When Writers Became Politicians

As the Soviet Union fell apart, dissident writers in Central Europe came to power, but some had mixed feelings about their newfound purpose

In 1968, the general mood in Central Europe was deeply pessimistic. That year, the Soviet Union together with the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia to put down the reformists. Just twelve years earlier, Hungarian revolutionaries had also been subject to a bloody crackdown that claimed thousands of lives. The repression was so openly ruthless that it even disillusioned some communists.1 From the perspective of the Soviet leadership though, it was a relative success. Premier Leonid Brezhnev declared that the “triumph of the socialist system” in Czechoslovakia “can be regarded as final.”2 Still, if needed again, the “armed might of the socialist commonwealth” would ensure it remained so.3

The Brezhnev years (1964-1982) are today viewed as a time of widespread stagnation that ultimately led to the Soviet Union’s collapse. However, it was hard to imagine such a possibility in 1968 and the two decades that followed. In 1984, Hungarian dissident writer György Konrád spoke tragically of his country as being trapped in an “imperialist bargain” between West and East.4 Little seemed to lie ahead except the present forever or war.5 And to the alarm of many dissidents, the people of Central Europe were starting to adjust, and even accept, the new normal. Konrád jokingly quotes the former Hungarian Communist party boss Matyas Rakosi, who allegedly asked his officials: “Comrades, have we sunk so low as to be taken in by our own propaganda?!”6

There was always the risk that Central Europe would accept its fate. The Soviet Union had devolved into a cult of power that ruled over its people like a leviathan, but still hid its motives behind ideology. Alternative horizons were closed off and difficult to imagine, and many resigned to silence. Because there was no independent public, dissidents were uniquely called upon to imagine a new one.

These writers would go on to be elevated to the status of moral heroes and national icons. Between 1968 and the end of the Soviet Union, the underground flourished. “In the middle of our tunneling,” Konrád wrote, “we heard voices on the other side.”7 When society finally arrived at the “other side” with the Soviet Union’s collapse, these same writers were then called upon to enter politics en masse. In a rare moment, an entire literary underground came out as victors. They were now tested to act out their stories and philosophies in reality as politicians, often with contradictory results.

A Politically Hopeless Situation

Let me preface this by first bringing it to the present day. A common observation nowadays has been the decline of institutional trust and public life, particularly in the United States and other Western democracies.8 To put it differently, there has been a decline in “civil society.” It’s an important term that broadly includes everything outside of the state and for-profit enterprise.9 When it’s strong, civil society is made up of many shared interests, groups, and independent institutions that can pressure the state toward real demands. It’s arguably what gives life to any free society.

I mention this to better illustrate Central Europe’s depressed position after 1968 by way of comparison. Unlike our current predicament, writers found themselves speaking to a public defeated and virtually nonexistent in independent terms. Dissidents openly admitted the political situation was hopeless. Civil society had not only declined but had been thoroughly crushed by the state. The cold bureaucracy instilled in people a doomed feeling this was permanent. As playwright and future Czech President Václav Havel wrote in 1987, “the bureaucratic regulation of the everyday details of people’s lives is another indirect instrument of nihilism.”10

It is here that public matters infiltrate private life in a way that is very “ordinary,” but extremely persistent.

The sheer number of small pressures that we are subjected to every day is more important than it may seem at first because it encloses the space in which we are condemned to breathe — and there is very little air in that space.11

Havel characterized the Soviet system of the 1970s and ‘80s as “post-totalitarian.” Its rule over Central Europe was not a classic military dictatorship by any means. Post-totalitarian systems derive their legitimacy, not from individual personalities, but from history. The Soviet Union claimed the popular workers’ movements of the past and inherited the moral legacy of the anti-fascist struggle.12 It also justified itself through a universalist ideology that sought global appeal. According to Havel, such systems are never improvised: they are comprehensive in their laws and regulations. Rather than enslave, they seek to make their subjects feel rational by providing them with an all-explaining worldview. The priorities and procedures are out in the open, and state officials carry out their tasks like automatons. “Individuals need not believe all [the government’s] mystification,” Havel writes, “but they must behave as though they did or tolerate them in silence.”13

Giving Up on Politics

After the repression of 1968, it became clear things were unreformable. Because the state had such a grip on public life, many felt there was no emancipatory potential in politics. “What is to be done when nothing can be done?” rhetorically asked Polish dissident Jacek Kuroń.14 After 1968, the opposition gave up on attempting to democratize the state and instead asked how life should be lived and shared with others. If politics was hopeless, perhaps the focus should be on civil society and making it independent.

