Weekly Retrospective #4

Tea with the Mujahideen; What Is "Hyperpolitics?"; One Year of War in Ukraine; and a Murder at the Institute for Social Rejection

This is the fourth installment of my review series, where I unpack a few essays and topics I’ve been thinking about in the past week. It’s a cross-section of what this newsletter is all about.

But first, I have a minor update: I am trying out the AI-generated world of audio.

Let me know if it’s any good in the comments. It is admittedly a bit tedious to set up, but I’d be willing to do it if people enjoy it. Just keep in mind, there are a few photos in this piece so you’ll miss them if you just listen without reading along.

The first story for this weekly picks up on something I covered in a past review.

Tea with the Mujahideen

About two weeks ago, I covered a story about the malaise afflicting Taliban members now having to adjust to civilian life. In their letters they described mindlessly browsing Twitter in the office, feeling inexplicably “bored with it all” as they worked their 9-to-5 jobs. While being humorous, it was also oddly endearing in how earnest it was.

Journalist David Oks has also been in Kabul, Afghanistan recently. In a piece for Palladium Magazine, he explores how the “West Lives on in the Taliban’s Afghanistan.” It starts with some tea in a cafe.

I was in a Turkish-style café on the top floor of Afghanistan’s only shopping mall with a few young Afghans, waiting for green tea and rice pudding.

My Afghan friends were chatting loudly, in a fluid blend of Pashto and English. I, only half-understanding them, was puffing away at a cigarette while I watched Terminator: Dark Fate subtitled in Persian on the television above us. A few tables away, some Talibs were talking quietly and occasionally glancing over at the other patrons smoking hookah and thumbing their phones.

The crowd Oks was accompanying in Kabul was a young group of Afghanistan’s new online crowd.

The Afghans with me represented a cross-section of the country’s plugged-in youth. They described things as “based” and joked that people were “triggered.” When they were teasing each other, they used the term “soyboy,” which was by now a couple of years out of date in America. One was a YouTuber with a large audience in the Middle East, who produces Arabic-language content about Afghanistan; another was an ambitious entrepreneur, born in a refugee camp over the Pakistani border, and now a successful saffron exporter with side ventures in journalism and cryptocurrency; another, my first contact in the country, was an influencer whom I’d grown to trust over games of Counter-Strike: Global Offensive.

Oks goes on to discuss how the Taliban rules this isolated Islamic Emirate, which no other nation has officially recognized. The country has no constitution, with the final say on all major governmental matters being with the cleric Hibatullah Akhundzada.

In its governance, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan has no desire to imitate the West, openly disdaining how other Islam-majority countries try to do so. As Oks writes, “On walls throughout Afghan cities, the regime has emblazoned a slogan representing its remarkable confidence: ‘First Islam, then Afghanistan.’”

But yet, even in this hermit society of revolutionary religiosity, a modicum of globalization exists.

The longer I stayed in Afghanistan, the more the contradiction between the Islamic Emirate’s otherworldly aspirations and the compromises demanded for stability and development became evident.

Even the triumph of the emir’s program represents only a fleeting victory. It harkens back to a rural Pashtun culture that is fading, even in a place as anachronistic as Afghanistan. It has little to say to younger Afghans, or even to younger Taliban—often more exposed to global culture and prolific in their use of social media platforms like Twitter or Instagram.

They regarded the outside world not with hatred, but with a rich and earnest curiosity; they bore no ill will toward the West. As a guest in their country, they treated me with deep warmth.

This nexus existed in the urban center and was still a minority. A majority, around four-fifths of the population, still lived in the countryside. Nonetheless, there was an understanding that the peace after decades of war was a “godsend.” Many youths were eager to enjoy their lives of newfound normalcy.

These were not Western liberals: they had friends among the Taliban, and were quick to defend regime decisions I found abhorrent, like the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas. But these subjects of the Islamic Emirate could not be kept from watching Stranger Things or Game of Thrones or Japanese anime; they had a better knowledge of Breaking Bad than I did. On Twitter—they, like so many Afghans, were avid users—shared soyjack memes and called themselves “sigma males.” They talked about feminism, “LGBTQ,” and pronouns—strange things to complain about in a country where women can’t go to school. They were becoming Westerners: culture war, America’s most successful soft-power export, was their induction. The younger members of the Taliban, online enough to follow Andrew Tate, were not immune.

And while these young men were still a tiny minority, they were also the bleeding edge. Social modernity is not kept out by the barrel of a gun: the internet is the ultimate vector of Westernization.

Oks comes to the conclusion that the Taliban’s rule is surprisingly fragile, but not for the reasons one would suspect.

