A World of Civilization States

Seeing an opening, some states are trying to reorganize global affairs by claiming civilizational blocs of influence.

If asked to give one defining feature of the past few decades, you would likely say something related to globalization.

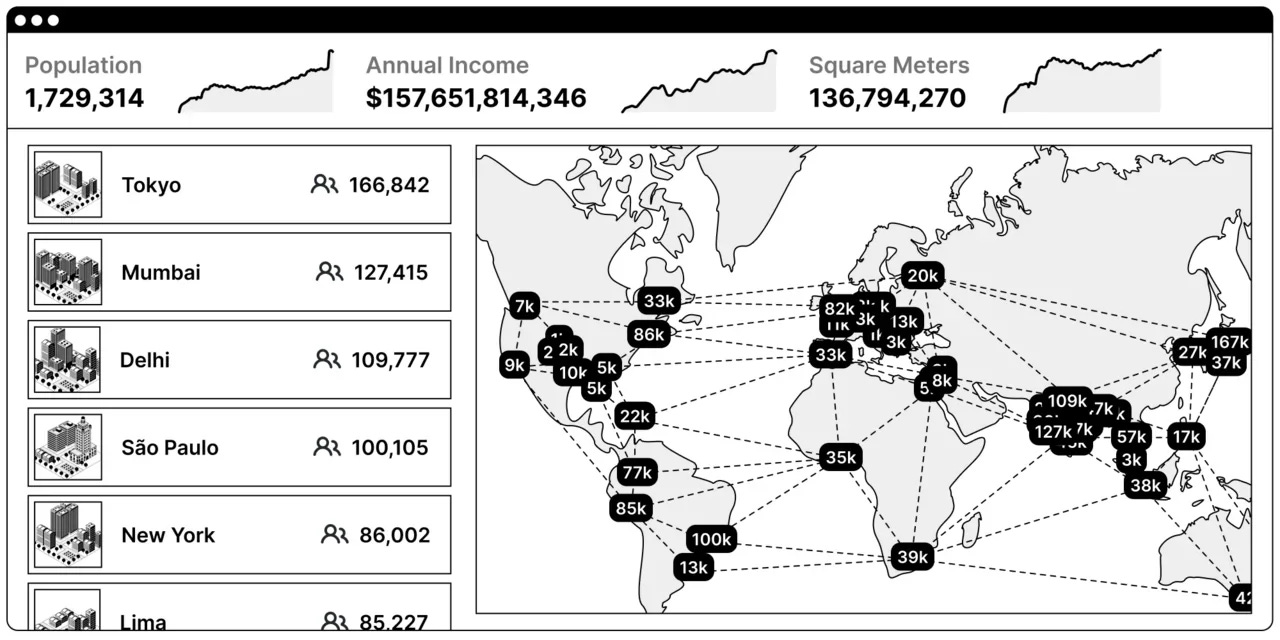

Globalization loosely includes the many processes involved in making the world a more interdependent whole. This whole has many connecting cables. One such cable is the creation of a global web of communication through the internet. Another is the expansion of worldwide trade and the linkages between national economies. Still another is the ease of travel and transport. It has affected how we think of ourselves collectively in relation to the planet. Although there have been previous eras of globalization, none compare in scope or intensity to the past few decades.

Although often praised in the abstract, globalization as we know it emerged under particular historical circumstances which define its development. Liberal capitalism triumphed as the United States became the world’s sole superpower. Globalization is therefore defined by the ascendency of Pax Americana. It is these historical circumstances that really stir contention because they determine the direction and shape of globalization.

The current global arrangement has many detractors—from the disaffected, to the have-nots, to the invisible and forgotten, entangled in a web of economic dependencies. Globalization’s losers make up a large share of the world’s population and nowadays also reside in the global core. Yet, for its advocates, this was the historical bargain. It was often said that these deep-seated cultural and economic inequalities would lessen as time went on. Despite structural shortcomings, globalization was repeatedly assumed to be both inevitable and permanent.1

So, imagine the surprise when economic leaders began publicly stating that the music had finally stopped and that the inevitable was now no longer certain. As Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, told shareholders this past March, “the Russian invasion of Ukraine has put an end to the globalization we have experienced over the last three decades.” Leading financier Howard Marks similarly informed readers at Oaktree Capital that the pendulum was swinging away from globalization toward localism. Billionaire Ken Moelis later confirmed to Bloomberg in July that ‘deglobalization’ was now certain. The outflows have already begun, with emerging economies seeing money fleeing back to the core in the past year amid a time of already-anemic foreign investment.

