” and will be "one of the largest built structures in the world.” Augmented/virtual reality is a key feature of its design.

The “world’s first esports district” was announced just a few days ago as part of Qiddiya, a city entirely devoted to entertainment.

Since my University is quite close to Calatrava's Sail (visible out the windows), it often gets brought up in our daily lectures. Just after Riyadh's victory one of our professors described the situation perfectly. He essentially said Romans can cry all we want, and accuse Tunisia and Albania of betrayal, but the fact is that AS Roma's new main jersey sponsor is Riyadh Air. A company that has yet to operate a single flight. A hard-hitting reality for some.

You missed a major point for the existence of world's fairs which was to cover up the existence of, in North America at least, an advanced culture whose legacy outshone the won seeking to erase and replace it. And erase they did, destroying many preexisting structures at the end of the fairs. So much lying and intentional deceit, I'm surprised this never crossed your desk....well worth a further look.