From this breakthrough emerged a counter-movement which György Konrád aptly called “antipolitics.” To use the language of Havel, engaging in politics trapped one in the suffocating web of post-totalitarianism which provided “very little air.” The solution simply could not be one where “people are organized, so they may then allegedly be liberated.”15 Captive minds would just end up recreating the same conditions. As Havel famously wrote in The Power of the Powerless (1979), hope lay instead in each individual pursuing an ethical life. These individuals could then presumably come together to form a new civil society that could breathe again. Havel coined its credo as “living in truth.”16 Polish journalist Konstanty Gebert imagined living in truth as setting up a “small, portable barricade between me and silence, submission, humiliation, shame…” 17 The idea was to make people’s inner core untouchable by the alienation creeping outside.

In his 1984 speech “Politics and Conscience,” Havel spoke directly on antipolitics and how he related it to inner truth.

I favor “antipolitical politics,” that is, politics not as the technology of power and manipulation, of cybernetic rule over humans or as the art of the utilitarian, but politics as one of the ways of seeking and achieving meaningful lives, of protecting them and serving them. I favor politics as practical morality, as service to the truth, as essentially human and humanly measured care for our fellow humans. It is, I presume, an approach which, in this world, is extremely impractical and difficult to apply in daily life. Still, I know no better alternative.

One such fundamental experience, that which I called ‘anti-political politics’, is possible and can be effective, even though by its very nature it cannot calculate its effect beforehand. That effect, to be sure, is of a wholly different nature from what the West considers political success. It is hidden, indirect, long term and hard to measure; often it exists only in the invisible realm of social consciousness…

Yes, “antipolitical politics” is possible. Politics from below. Politics of man, not of the apparatus. Politics growing from the heart, not from a thesis. It is not an accident that this hopeful experience has to be lived just here, on this grim battlement… We have to descend to the very bottom of a well before we can see the stars.18

According to the Central European dissidents, civil society was to be neither apolitical nor beyond politics, but anti-political.19 Society had been captured by the state. To make itself autonomous, it had to be against institutional politics, or else it risked being co-opted and exploited by post-totalitarian control. For these dissidents, antipolitics was not just some strategy to topple Soviet rule, but an entire worldview. And to Western outsiders, it forced questions about civil society that many today still take for granted.20

As a shared endeavor, antipolitics took on many surprising forms. The movement Solidarity, which would be chiefly responsible for toppling Soviet rule in Poland, always claimed its activities were social (podmiotowość), not political.21 In one notable clash in 1980, striking workers in Gdańsk collectively told the state committee that “politics is your business, not ours.”22 Despite strict martial law being introduced as a response in December of 1981, the ideas quickly spread. As Polish writer Adam Michnik wrote in Letters from Prison, “for the first time of communist rule in Poland… ‘civil society’ was being restored.”23 The Solidarity movement spoke of civil society as an exciting new place to be discovered. “We don’t need to define it. We see it and feel it,” said Solidarity’s parliamentary leader Bronislaw Geremek in 1989.24 It’s as if Geremek was echoing what Havel said — that the task of building civil society was “hidden, indirect, long term and hard to measure… it exists only in the invisible realm of social consciousness.”25 Dissidents genuinely did not know what they’d find.

These developments and their vague demands irritated party officials, who in one instance mockingly addressed the movement as “His Excellency, Civil Society.”26 In their frame of mind, they could not understand the desire for an autonomous public and viewed it as delusional hubris.