There’s so much more that can be said, but I bring up a few of these opinions within finance capital for a reason. It is global finance, much like a nervous system, that tells the whole economic body how to communicate with its disparate parts and where to exert its energies. So, we can take these indicators to mean, in simple terms, that the global whole is becoming more severed and segmented.

The situation is still unfolding and globalization may return. Some argue globalization is not declining at all but merely changing shape. But still, what is now certain is that the preponderance toward its inevitability was entirely misguided. Future historians and writers will likely have to unpack how the past 30 years of globalization so often produced such unscrupulous takes from commentators. So sure were they that we were at the end of some long historical road.2 This is partly because the Cold War's end was such a surprise. The feeling of having unexpectedly triumphed over a long, all-out global contest created many prisoners of the moment which persisted for decades.3

This Is Not a Cold War 2.0

While geopolitics and great state competition may be staging a comeback, they don’t look like they once did. If we think back to the past century, it was dominated by ideologies that considered themselves universal: American globalism, wrapped in freedom and democracy, and Sovietism with its ideological roots in Marxist internationalism. Both the United States and the Soviet Union spoke of their ideology as needing to span the entire world, in a grand struggle whose success could only come at the expense of the other.

We are no longer living in a world caught in between an existential battle of two universals. Only the American-led Western world is preaching universalism now. Much of the rest, embracing their own particulars and regionalisms, is trying to differentiate themselves from the Pax Americana whole. Cultural politics and civilizational claims are making a comeback as a means to conduct geopolitics. Alliances have formed, not on “shared values,” but to strategically counter American-led globalization. The breakout of the Russo-Ukrainian War has proved to be the first act of the segmentation of the world into blocs. What was previously just a possibility now must be assessed on the question of whether it can even be repaired.

While civilizational thinking in itself is nothing new, the current dynamic is of a different kind. It is being advanced as the basis for a global restructuring that will decenter Western hegemony. This new development has been given a name: the civilization state.

In this post, I will discuss the leading states employing civilizational language to stake their spheres of influence. Perhaps it will shed some light on where the future pieces may fall in global affairs. I will begin with a brief historical overview of ‘civilization’ as it emerged as an idea, and then profile four states pursuing civilizational aims today.

What’s a ‘Civilization,’ Anyway?

‘Civilization’ is a loaded and often vague term. Today, it denotes something culturally specific to a people and territory, often caught up in the imagination of who’s talking about it. However, the word was initially intended as a universalist concept.

Coined by French Enlightenment writers during the 1760s, civilization first meant a "level of perfection of a society."4 Identifiable with the progress of reason, civilization was intended to imply the highest stage of human development, the so-called "destiny of [all of] humanity."5 The French Revolution later saw itself as the cradle of this new civilization, aligning itself with universalism and natural law from which liberal rights emerged. Other contemporaries, like Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), put forward a universalism that argued, "all rational beings are members in a single moral community."6 This original idea of universalist civilization found its most immediate expression among the 'men of letters’ at the time, whose community was not bound by nation or creed.7

But throughout the course of the long 19th century, this original universalist definition of civilization became muddled entirely. Criticisms were largely incubated in German academia, producing ideas like kulturnation, volk, and the professionalization of national history writing. These concepts spread throughout Europe and beyond. The term “civilization” itself became maligned, sometimes grouped with empire and imperialism, and France began to describe its colonial ambitions as “civilizing missions.” As the 19th century went on, “civilization” had less to do with universalism, but instead became a means through which Europe separated itself from the rest of the world.

As immensely consequential as these developments were, it was actually outside of Western Europe that the idea of “civilization” took on new life. For the first time, it was applied as a model for understanding the supposed cycles of history.

A Civilizational Theory of History Develops for the First Time in 19th-Century Russia

An entirely different understanding of "civilization" emerged in Imperial Russia, on the periphery of modern Europe. Nikolay Danilevsky (1822-1885) is credited with being the first thinker to assign historical-cultural types to a philosophy of history.8 Danilevsky used civilizational models to 'scientifically' explain how cultures rise and fall.