The Taliban won the war; but in the long run, the social modernity they so bitterly resisted is on its way. Even as my Afghan friends professed their conservatism and religiosity, they were yet to get married or have children—at ages long past when their parents were doing so. The direction of things to come seemed obvious.

Oks ends his piece by describing a conversation over tea he had with disaffected members of the mujahideen: individuals who were recruited as suicide bombers, but were not given the opportunity to be martyrs because of the war’s end.

What was it like, I asked, to make the transition from mujahid to bureaucrat? The one who spoke the best English—he had given himself the moniker “Mr. Young”—responded quickly.

“The feeling of the ambush, the moment of waiting for the American convoy, the excitement of the battle. We miss it.” “Martyrdom,” he said, “would make me much happier than being a bureaucrat and working in the ministry. On the word of Sirajuddin Haqqani, we would happily blow ourselves up tomorrow!”

Hearing his words, it was hard not to feel the sense that something had passed away. It was like listening to a cowboy reminiscence about the closing of the frontier.

I did some snooping around after reading this piece because I found some of it hard to believe. But I did, in fact, locate a few of the individuals that Oks was likely with. One does run an online Saffron business and is very pro-Bitcoin. Another co-hosts a podcast called Afghan Eye. There are many others. Clearly, there’s a digitally-native but oddly pro-regime group of urbanites there who are growing in number on Twitter and elsewhere.

Reading this, one gets the clear impression that this globalized world is heavily steeped in Americanism — from the concerns to the in-jokes, it’s Americanism all the way down. As the Economist covered in 2021, social media is exporting American political culture worldwide en masse.

Oks’s piece is a reminder of how remarkably deep this influence really is.

What Is “Hyperpolitics?”

Something strange is happening to politics these days.

On the one hand, we live in highly-politicized times. More people than ever are painfully aware of the world’s fragility. Many have become increasingly catastrophic in their worldview. From corporations to cultural institutions, organizations are today eager to broadcast their allegiance to some cause. Formerly meek and establishmentarian figures have become radicalized and see the specter of fascism everywhere. Today, society is being emotionally mobilized almost constantly, politics is visible everywhere, and “the personal is political.”

Yet, at the same time, there have been so few lasting mass movements or parties, which was commonly associated with such energies in the past. People are seldom mobilized collectively to great effect. Populist forces on both the Left and the Right have fizzled out with spectacular speed. The defining outcome of the present moment has been deepening cynicism, as trust in institutions plummets to all-time-low and all authority becomes increasingly suspect.

The present has us caught within the extreme emotions of politicization without the actual communities and activities of politics. In his latest piece, Anton Jäger calls this new period of ours as hyperpolitical.

“Everything Is Hyperpolitical” makes many of the points I just stated: about how “politics” has dissociated itself from the social bases that once imbued it with meaning.

As Jäger writes:

The rapid individualization and decline of collective institutions… has not been halted. Barring some minor and mainly digital outliers, political parties have not regained their members. Associations have not seen attendance rise. Churches have not refilled their pews. Unions have not organizationally resurrected themselves en masse. Political competition is still highly constrained, driven by a narrow cartel of career politicians and specialists ever at the mercy of hostile markets.

Many of these same trends I relatedly documented in my piece on the social recession. It’s a question that has occupied me for a while now. The social bases that once used to translate to “political communities”—class, religion, civic organizations, third places, and so on—all of them have eroded. In turn, the public has become alienated from what was politics. This trend is especially visible in the United States, but is noticeable in most other democracies.

Amid this erosion, the political classes of today are increasingly looking for a public to represent rather than the other way around. They have become like an ant mill, marching in a circle aimlessly, as the public underneath them has grown far more separate, distrusting, and sometimes even hostile.

Once conferred with social meaning, politics was previously understood as a kind of “home within a home.” For example, Jäger recounts how this was the case for the Italian filmmaker and poet Pier Paolo Pasolini in the mid-20th century. Pasolini was an avowed communist and here is how he described the Italian Communist Party (PCI):

a clean country in a dirty country, an honest country in a dishonest country, an intelligent country in an idiotic country, an educated country in an ignorant country, a humanist country in a consumerist country.

Regardless of what you think of that politically, consider the meaning behind the statement. The same can be said for the right-wing and its religious networks.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, the right built an equally impressive strip of fortifications across capitalist society around churches and neighborhood clubs. “Everything was Catholic in the experience of a Catholic,” a Dutch journalist recounts of her upbringing, “and one was a Christian 24 hours a day.”