Creating a “Second Culture”

In the words of Czech poet Ivan Martin Jirous, one of the goals of the antipolitics movement was to create a “second culture.”27 Fellow Czech writer Václav Benda similarly called for building a “parallel polis” in his banned 1977 essay.28 Society had to organically develop from below, separate from the state. Both of these concepts would be deeply influential to Havel’s understanding of giving “power to the powerless.” The turn toward civil society, rather than politics, also greatly elevated those who created culture, namely writers and artists.

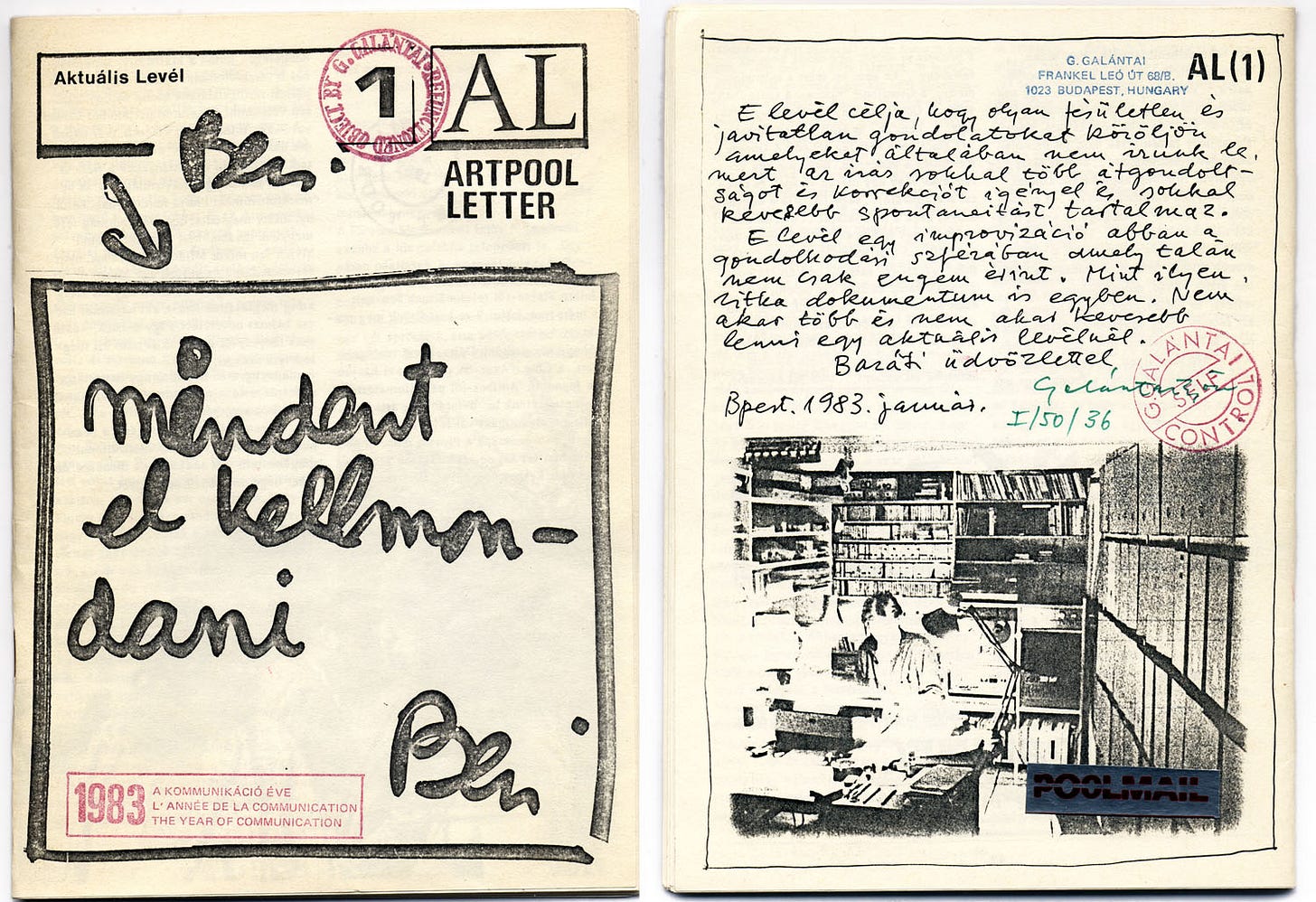

Through novels, films, poetry, music, and other mediums, dissidents explored the extreme conditions of life in “Other Europe.”29 The underground following was devout, and it was easy to completely absorb oneself in reading then. “The word was the most valuable thing”, recalled Jan Šicha, who spent all his factory pay on it.30 According to Czech writer Jáchym Topol, the 1970s and ‘80s were a time of “manic reading of books.”31 Many of the period’s canonical texts were distributed as clandestine literature (samizdat).