Danilevsky was, first and foremost, a naturalist who specialized in the classification of living things like insects and plants. Like in nature, Danilevsky viewed historical-cultural types as having lifespans similar to organisms.9 And, like organisms in nature, they were in competition and often replaced one another. Each historical-cultural type was thought to spawn a civilization, each defined by five major factors: language, political independence, noninheritability, path toward completeness, and its stages of life.10 In Russia and Europe (1869), he outlined 10 major historical-cultural types that have gone through this civilizational process including Indian, Iranian, Greek, Germanic-Roman, Chinese, Egyptian, and others.11 He posited Slavic and American as two of the newer cultural-historical types.12

Danilevsky viewed Western universalism as a dangerous abstraction that was an "unconscious identification of Europe with the history of mankind."13 For Danilevsky, the world is not a linear process toward a universal whole but made up of independent civilizations who rise and fall cyclically. There is no comparative hierarchy of development either, no ideal end-point for the entire world. Each historical-cultural type is said to create its own destiny.

The starting point of Danilevsky’s theory is a rejection of the historical process as a single evolutionary flow that unites all countries and peoples of the world.14

Danilevsky's ideas could have easily fallen into the dustbin of history and been forever forgotten. Instead, they've been resurrected: this once-obscure 19th-century figure has now risen to become one of the most cited thinkers in Russian international relations and beyond.15

In some sense, all civilization states are effectively in conversation with Danilevsky’s work, whether they know it or not.

Civilizational Narratives Have Their Moment

In the decades after Danilevsky’s death, civilizational history writing reached its height and became something of a trope during the first half of the 20th century. The world wars produced some soul-searching among Europe’s intelligentsia, who wondered whether they were on the decline as a civilization.

Some 50 years after Danilevsky, Oswald Spengler (1880-1936) published The Decline of the West (1918) which prefigured itself along similar historical-cultural types. His contemporary, Polish historian Feliks Koneczny (1862-1949), also developed a parallel system of 'comparative science' for civilizations. Even well up to the 1960s, civilizational history remained a popular genre because it allowed one to write a 'history of everything.'16 For example, The Story of Civilization (1935 - 1975), compiled over decades by Will and Ariel Durant, was a longtime top seller. But starting from the 1970s, the once-popular genre of epic civilizational histories rapidly declined with the exception of Samuel P. Huntington’s notorious and much-discussed Clash of Civilizations (1996). Outside of archaeology, talk of “civilizations” feels a bit outdated today for many Western academic writers and their audiences.

Why recount these details of history writing?—I mention this all because, with the exception of Danilevsky maybe, these writers of civilizations were all Western or Western-adjacent. They told grand stories spanning millennia and almost always described something other than themselves. Today’s civilizational arguments, on the other hand, are being put forward by their very own subjects and the states said to represent them. Civilizational identities that counter Western power have finally become real and consequential because of the “rise of the rest.”

The Lay of the Land: A Few of the Rising Civilizational Claims

What is a civilization state?—A civilization state is a state that claims to represent a multicultural and multinational region said to be unified by a common value system and/or language. Such a state often legitimizes itself by claiming to be the successor of institutions and ways of being from the ancient past. According to this outlook, the world is made up of many civilizations which each have their own center. Such an arrangement is inherently multipolar, without clear boundaries, and with many great powers present (and who respect each other, allegedly).

The civilization state concept is not about dividing the world between Western and non-Western. It is also not about some simplistic "clash of civilizations" narrative, either. In simplest terms, it is about describing a world where the West is no longer exclusively dominant.17 A multipolar, civilizational world order will also likely conflict with the nation-state model, which first developed in Europe and later became the international standard. Our present situation can be viewed as an interregnum period, a time of many unknowns over what the new consensus may be.

Still, it is not like such civilizational politics is alien to Europe or the United States, either. The West's very rise was rooted in its own civilizational awareness and European identity.18 The European Union has become something of a civilization state for others to model, despite rarely describing itself in those terms. The United States, too, has commonly seen itself as the “shining city on a hill” with its own value system and belief in its exceptionalism. The Monroe Doctrine is still evoked to claim both of the Americas as the U.S. sphere of influence. The civilization state is therefore not a new historical concept at all. Both the United States and European Union already fit the definition of one, despite not speaking its language explicitly any longer. Non-Western civilization states, therefore, see themselves as simply aspiring to a supranational form already represented in practice by the European Union and the United States.

The appeal of civilizational claims is that it provides states with easy justification when forming geopolitical blocs. They are inherently political constructions in the service of power, and are therefore laden with contradictions and ambiguities. In a competitive environment of global capitalism and its diminishing resources , disputes over its boundaries are possible and even likely. A multipolar world of civilization states is a world that privileges vast scale. Smaller states will be indirectly pressured to find their orbit by joining blocs via unions and confederations for economic benefit. In this sense, the European Union was something of a trailblazer. These developments will also have the unfortunate effect of rendering many actual people on each region’s periphery invisible.

