"What if your entire worldview was just because of near-zero interest rates?"

The old economic world may be leaving us, but its pathologies stubbornly remain.

Recently, I came across a piece in Bloomberg which explores how the entire worldview of newer traders on Wall St. was unraveling.

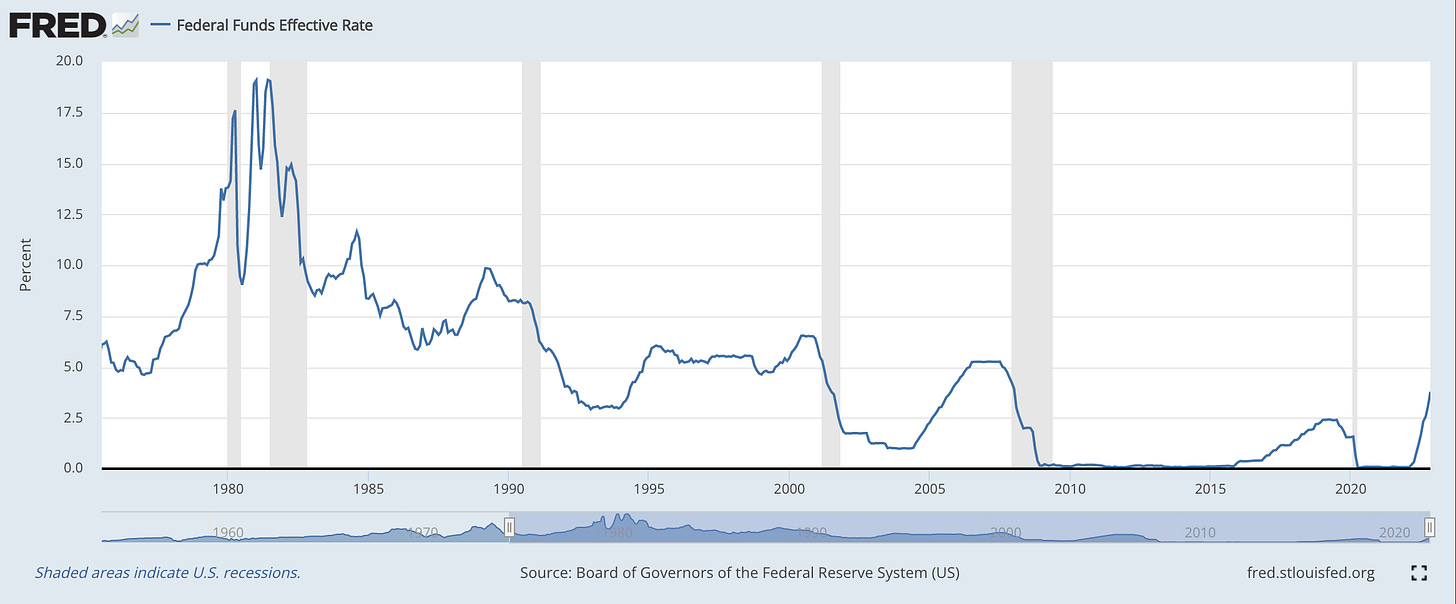

Since 2009, the Federal Reserve has kept interest rates at or near zero. Many other central banks did the same. For over a decade, banks could borrow money for little to nothing. It became the new normal, and the generation that entered Wall St. during this time is now disoriented, for they “do not know a world without cheap money.”

This story piqued my interest. Whenever people are humbled by the melting away of things they took for granted, now that’s a topic worth exploring.

But this is not just a story about finance or markets. The long period of ‘cheap money’ made for a strange time all around. The 2010s were a decade that “disrupted everything but resolved nothing,” as Andy Beckett wrote, and I tend to agree. The near-zero interest rate regime functioned much like an opiate. It was the water everything swam in, and it made the dysfunction somehow still functional.

The dysfunction bubbling in the background, however, kept accumulating in its many forms: diminishing state capacity, social fraying, hyper-polarization within political power, trust at all-time low, and actual productivity growth being negative or close to negative in many developed economies.1 Arguably, the lasting takeaway of the past decade-plus is how the public’s optimism about the future fell apart, especially as expectations about technology grew much more cynical.2 Sometimes, it seemed like the last vocal optimists left were investors and venture capitalists.