Novels of the samizdat period often dealt with life on the edge of dehumanization. One common theme concerned the terrifying that had become mundane. György Konrád’s The Case Worker (1969) follows the life of a social worker whose life has been made exceedingly difficult by the country’s suicide rate, allegedly then the highest in the world.32 The Guinea Pigs (1970) by Ludvík Vaculík tells the first-person story of a bank teller desperate to be “in control” of something for once, who adopts and experiments on guinea pigs for morally questionable reasons. In Ivan Klima’s Love and Garbage (1986), a dissident writer takes up the job of street sweeper and begins a relationship that forces some difficult choices.33 In fact, many dissidents did take such menial and low-pay jobs during the late Soviet era, as they were banned from better-paid professions.

Other novels focused on anti-utopian themes with brute realism. One particularly famous samizdat novel of the underground was Invalidní sourozenci (“The Invalid Siblings”, 1974) by Egon Bondy.34 Set in the year 2600, the dystopian sci-fi story follows those deemed useless to totalitarianism living in ghettos amid widespread ecological decline. Pungent garbage, accumulated over generations and generations, surrounds the living quarters of those deemed unfit as they converse and live their lives. The novel would become a bible of sorts for the Czech underground.

Still others explored themes of individuality, memory, and authenticity amid absurd conditions. There was often an element of the semi-autobiographical present, as a way of fighting back against the state’s single-minded narratives.35 Havel himself started as an absurdist playwright whose works satirized the bureaucracy.36 Milan Kundra’s The Joke (1967) is about a student’s politically charged prank that somehow completely derails his life. Kundra’s most famous work The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984) is a moving panorama of private lives in the aftermath of 1968.

And then there were those artists who just sought to inject some novelty into the sterility of their surroundings. The conditions were serious, but perhaps individuals didn’t need to be. Polish theater group Akademia Ruchu put on comical public performances where they would pretend to fall over invisible objects on the street.37 In other instances, they would queue in exceptionally long lines for seemingly no purpose at all. Avant-garde artist Endre Tót mailed zeroes to noteworthy recipients for “people who are nothing.”38

In a 1982 New York Times Review of Kundra’s The Joke, the general feeling of nothingness is plainly said:

A boyish prank? An innocent joke? Not on Ludvik's life. He is soon brought up on charges at his Party cell and slyly excoriated by a friend and comrade, Pavel. Party and university expel poor Ludvik, and he is shipped off, for ideological rectification, to work as a penal laborer in the mines. On his occasional leaves from the mines, Ludvik has a frustrated love affair with a frightened, almost speechless girl named Lucie.

It comes, like everything else in his life, to nothing.39

It was initially unclear whether any of this would ever amount to something. In the six-part series The Other Europe from 1987-1988, the interviewed dissidents show little indication they believed they would very soon be victorious and propelled into power.

According to Havel, the dissident has “no desire for office and does not gather votes. He offers nothing and promises nothing.”40 But once the unthinkable happened and the Iron Curtain fell, the public naturally turned to these dissidents for guidance. They were their moral heroes, and they wanted political promises. Votes were gathered and this literary underground, often to their own surprise, found their way into political power.