While I am not optimistic, all this must nonetheless be grasped with some degree of realism. Part of that realism involves understanding how states are going about constructing their own civilizational identities.

I have chosen four states to profile who together make up just under half of the world’s population: Turkey, Russia, China, and India.

Turkey

In June 2022, Turkey formally requested the United Nations to change its name. The new name, first proposed by President Erdogan last year, would be Türkiye. The change “expresses the culture, civilization, and values of the Turkish nation in the best way," read the communique given out to several international bodies.

The move may seem minor, but it is part of a long string of changes that seek to transition Turkey from a Western-oriented and secular nation-state into an autonomous, regional power-broker under a civilizational moniker.19 These developments have all taken place under the dominant Justice and Development Party (JDP) and its President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Altogether, this pivot began with talks of a "New Turkey" in 2014, the year when President Erdogan told the UN General Assembly, "the world is bigger than five" and "the West is no longer the only center of the world."20

Ahmet Davutoglu is often credited with being the intellectual behind Turkey's civilizational pivot. He argues that civilization is not an identity, which he considers superficial, but instead a "historical institution."21 Civilizations are rooted in how one perceives oneself: it is an ontological and geographical position from which greater forms—cities, states, and the world order—are constructed. For Davutoglu, "geography can only turn into a meaningful World through civilizational belongingness… [which develops] from self-perceptions."22 A multipolar world of many self-perceived civilizations is considered by Davutoglu to be the "final stage of the world order."23

Despite Davutoglu having a complete falling out with Erdogan in the past few years, this civilizational idea continues to inform Turkey's international orientation. One direct consequence is that Turkey views the West as neighbors instead of 'one of us.' This is a sharp departure from Mustafa Kemal, the founder of the Turkish Republic, who considered Western civilization to be a universal ideal.24 Rejection of Western universalism has allowed Turkey to position itself as an anti-hegemonic "dark horse" and middle-power mediator, evident by its ambiguous and opportunistic behavior during the Russo-Ukrainian War.25