Jäger places hyperpolitics as a period starting from the 2008 Great Recession onward. Hyper-politicization therefore springs from a general decline of social bonds and belief in a collective future. But still, throughout the essay, Jäger seems to avoid defining his term outright. Much of the essay is preconditioned on a sort of reading of “vibes,” although his examples are compelling.

Something has surely changed, but the hyper-politicization Jäger is describing is not merely a restlessness without use. Amid a collapse of social trust in the state, hyper-politicization and constant emergencies confer badly needed legitimacy to power. I think this is key, and it’s a topic I want to explore in the future.

For now, I wanted to share this fascinating piece while I collect my own thoughts for a longer standalone response.

Read the rest of Jäger’s essay here.

One Year of War in Ukraine & What Comes Next

About a year ago on February 24 2022, Russian troops formally set foot in Ukraine and began the war that today shows little chance of de-escalation anytime soon. It is undoubtedly the one event that has unsettled me the most, especially since I still fear what may come of it.

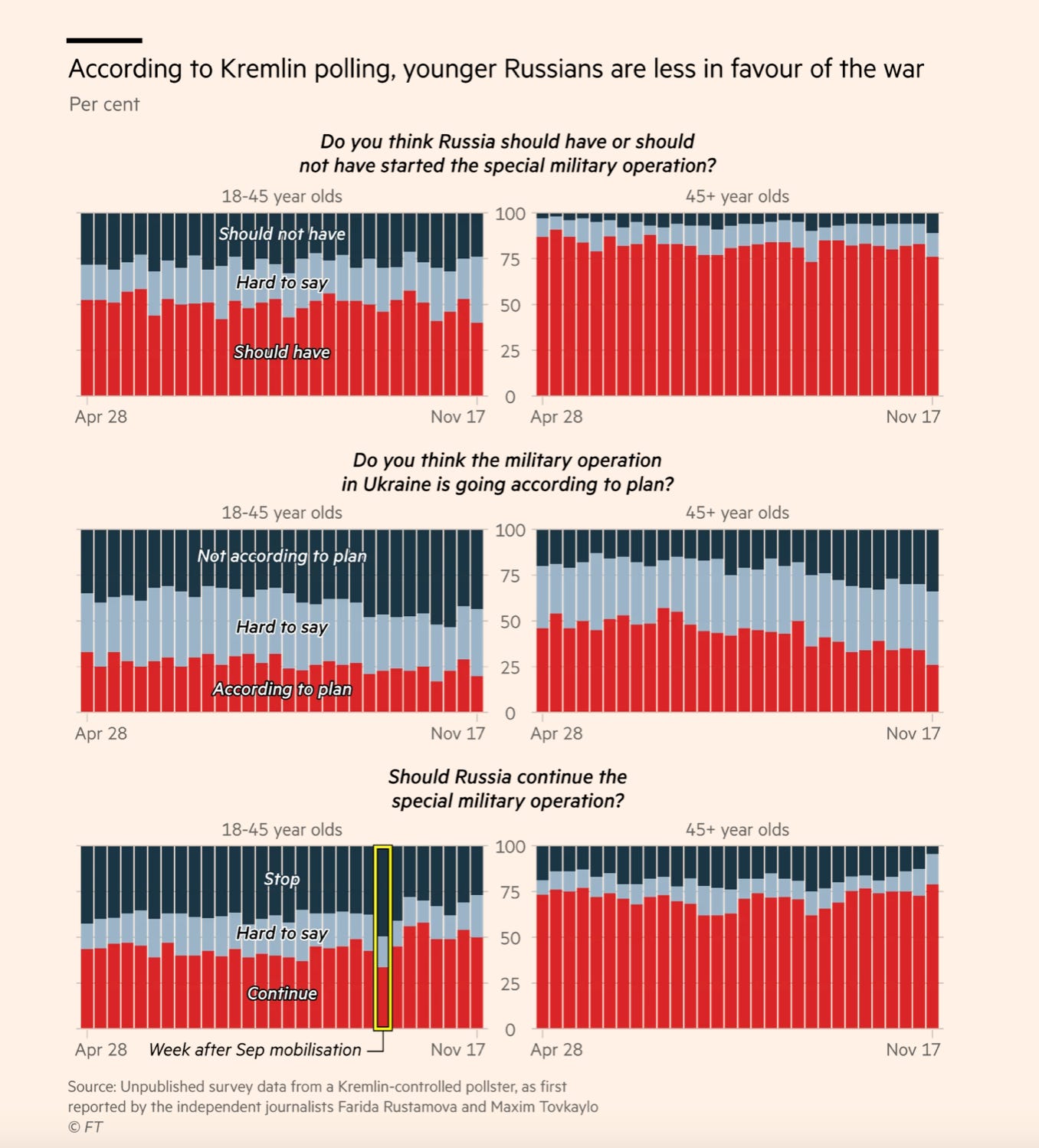

The past week has produced so many essays and analyses looking backward at how the war started and what the future may hold. Rather than review these pieces, most of which do not say anything new honestly, I thought it would be more useful to share some data crucial to understanding where the war is likely headed.