The End of a Literary Golden Age

The collapse of Communism caused an existential crisis among dissident writers. Despite the historic victory and promises of a better life, coming out from the underground brought confusion over the purpose of literature. Dissidents had to step down from their exalted positions with no special role. “Writers, who once represented mythical entities, now represent just themselves,” remarked Polish novelist Adam Zagajewksi, who humorously added that this suited him better.41 Yet others found themselves in a more unsettled state. Konrád pithily asked in 1991, “what is left when there is no more devil?”42

The confusion we see now among intellectuals here was absolutely predictable. It is very ironic, a cruel central European joke. Those who historically were always the opposition, who did not want power, are now the leaders.43

Central European writers once dreamed of living in a “normal society” where they had the freedom to create whatever they wished. But the truth was that their literary golden age was partially made possible by indirect state subsidization. Very few “recognized the simple truth that communist regimes had in many ways created for them a writers’ utopia.”44 Under repression, they had lived in their own enclosed “mad worlds” and now they had to exit.45 In the decade that followed the end of Communism, market liberalization eroded the literary underground both of purpose and financial backing. The years 1989 to 2000 saw the collapse of many publishing houses as well as pay for writers plummeting despite incomes on average rising.46

Yet, it wasn’t just a matter of bad pay and ennui. During Soviet rule, Central European dissident writers went to great lengths to develop their own language which was no longer relevant. They often relied on the passive voice to avoid accusations and naming names, but one could always read between the lines. The end of Communism meant writers no longer knew who “we” addressed.

As Hungarian writer Péter Esterházy remarked:

Once when a poet said “we” we knew who “we” was. Now that community of interest has been broken: the basic relationship between writer and writer, writer and reader, reader and reader, and their relationship to politicians – who occupied an entirely different territory – have all been broken up. Now we are fragmented. We always knew what we were against, but not exactly what we were for. Now when a politician – or a writer, for many writers have become politicians – says “we” we don’t know to whom he is referring.

Now I must take each and every word into my hands as if for the first time, and I must study these words to see what they contain now and what they might contain in the future. I need to make a whole new dictionary.’47

Hungarian poet Sandor Csoori, whose writing often spoke to peasant rural life, characterized the situation as a collapse of spirit. By the mid-1990s, it had “sunk to zero point” in Hungary.48 Politics was exploiting the difference between rural and urban life to procure votes, he argued, without any regard for the preservation of cultural heritage.

And what are we doing to protect our rural writers, our peasant artists? Nothing at all. And yet they have such a purity about them in their style, their vocabulary, in the verse forms and themes. They are craftsmen. When you read them it is like watching someone work a design in wood. They are the essence of Hungarian-ness. Our peasants, they are pure. They are our only hope.49

Although holding much self-doubt himself, Csoori could not help but feel that the intelligentsia had "lost touch with its ‘orphaned’ people.”50

The Promise of Politics

After the collapse of Communism, the dissident writer was left without a clear mission. Many stopped writing to enter politics, believing that political office could presumably take on the ideas that their literature once described. The most noteworthy example is Václav Havel, who would be elected the first President of the Czech Republic. As one Hungarian magazine editor told a journalist in 1990/1991, “There is no good writing at the moment. Everyone is involved with politics, I think. I don’t know what writers are doing, but they are not writing. That is all I can say.” 51

The dissidents were “politicians in spite of themselves.”52 The anxiety was perhaps best captured by György Konrád. In Antipolitics (1984), he confessed that “my worst nightmare is to have to tell millions of people what to do next.”53 As a skeptic prone to tragedy, Konrád viewed power as a ruiner of otherwise good people. “The most gifted people should be seers, not government officials,” he argued, “power is not a stage but a prison.”54 Konrád himself was a founding member of the Hungarian Liberal Party (SZDSZ), but retreated during the 1990s despite some believing he should be the country’s president.55

Some even suspected that dissidents only became writers because the door of power was never open to them in the last regime. This was the assessment of Hungarian critic László Kéry in 1990/91:

The east-central European writers have lost their constituency to the politicians.

It is clear from the way that the democratic opposition has been led by writers, and by the speed with which the writing fraternity has transformed itself into an active political stratum, that without the advent of "socialism” this class would not necessarily have become writers at all.

Indeed, it seems probable that a great number of them would rather have become professional politicians.