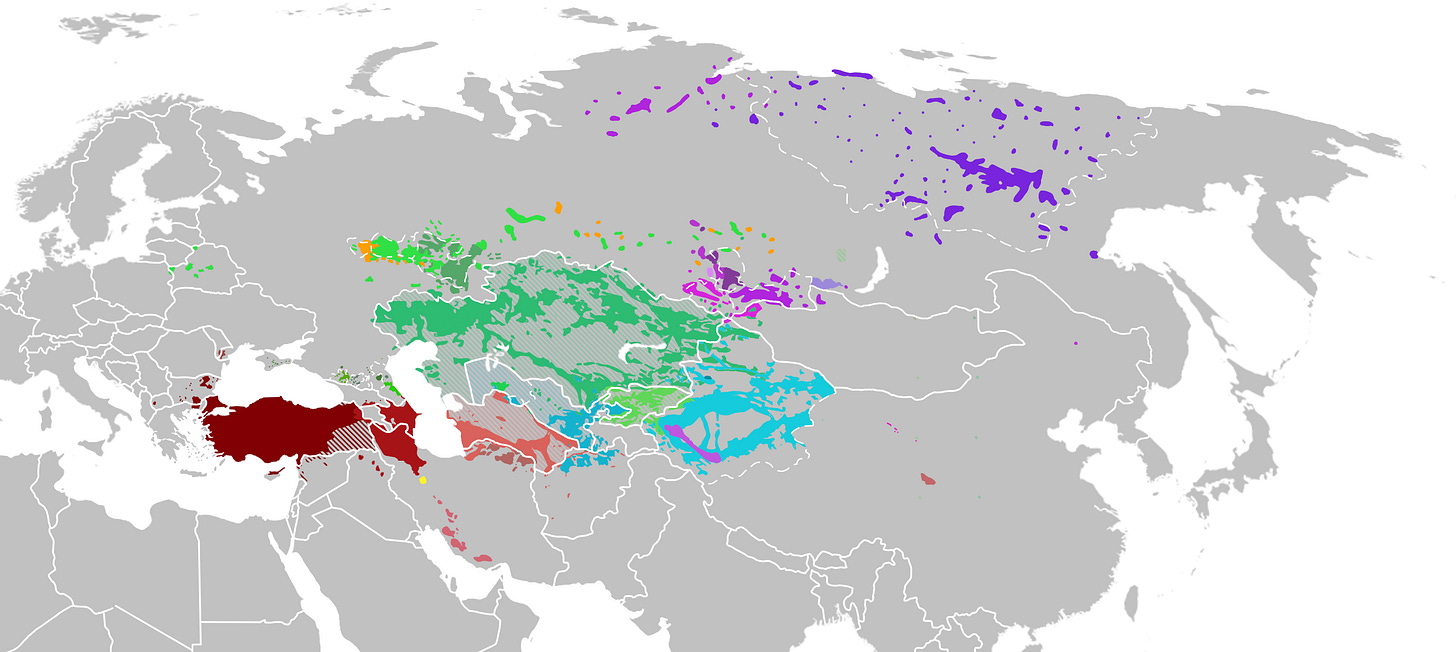

The real fruits of Turkey's civilizational pivot have been in Central Asia where it has tried to carve influence in the post-Soviet sphere. As Erdogan declared in Baku, Azerbaijan at the 2019 Organization of Turkic States, "we will be most powerful as six states, one nation."26 Turkey's civilizational politics in Central Asia centers on Pan-Turkism, as it tries to court Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan into its orbit. Although the organization began as a cultural alliance, it has since been deepened into a political-economic union for trade and energy. The idea of a proper "Turkic Union" to rival the European Union has been floated.27 Middle-school textbooks across these states commonly now boast of a common Turkic history.28

Turkey's civilizational pivot remains multifaceted, however. The state leverages cultural ties and history where it finds them most useful. While it may overplay Pan-Turkism in Central Asia, it tries to forge linkages on other grounds elsewhere—be it via Islamic links in the Middle East and the Balkans, or by positioning itself as a 'Mediterranean power.' It narrativizes a civilizational story as a way to affirm its cultural and political autonomy against the perceived encroachment of Westernization. Through this strategy, the Turkish state believes a new order can be constructed that is more in its favor. "I am a defender of an alliance of civilizations," Erdogan stated in 2017, for "the world is bigger than five is the outcry of civilization."29

Russia

In March, I published an article titled The 19th Century Returns where I unpacked Vladimir Putin’s frame for invading Ukraine. I paid particular attention to an essay titled On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians (2021), written by Putin himself, which struck me as a document whose parts could have been written some 150 years ago. The document is primarily about the Russian national question as it pertains to Ukraine, but it is also rooted in a civilizational concept known as the Russian World.

In 2018, Putin addressed the 25th anniversary of the World Russian People’s Council to facilitate, according to the Kremlin, "civilizational development." Putin's speech directly references Danilevsky's writings whose work I explored earlier in this piece. "No civilization can call itself supreme," Putin stated, "together India, China, Western Europe, America and […] others" provide the "foundation for building a multipolar world."30

In the past decade, Putin and other formulators of Russian state policy have increasingly played up their civilizational uniqueness rooted in Orthodoxy, culture, shared history, and references to the "Russian soul." Nonetheless, this understanding is multiethnic and does not only include Russians.31 As the Eurasianist Lev Gumilyo (1912-1992) wrote, the Russians and Central Asian peoples were bound together in what he termed a "super ethnos."32 Putin has been careful to affirm this multiculturalism as long as it is within Russia's sphere. This civilizational posture is closely aligned with Eurasia: Russia is said to be neither East nor West but uniquely its own space, as a kind of mediator of two worlds.

Out of all the possible civilization-states, Russia remains the most apocalyptic and totalizing in its understanding of history’s direction. It reminds me of what Pyotr Chaadayev (1794-1856) despairingly wrote of Russia in 1836:

We are an exception among people. We belong to those who are not an integral part of humanity, but exist only to teach the world some type of great lesson.33

As if in conversation with this often-cited passage, Russia seems to have taken up a world-historical mission for itself yet again to ‘teach the world a lesson.’ It has become the most aggressive in its opposition to Western universalism, which goes by many names. The Western-led world has been called “Atlanticism," its project one of 'globalism' and its leader, the United States, as an “Empire of Lies.” In July 2022, Putin spoke of the “golden billion” to describe the topmost seventh of the world's population whose way of life is said to be only possible from the ‘exploitation of the rest.’

Russia's civilizational understanding is therefore fundamentally apocalyptic: it foresees a potential all-out conflict between itself and the Atlanticist elite of the golden billion, over a dwindling global pool of resources that mainly resides in Russia. As Putin stated in his call for a partial mobilization against Ukraine on September 21, 2022, “the purpose of the West is to weaken, divide and ultimately destroy our country.” The idea that the U.S. wants to “carve up” Russia and break it apart for resources remains the prevailing view among Russia’s civilizational and national ideologues.