It ‘resolved nothing’ — but it also didn’t burst. While markets may have been roaring, some unfortunate long-term developments persisted in the background unabated. Now that we’re possibly turning a page, I can’t help but ask rhetorically: ‘what if it turned out that your entire worldview was only possible because of near-zero interest rates?’3

The point of this silly question is to consider just how much of an outsized role the Fed now holds. The circumstances produced worldviews that assumed this state of affairs had some permanence.4 It’s openly accepted now that much of finance capital has become a function of monetary policy. And since finance capital is now more important than ever to economic growth, it stands to reason that the Fed is also more important than ever. It’s Jerome Powell’s world: never before have I seen markets move so erratically in response to a once-boring Jackson Hole conference. Actually, the first time I ever even remotely paid attention to this event was this year, since some acquaintances of mine were trying to ‘trade’ it.

After the Great Recession, the Federal Reserve instituted a zero or near-zero interest rate regime. The philosophy behind it was simple. As outlined by Fed Chair Ben Bernanke in 2010, it’s known as the wealth effect.

Higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending. Increased spending will lead to higher incomes and profits that, in a virtuous circle, will further support economic expansion.

Higher stock and home prices effectively became a primary engine of growth. And henceforth, the Fed’s purpose became more and more intertwined with asset growth. It was a new kind of ‘trick down economics’ for the financialized post-Great Recession era. Other central banks followed the Fed’s lead, sometimes taking even more drastic measures. Four of them in Europe, along with Japan, unconventionally opted for negative interest rates.

All of this has led to weird idiosyncrasies, euphoria, and contradictions. Stocks ballooned, tripling in value since 2009. Aside from commodities, virtually all assets went up without discretion. Housing became the ultimate speculative asset. Financialization became a way of life. What even is value anymore?

Consider the following post-2009 developments:

Top corporations, especially tech companies, became flushed with an exorbitant amount of cash. This is a departure from the olden days of corporate behavior. They are so insulated that they might as well be institutions — “In recent years, the rise in cash held by U.S. companies has been dramatic, skyrocketing from $1.6 trillion in 2000 to about $5.8 trillion today.”