In many ways, according to the poet Csoori, “the transition came so suddenly that no writer has been able to catch up with its impact.”56 The shock of the 1990s overloaded the culture with consumerist excesses, appealing to the most basal desires and pornographic kitsch, not to mention criminality. In the realm of ideas, everything was aired out in the open. There was an explosion of “reportage, editorials, letters to the editor, special documents and studies, and cultural and political attacks and counterattacks” that were not present under Communism.57

It is as if the whole of Hungary has been reduced to the role of a tourist who is just passing through, quickly snapping up trifles and rubbish, not knowing good from bad. We see this perhaps worst of all in our journalists, many of whom were responsible for telling us how to be good communists, and who now tell us how to be good democrats.58

New battlefields opened up in virtually every direction. This was in no small part due to the oppositional character of the dissidents themselves. “I belonged to the opposition for many years – perhaps nearly 30 years,” Csoori said, “and now, even though my party is in power, I cannot rid myself of this habit.”59

At the moment journalists say that the ruling party has three sections: the populist, the nationalist, and the Christian conservative. What can I say that isn’t true? These three groupings — I feel I have all these things in me, but I still feel I am an oppositionist.60

Dissident writers were precise in their diagnoses, but lost their collective moral footing when the terrain irrevocably changed. Some gave in to opportunism, others to a desire for conflict, but the victory brought contradiction in all forms. Such contradictions were on full display many years later when leading opposition heroes like Václav Havel, Adam Michnik, Lea Wałęsa, and others voiced their support for the 2003 Iraq War.61 Their words were proudly touted by the Bush administration as clear evidence that the U.S. invasion was a righteous cause, endorsed by the world’s leading moral heroes.

Revisiting “Other Europe”

Central Europe has ceased to be “Other Europe” like it once was. The chaos of the 1990s gave way to a more stable 2000s, tamed by investment, NATO membership, and EU enlargement. Unsurprisingly, Central European dissidents are today often remembered in one-dimensional ways, their slogans and moral message reduced to political talking points. Maybe it could be said that their hasty turn to victory and power injured their names, now readily evoked by whoever finds it useful.

Still, the dissidents’ advocacy of civil society has been under-appreciated, especially as it relates to our own time. Sometimes extreme conditions shed light on the most fundamental questions, and the dissidents were probing them incessantly. They valued what Western societies take for granted, and documented how public life degrades when it is captured wholly by power. As they rightfully argued, when civil society is independently strong, power better reflects the shared social interest. Their observations take on new meaning in our distrusting present.

And just as importantly, dissidents explored the dark depths of ideology, and how it can easily capture minds and transform people into disposable means for an end. “An omnipresent ideological fiction can rationalize anything,” wrote Havel, “without ever having to brush against the truth.” It’s a salient observation in a time of the internet when so many feel uprooted. When faced with uncertainty, we are especially drawn to a story or ideology to ground ourselves to a fault.

These writers and artists passionately demonstrated that, when everything is stripped away and only one’s inner core is left, it is enough for life. The voices of “Other Europe” should be understood within the realities of their extreme time, but they still call out to the present with surprising relevance.

The reputation of the Soviet Union suffered greatly after 1968. Most famously, Maoists in China accused the Soviet Union of chauvinism and likened the invasion to Hitler’s annexation of Czechoslovakia.

Gale Stokes. The Walls Came Tumbling Down (1993).

Gale Stokes. The Walls Came Tumbling Down (1993).

György Konrád. Antipolitics (1984), pg. 1.

Antipolitics mainly blames the Yalta Conference of 1945 for abandoning Central Europe, claiming it would be the reason for a possible “Third World War.”

György Konrád. The City Builder (1987), pg. xv.

György Konrád. Antipolitics (1984), pg. 169.

Civil society is closely tied to the idea of “third places” (places of belonging that are neither work nor home), which have also declined. I wrote a piece on it here.

Klara Kemp-Welch. Antipolitics in Central European Art (2014), pg. 6.

Klara Kemp-Welch. Antipolitics in Central European Art (2014), pg. 6.

Soviet communism legitimized itself by taking the legacy of once-popular workers’ movements of the past and making it an instrument of their power. The reality was, by the 1960s/1970s it was actively suppressing non-sanctioned labor organizing in all forms.

This article is a good summation of post-totaliatarianism as Havel understood it.

Gale Stokes. The Walls Came Tumbling Down (1993).