Today, all three of the most-cited scholars in Russian international relations fall into the "civilizational conservatism" category, and it has become institutionalized.34 Russia has ascribed to itself not only civilizational values, but an entire historical end-point or telos: it is first destined to put together a "coalition of the dissatisfied," then elevate 'the rest' to be on par with the West, and finally reorganize the international order under multipolarity and inter-civilizational cooperation. This has been likened by its advocates to Russia's historical mission.

As Putinite ideologue Alexander Panarin writes, it is Russia's role to make it "possible for humanity as a whole to advance into the future not by way of cultural disarmament and depersonalization, but by preserving mankind's cultural-civilizational diversity."35

China

China has been called the original civilization state. This is because it has more or less existed as a polity for over 2000 years. This long history dominates how the Chinese state views itself in relation to the world. It has been argued that China is only nominally a nation-state because it exists in an international order not of its choosing.36 For President Xi and his contemporaries in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), socialism with Chinese characteristics represents the end-point of a millennia-long civilizational process.

The term “civilization” (文明; Wenming) first entered the party discourse around the 1990s as part of its project of a 'socialist harmonious society.'37 Expanding this cultural project is the task of the Central Guidance Commission on Building Spiritual Civilization, formed in 1997. It is currently chaired by Wang Huning who is considered to be the leading intellectual in the CCP. Huning's writings stress the need to create new value systems to undo the atomizing effects of modernization. As he argued in 1993, "while Western modern civilization can bring material prosperity, it doesn't necessarily lead to improvement in character."38 It was these words, noticed by then General Sectary Jiang Zemin, which granted him entry to the upper echelons of power. Huning can be called an ideologue in the purest sense of the word because he believes in the independent power of ideology and culture. In his view, "strong states are culturally unified states."39

The construction of a “spiritual civilization” with homogenous values is thus seen as necessary for the Party's political survival. In lieu of this imperative, China has taken an overbearing role in socially engineering its society to align it with ‘Core Socialist Values,' first promulgated in 2012. It has also pursued historical research to deepen its civilizational history via the National Research Project on Tracing the Origins of Chinese Civilization (中华文明探源工程), which involved some 400 scholars and 70 universities.40 One of President Xi's foreign policy goals is the dialogue between civilizations, indicating that he views them as a relevant category of international diplomacy.41

But why?—why does China, unlike other states, place such an outsized priority on values and ideology for its political governance? Even among other possible civilization states, it is peculiar. This is because it is fundamentally a reaction to the collapse of the USSR. As economist Branko Milanovic explored in a brilliant post titled The Rule of Nihilists, President Xi views the Soviet collapse as a result of “ideological nihilism.” He said so plainly in his 2013 speech to the members of the Central Committee of CCP. As Milanovic writes:

Once the party loses the control of the ideology, Xi argues, once it fails to provide a satisfactory explanation for its own rule, objectives and purposes, it dissolves into a party of loosely connected individuals linked only by personal goals of enrichment and power.

China’s civilizational project and emphasis on values should therefore be interpreted as a reaction to the collapse of the USSR. It is a means to explain its own rule and not suffer the same fate. Moreover, the codification of civilizational discourse within the CCP’s ideology started to take hold after the end of the USSR.

In light of this relationship, the logic behind the CCP’s actions takes on new meaning: it is politics in the service of cultural unity to strengthen political power. The alternative is ideological nihilism and collapse. The CCP, therefore, views the stakes as existential. This is why China goes to such great lengths, oftentimes excessively, to assert its claim over Taiwan; it has attempted to culturally assimilate the Uyghurs; and it remains the last country to maintain strict zero-covid lockdowns. These priorities, among others, make clear that any discrepancy or rogue element within its narrative is viewed as undermining political authority itself. Extreme measures are therefore taken to correct them.

Altogether, this makes for a categorical difference. Whereas the Russian civilizational project primarily fears outward threats to its territory, China’s project instead fears what is internal: the disintegration of its value system on which its political authority rests.