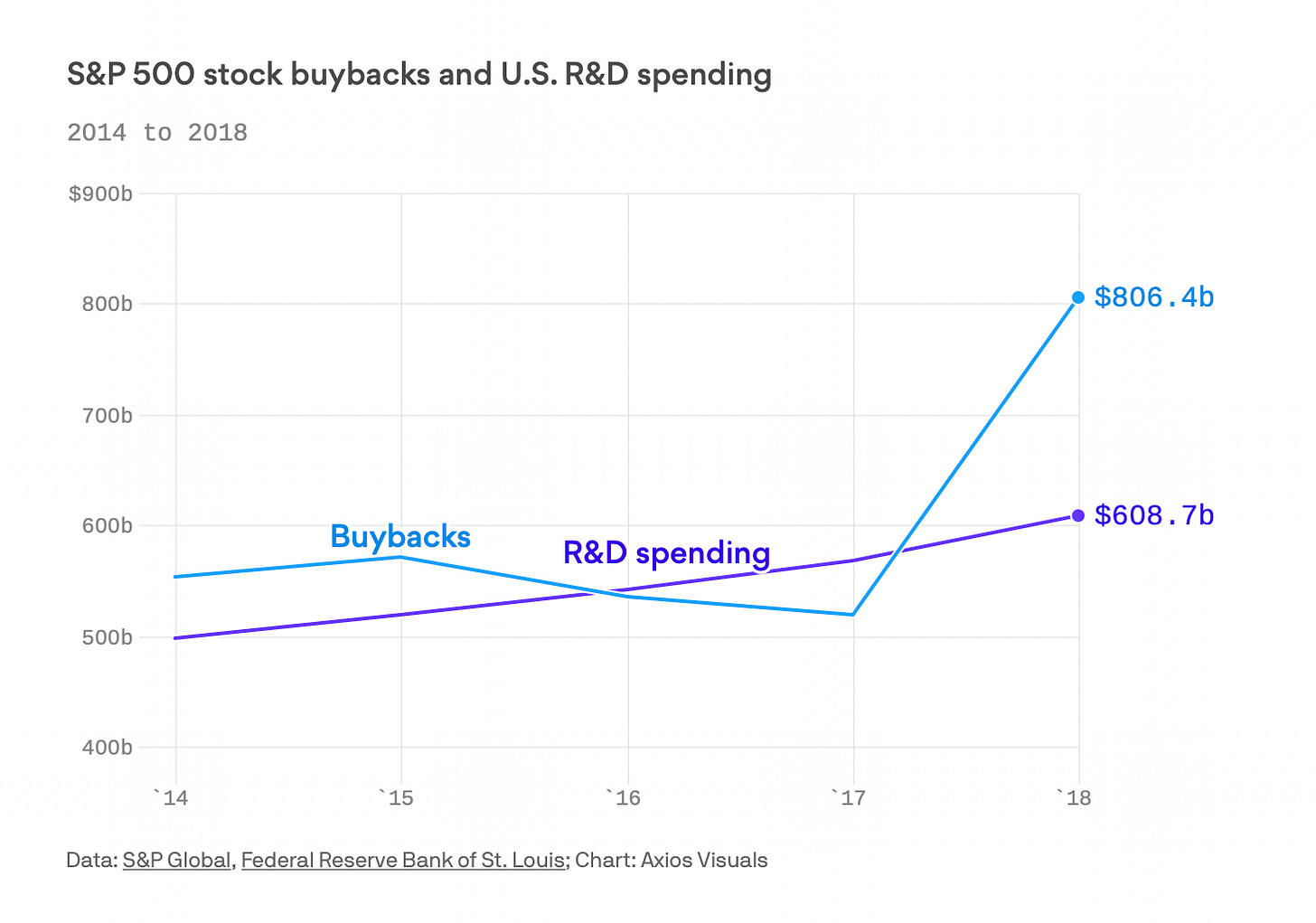

Related to (1), stock buybacks were a defining feature of the 2010s. By the end of it, they reached absurd levels. Between 2009 and 2018, S&P 500 companies spent around 52% of all their profits on buying back their own stocks, some $4.3 trillion. If we isolate just the 2010s, buybacks doubled compared to the previous decade. This development has been linked to structural economic changes, as discussed in this excellent piece by the Institute for New Economic Thinking:

In their book, Predatory Value Extraction, William Lazonick and Jang-Sup Shin call the increase in stock buybacks since the early 1980s “the legalized looting of the U.S. business corporation,” while in a forthcoming paper, Lazonick and Ken Jacobson identify Securities and Exchange Commission Rule 10b-18, adopted by the regulatory agency in 1982 with little public scrutiny, as a “license to loot.”

A growing body of research, much of it focusing on particular industries and companies, supports the argument that the financialization of the U.S. business corporation, reflected in massive distributions to shareholders, bears prime responsibility for extreme concentration of income among the richest U.S. households, the erosion of middle-class employment opportunities in the United States, and the loss of U.S. competitiveness in the global economy.

— Financialization of the U.S. Pharmaceutical Industry (2019)After a lull in 2020, buybacks have come roaring back in 2021 and 2022.

Part of the problem is that the buyback splurge often exceeded what was spent on actual, productive research and development, as shown below.

The top pharmaceutical companies represent some of the most egregious examples. Many companies also took the bold step to not even bother with any R&D at all! In 2018, for example, a majority of S&P 500 companies reported none whatsoever.

The 2010s were also the decade CEOs started linking most of their pay to stocks which inevitably changed their priorities.

One of the biggest winners of the post-2009 ‘cheap money’ period and its stock appreciation has been Vanguard. It’s now the number #1 holder of 330 stocks in the S&P 500 and on track to own 30% of the stock market in less than 20 years. Its founder Jack Bogle wrote an op-ed before he died expressing concern that funds like his now owned way “too much of the market.”

The investor share of U.S. housing is now at record levels, as is the cost of buying a home. Previously an ‘alternative investment,’ real estate has been officially inaugurated as the “equity market’s 11th sector” by the Global Industry Classification Standard.

Related to (6), the percentage of U.S. GDP represented in the relatively unproductive sector of FIRE (finance, insurance, and real estate) is at an all-time high of 21%.

And finally, as the Fed’s role has grown, so has politicians’ impatience with it when needing to win elections. In 2019, Trump lashed out at the Fed for not lowering rates to zero again or even under zero like it was in Germany.

However, the following year he got his wish, which was immortalized in this hilarious, must-see meme* from April 2020 (*for some reason, I can’t embed it anymore but watch it…)

It’s Pathological Now

After the Great Recession, financialization went cultural. John Luttig has argued this exact point in his 2021 piece Finance as Culture on his substack

. And like any culture, it has particular patterns of behavior and social sensibility, which have now seeped into the larger society.I would jokingly go as far as to say that the past decade, especially the past few years, has made a bit of a binary-choice gambler out of all of us. With the capacity for attention dwindling, the choice is either “it’s over” or “we’re so back.” Inflation falls 0.2% under expectations? We are so back. S&P 500 jumps 5% in a single day. This is the erratic, pathological leftover of the past few years and it’s unlikely to go away.