The most-cited slogan of Havel’s The Power of the Powerless (1979)

Gale Stokes. The Walls Came Tumbling Down (1993).

Politics and Conscience (1984) by Václav Havel, translated here.

Barbara Falk. The Dilemmas of Dissidence in East-Central Europe (2003), pg. 324-325.

Michael Walzer. The Idea of Civil Society (1991).

David Ost. Solidarity and the Politics of Anti-politics (1990), pg. 4.

David Ost. Solidarity and the Politics of Anti-politics (1990), pg. 1.

Adam Michnik. Letters from Prison (1985), pg. 125.

Quoted in “Foreign Affairs: Needs of Civil Society,” The New York Times (August 29, 1989)

Politics and Conscience (1984) by Václav Havel, translated here.

David Ost. Solidarity and the Politics of Anti-politics (1990), pg. 19.

Klara Kemp-Welch. Antipolitics in Central European Art (2014), pg. 4.

Jirous was also the creative director of the legendary Czech dissident band The Plastic People of the Universe.

“The Other Europe” was the name of a six-part interview series on dissidents on the eve of the Soviet collapse. It’s also the name of a special collection of translated novels from Central Europe.

A good read on the author, Egon Brody, considered the mastermind of the Czech literary underground.

Like in Havel’s play The Memorandum (1967).

Klara Kemp-Welch. Antipolitics in Central European Art (2014), pg. 5.

Barbara Falk. The Dilemmas of Dissidence in East-Central Europe (2003), pg. 358.

Barbara Falk. The Dilemmas of Dissidence in East-Central Europe (2003), pg. 358.

Carl Tinghe. Hungarian writers in transition to democracy: Budapest diary, December 1990 (2010). Pg. 382.

Andrew Wachtel. Writers and Society in Eastern Europe, 1989-2000: The End of the Golden Age (2003), pg. 585.

Havel likened the life of a dissident to living in a “mad world.”

Andrew Wachtel. Writers and Society in Eastern Europe, 1989-2000: The End of the Golden Age (2003), pg. ??

Carl Tinghe. Hungarian writers in transition to democracy: Budapest diary, December 1990 (2010). Pg. 381.

Carl Tinghe. Hungarian writers in transition to democracy: Budapest diary, December 1990 (2010). Pg. 383.

Carl Tinghe. Hungarian writers in transition to democracy: Budapest diary, December 1990 (2010). Pg. 378.

Gale Stokes. The Walls Came Tumbling Down (1993).

Carl Tinghe. Hungarian writers in transition to democracy: Budapest diary, December 1990 (2010). Pg. 383.

Carl Tinghe. Hungarian writers in transition to democracy: Budapest diary, December 1990 (2010). Pg. 383.

Carl Tinghe. Hungarian writers in transition to democracy: Budapest diary, December 1990 (2010). Pg. 384.

As early as September 2002, Havel supported a preemptive military attack on Saddam Hussein and compared not acting to appeasing Hitler during WWII. Adam Michnik wrote in June, 2003 that the “collapsing World Trade Center towers made me realize that the world was facing a new totalitarian challenge.” Lech Wałęsa was the most lukewarm about the invasion, believing it should be a UN-led operation to reclaim its moral purposes, but still praised the U.S. for stopping Saddam.

Fantastic, sir as always.

Having lived through the times and being pretty close to the dissident millieu it's hard for me to comment. It has been complex. Maybe just about the idea that the writers were in fact politicians in hiding, people who would otherwise be politicians but were forced not to by the regime. I don't think it quite pans out.

Those who wanted to become politicians back then joined the communist party, they didn't write books. Also I would point out that couple of decades after the revolution barely anyone from the former dissent was still in politics. On the other hand, there's was no dearth of people with communist past.

Also, the political landscape after 1989 was very limited and some people may have been engaging in politics only because they've seen no reasonable alternative. There were no established parties (except of communist) and the general political landscape looke like this:

1. Former dissidents.

2. (Former) communists.

3. Petty crime rising to become organized crime and suddenly realizing they can co-opt the state.

The group 3. won in the end, but in 1990 they were still mostly invisible and the political struggle seemed to be between 1. and 2.