India

In the wake of the Russo-Ukrainian War, many have been surprised by India’s ambiguous actions. The country has adopted a position of public neutrality and has abstained from condemning the invasion in any international body. Falling out of the Western consensus, it has turned away from judging international politics through the prism of values. As one commentator for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace writes:

New Delhi views the division between democracies and autocracies over Ukraine as largely accidental: it judges the dividing lines to be drawn on the basis of national interests rather than on the character of the regimes in question.42

The Russo-Ukrainian War has given India's President Modi his first, real "multipolar moment."43

India’s neutrality has long been part of its international outlook, cultivated since its founding. During the Cold War, it was part of the Non-Aligned Movement. But being the rising power that it now is, other states are now openly vying for its affection. Naturally, such newfound status makes for some soul-searching which has intensified civilizational-cultural politics within the country. This has been used to both smooth over internal divisions and justify its separation from Western liberalism.

The current state, led by ideologies within the BJP party, claim lineage to a civilization spanning millennia, as far back as c. 1500 BC and earlier. Much like China, Indian historiography stresses its ancient past; but unlike China, the state places a greater emphasis on historical revisionism rather than values. This is because India is a post-colonial construction, an issue that has injured its self-perception and has been debated since its founding. Constructing a history for itself rooted in the ancient past is therefore a leading political focus.

In 2018, President Modi quietly appointed a new committee of scholars to rewrite the history of India. The mix of scholars included historians and archaeologists who were tasked with, among other things, finding evidence for Hindus being the direct descendants of the land's first inhabitants.44 Another goal was to prove Hindu texts are fact rather than myth. As the Chairman of the committee told Reuters, both of these objectives are needed to substantiate the thousands-year-long continuity of Indian civilization.

Historical revisionism has largely been the project of Modi's BJP party and its many ideological allies. Common are references to Hindutva, the belief in India as fundamentally a Hindu state, and opposition to Islam. The country's cultural ideologies openly criticize the secular origins of India's founding constitution. At the same time, civilizational claims often cling to the first article of this same constitution which equates India with Bharat, an ancient Hindu name for India and beyond.45 Political analyst Bruno Maçães has argued the BJP's massive victory with 303 seats in 2019 was due to Modi's affirmation of Bharat as a civilization.46

All being said, the politicization of history is always a difficult feat and prone to schisms, especially true in a state said to represent over a billion people. Arguably, India’s cultural-civilizational project remains the most fragile out of all the other examples mentioned.

Other Civilization State Candidates

I have discussed four of the leading states engaged in civilization-cultural politics. There are, of course, still others. If such groupings become the basis for geopolitics and power politics, then we should expect other states to conform to try to carve their own niche.

Two examples that have not been explored in detail are the United States and the European Union. They generally do not describe themselves in civilizational language since they are hegemonic.

Aside from them, other civilization state candidates include—Iran which is trying to leverage its cultural soft power in Central Asia; Saudi Arabia as a middle power that leads the Sunni world; the African Union if it is able to strengthen its institutions as a group; and Egypt which possesses an ancient historicity sometimes linked to its current identity.

States engaging in civilizational politics to project power must contend with some countertrends not working in their favor, however. I would like to discuss one in particular, which is the internet itself.

The Internet as a Countertrend

In June 2022, technologist and serial entrepreneur Balaji Srinivasan published a provocative book called “The Network State.”

In it, he proposes a counter-idea to the modern nation-state: a world where decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), bound by online smart contracts, attain sovereignty. They would have populations, collectively-managed income, and even territory. Rather than lawmakers, there would be code amenable by its ‘citizens’ with all bookkeeping fully transparent and future-proof: an internet community codified as an actual state.

Let me be totally frank in saying, I sincerely doubt actual states would ever allow such an idea to materialize in any real sense. Still, the book is right in seeing the internet as a loosely self-organizing, global village. Its very existence represents a universalism in itself, one that could chip away at the very boundaries civilizational states are trying to create.

The internet certainly possesses the potential to dissolve othering differences and become a universal point of reference. The civilization state’s biggest obstacle is arguably not the West, but the steady march of digital technology. The internet’s infosphere begets globalization. The percentage of the world population that is online continues to rise and now stands at 63% (over 5 billion). In some possible scenario, the internet could allow for the flourishing of a kind of new, digital humanism.

I write this, of course, with many qualifiers. Both Russia and China have carved digital spaces partly separate from the Western-led internet. India hopes to do the same. Censorship, in general, is on the rise. There is also the problem of digital infrastructure itself: how globally-oriented can the net be when its profiteers are Western monopolies? Not all users are made equal online, far from it, nor is this global village idealistically flat. By many metrics, the quality of the internet is getting worse. Overall, such a universal project would require global, antifragile, and trustless infrastructure without the potential for intermediaries to compromise it.