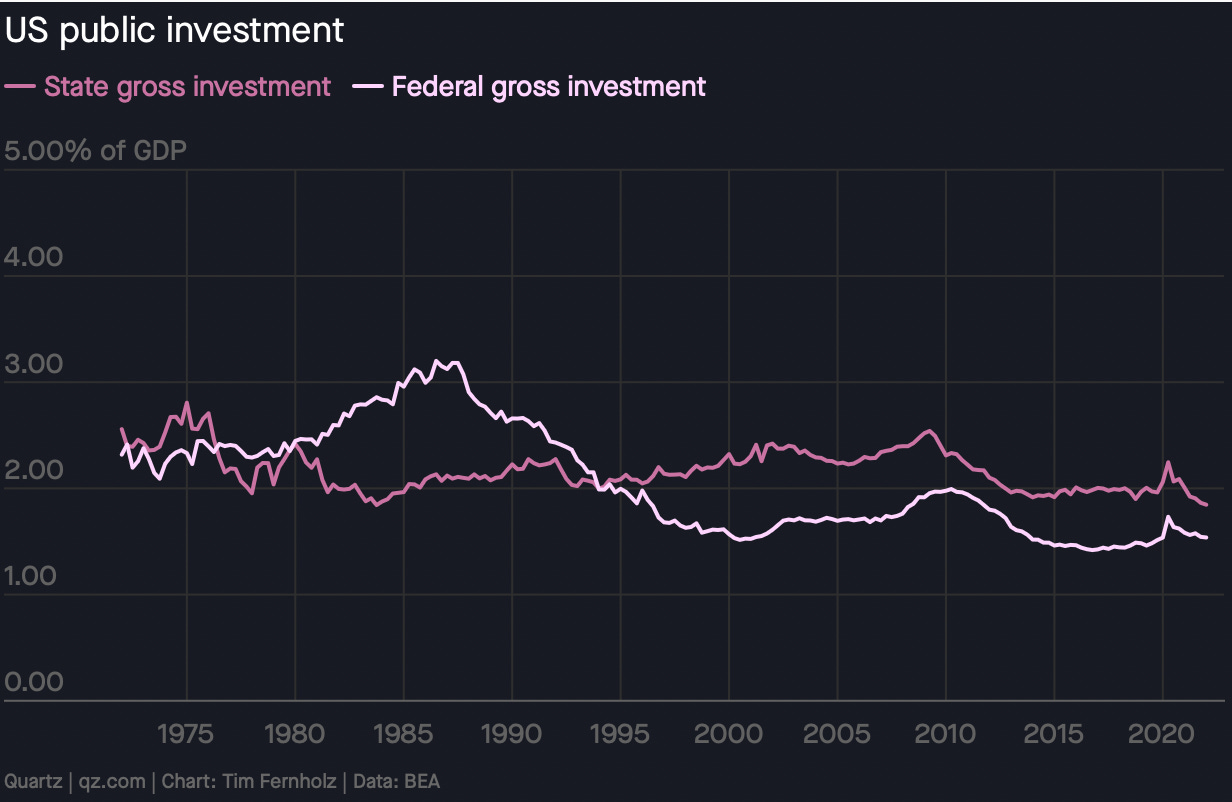

We can view 2020-2021 as the apotheosis of the decade-long frenzy that was the low-interest rate regime. In a fitting climax to it all, Congress did not even bother to trace where COVID relief funds went. Bloomberg writes that perhaps a quarter was lost to fraud. Fake identities were commonly used to procure funds illicitly. The pathologies of the state were on full display, believing that ‘more and more’ was a replacement for quality and competence. It's the ultimate analogy for the ill-conceived excess made possible by cheap money. The result was an unprecedented $5 trillion spent—more than double what the U.S. directly paid for the Iraq and Afghanistan War5—but which has led to little discernible benefit in infrastructure, public works, or any long-term quality of life metric relative to the dollars expended.

I write this all while not necessarily being for needless monetary restraint per se, either. But let it at least be measured dollar-for-dollar on its social benefit. One cannot help but feel frustrated over the squandered historic opportunity: public funding was anemic during this entire long period of ‘cheap money.’ If you’re going to do it, at least do it right…

The Fed may be hiking rates now, as is Europe for the first time in 11 years, but the pathologies that defined 2009-2021 are not leaving us. Those who grew accustomed to this world will not so easily accept the new one. In her book Permanent Distortion (2022), Nomi Prins argues that there is no real ‘out’ for this new arrangement.

The Gordian knot we find ourselves in now is that good economic news is bad financial news. A strong economy means that the Fed will keep hiking rates which is bad for financial assets. Such was the case with the recent strong jobs report, which caused markets to crash. If we had an actual recession now, stocks would paradoxically explode upward because the Fed would have to revert back to cheap money. This alone says everything about how the circuits of value within finance capital have grown disconnected from the economic base.

Now that we are supposedly turning a page, the hope is that the dysfunction accumulating in the background can be more thoroughly acknowledged. I already see some indication of this, with outlets covering the steep decline of sociability that’s gone unnoticed for too long. It’s a start. May attention be more appropriately applied now, since the investor is finally forced to temper expectations and be a bit more pessimistic like the rest of us.

From 2010 to 2019, U.S. labor productivity in manufacturing was negative for likely the first time in its history. In the UK, labor productivity for the decade rose a paltry 0.3% which was called the “statistic of the decade” — the worst since the early 1800s and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

With the blowup of social media and criticisms of the internet, optimism over technology and the future itself reached a new low. The NY Times called it the “decade of disillusionment.”

This formulation of this question was first posed to someone jokingly on Twitter in a reply, but now I can’t find the original. If and when I do, I will link it here.

12/11 EDIT: Found it! Special thanks to Martin in the comments.

In 2019, Bloomberg wrote that ‘waiting for rates to go up’ has become like waiting for Godot. Implying that it’ll never happen, it reads that the new normal has “changed everything.” Even as late as Nov 2021, CNBC interviewed a major investment firm that said the near-zero rates were “forever.” So much for that.

According to a 2020 report by the Watson Institute at Brown University, the direct cost of both wars was around $2 trillion. This excludes interest payments.

great article, and I agree with your observations.

Yet, the determining factor to me seems debt. With debt-to-GDP at current levels, I don't see a possibility for any major CB to implement a serious "survival constraint" i.e. interest rate over the medium term. I'd bet the FED lowers rates until early 24, otherwise the government is basically insolvent...

see some back-of-a-napkin calculations here:

https://www.pgpf.org/analysis/2022/12/higher-interest-rates-will-raise-interest-costs-on-the-national-debt

https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/national-debt/

Money is always cheap if the return on investment is greater than the interest rate. Things might be a bit different today in that the all-time low cheap interest rates universally inflated valuations across the board (so that there's no housing bubble to buy into following the dotcom bust like there was in 2001). This means sparser investment opportunities, but they are unlikely to disappear.

A quick check of the BLS ( https://www.bls.gov/oes/tables.htm ) shows that "Financial analysts" (code 13-2051) had employment of 228 thousand in 2007 (mean annual wage: $81,700), and 291 thousand in 2021 (mean annual wage: $103,020), which exceeds the population growth rate by quite a bit (not adjusted for age ranges), and misses inflation by about $1,900/year. Not too shabby.

For personal financial advisors (12-2052) this is 132 thousand in 2007 ($89,220) vs 263 thousand in 2021 ($119,960), beating inflation by almost $4,500/year.

In 2007 rates were not only at historical levels (4.6% average), but had been on a gentle up ramp for the previous two years.

"Since the 1980s, the federal funds rate has been trending downward to squeeze out more growth."

Is this actually *the* reason for the rate decreases (first to historic averages from the mid 90s to early 2000s, recovering to historic averages before the Great Recession)? Would not increasing government debt be a factor too (ala post-WWII rate drops)?

I definitely buy that it plays in to it, but financialization is primarily a consequence of legislative, judicial, and some law enforcement choices made over the last 50 years. A decreasing interest rate to historic norms (and then some following the Great Recession) is not a primary cause of financialization. It's just a minor contributing factor that itself has other, more important purposes.

"The thinking behind this strategy, as outlined by Fed Chair Ben Bernanke in 2010, is known as the “wealth effect.”"

Okay, this is news to me and really supports your point. We need to sideline "trickle down" economics. It is a known fact that consumer spending directly drives about 2/3rds of the economy. And it's a known fact that poorer people tend to spend more of their income. It's also known that any stimulatory effect of higher income people spending more because they feel wealthier is a double-edged sword when they immediately start spending less when their wealth drops. Therefore, if you want to consistently raise the GDP, in good times and bad, the best way to do it is to increase incomes of the poorer people in the economy. If instead what you want are boom and bust cycles then sure, inflate the wealth of the higher income earners.

"In his book Permanent Distortion (2022), Nomi Prins argues that there is no real ‘out’ for this new arrangement."

Enforcing existing laws, clawing back various regulatory slack (such as allowing stock buybacks, which used to be regulated as market manipulation), and getting rising-tide economists in the Fed would help.