The internet is a completely novel variable amid this cultural-civilizational resurgence. Future-oriented technological progress is happening alongside the rise of past-oriented civilizational narratives, creating a potent mix that would have been unimaginable decades ago. What does it look like when ancient, civilizational ideas return amid a technologically runaway world? Whether this will strengthen the multipolar blocs forming or be its undoing is an open question.

Some Final Reservations about a Fool’s Cap World

I began this essay with the image of the Fool’s Cap Map of the World. Think of it, in some sense, as a summation of international affairs. “Vanity, all is vanity.” Perhaps it helps to return to this for perspective.

In my view, globalization has always been a deeply lopsided process. A crisis was bound to arise that would shake it to its core. A multipolar world is arguably a fairer world. But still, so much of recent history tells us cultural politics in the service of states rarely bode well, especially when the boundaries are so ambiguous. Civilizations are such broad concepts, one that can easily be manipulated and repurposed by states on an imperial whim. With the Russo-Ukrainian War expected to last for some time, the current segmentation of the world will likely persist and even deepen with some level of open hostility. Any starting point for mutual understanding has already been poisoned.

While I have profiled a few civilization states here from a realist perspective, it is also clear they are not of the same general type. They each have their separate drives. For Turkey, the project is largely ethnic-linguistic as part of pan-Turkism; Russia has a deep paranoia of being destroyed by the West; China prioritizes homogenous values for its political survival; And India fixates on historical revisionism.

Civilization states may form some common front against American-led globalization, but they are so dissimilar in their priorities. So much so that one cannot help but wonder what kind of consensus will arise if and when Pax Americana truly breaks down.

Although it has been discussed to death, this is essentially Francis Fukuyama’s End of History (1992) theory in a nutshell: with the defeat of communism, liberalism and its market economy was believed to have no serious ideological competition any longer.

There are plenty of examples, but Thomas Friedman comes most immediately to mind and his book The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century (2005) which won many awards.

An excellent book on this is The New Twenty Years' Crisis: A Critique of International Relations, 1999-2019 by Philip Cunliffe.

Woolf, Stuart. “French Civilization and Ethnicity in the Napoleonic Empire.” Past & Present, no. 124 (1989), pp. 96.

Jennings, Jeremy. "16. Universalism". The French Republic: history, values, debates, edited by Edward Berenson, Vincent Duclert and Christophe Prochasson, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2011, pp. 145.

Somsen, Geert J. “A History of Universalism: Conceptions of the Internationally of Science from the Enlightenment to the Cold War.” Minerva 46, no. 3 (2008), pp. 363.

Alalykin, Izvekov. “The Russian Sphinx: Contemplating Danilevsky’s Enigmatic Magnum Opus Russia and Europe.” Comparative Civilizations Review (2022), pp. 78. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2221&context=ccr

Ibid., 79.

Danylova, Tetiana. Hoian, Ihor. “Culture as a Living Organism: Some Words on Danilevsky’s Theory of Cultural-Historical Types." Path of Science 5, no. 5 (2019). pp. 2003-2004.

Ibid., 2002-2003.

Izvekov, 79.

Walicki, Andrezej. A History of Russian Thought: From the Enlightenment to Marxism. Stanford University Press (1979), pp. 295.

Danylova and Ihor, 2002.

The standout remains Arthur Toynbee’s A Study of History (1934 - 1961) which was compiled over almost three decades, documenting the rise-and-fall of 21 civilizations. Once the preeminent historian of his era, his work has largely been forgotten—a testament to how historians and writers have soured on civilizational understandings of the past for being too vague and prone to exaggerations.

Acharya, A. (2020). The Myth of the “Civilization State”: Rising Powers and the Cultural Challenge to World Order. Ethics & International Affairs, 34(2), pp. 152.

Ibid., 141.

Yesiltas, Murat. “Turkey’s Quest for a “New International Order”: The Discourse of Civilization and the Politics of Restoration.” Perceptions XIX, no. 4 (Winter 2014), pp. 43.

Ibid., 44.

Ibid., 45.

Ibid., 56.

Ibid., 66.

Egedy, Gergely. “Nation v. Civilization? The Rise of Civilizational States.” Civic Review 17 (2021): 245.

The quote is from Chaadayev’s First Philosophical Letters, cited on Wikipedia.

Ibid.

Dynon, Nicholas. "Four Civilizations" and the Evolution of Post-Mao Chinese Socialist Ideology". The China Journal. Vol. 60. pp. 83.