Ultimately, the future of this war hinges on Russia and its capabilities. This past week, The Financial Times presented some data on how Putin’s state is faring one year into the war.

Although we cannot be sure what the exact numbers are, they nonetheless make clear that this war will last much, much longer. Russia is further increasing its defense spending to at least a third of its GDP in anticipation of an offensive in the spring when the icy ground thaws.

Perhaps what is most interesting about the past year is how much the world has been transformed.

The takeaway lesson is that Western economies no longer dominate the world like they once did. Trade with China, India, Turkey and other nations has almost completely filled the hole left by Western sanctions.

Russia has made its core strategy opportunistically courting the Global South by tapping into anti-Western attitudes over past colonialism. The lines of this ‘new international order’ are shown below.

As Russia looks to Asia, the most in-demand language in the country has become mandarin Chinese. Russian imports to India have also soared over 400% since the war started.

This pivot, coupled with increased revenue from oil and gas, has allowed Russia to defy expectations of a depression. The IMF now projects it will just barely etch out positive growth for 2023.

But economics is just one part of the story.

The war has famously led to many Russians leaving the country, probably never to return. The extent of the brain drain is not yet clear, but we do know that over 500,000 people have left so far.

Still, a vast majority “support” the war. Not that they have much of a choice anyway—but public sentiment is nowhere near a boiling point where it would put Putin’s power at risk. There will be no “regime change” unless something catastrophic happens.

Read the full Financial Times report here.

These stats are sobering for a number of reasons. Overall, my interpretation is that Russia possesses the means to force a pyrrhic victory. It would come at an extremely high cost though. Suing for peace is the best outcome for both sides here, especially Ukraine. More and more people are coming around to this view as of late.

But is this a likely outcome as of now? Sadly not at all, which is why this is so worrisome. Generally, wars last a long time when “both sides have conflicting estimates of their bargaining power.”1 This is called the problem of 'mutual optimism' in regards to war.

This same scenario played out on the Western Front of World War I, even though none of the powers benefited. The battle line moved a mile forward, a mile back, with little progress whatsoever despite killing countless people and lasting four years.

This same grinding war of attrition resembles what is unraveling now in Bakhmut’s trenches which some have compared to the Battle of Verdun (1916). The issue is, Russia being larger, it can afford to throw away many, many more lives into the front lines than Ukraine can. We are stuck in a quagmire situation where there are frankly no longer any stabilizing outcomes.

A Murder at the Institute for Social Rejection

Lastly, I would like to share a satirical review of a book that does not exist. It was written by someone I believe I know, but who has decided to remain anonymous, publishing under the name “Coppelia Gray.”

By some stroke of mad wit, Gray has put together one of the strangest texts I have had the humorous pleasure of reading in a long time. It is the story of a man who sought to change psychoanalysis forever, but was tragically murdered!

At dawn on a November day in 1928, staff at the Institute for Social Rejection in Split, Croatia made a horrifying discovery — the cold, lifeless body of their unfortunate director, Ottoman “Otto” Fingerhof, dead in his study for some six or seven hours.

His great-grandson, Fyodor Fingerhof, tells his story in a book titled, Unconscious: An Olfactory History of the Fingerhof Family.

A little about Fyodor, the author:

The celebrated author, Fyodor Fingerhof, is a professor in the Post-Humanities Department at New York University, and well known in academic circles for his theory of “suspensivism” — the idea that at its most irreducible core, the genre of every true work of art is suspense. Using a French neologism, suspensivité, he defines the crucial characteristic of all great art as “A suspension at the threshold of representation, of truth and lie, real and unreal, trivial and transcendent, metaphysics and irony.” His aesthetic theory is laid out most succinctly in the now-classic essay, “The Dangling What,” published in The Critical Enquirer (Vol. IX, Oct. 2010), and more extensively in two semi-autobiographical monographs, The Sedentary Narcissist (2009), and its sequel, The Tenured Anarchist (2014).

Fyodor was inspired to write about his great-grandfather, Otto Fingerhof, because he felt his idea was lost to history, even shunned by Freud himself.

Otto Fingerhof’s idea was that the real inner machinations of the mind all came down to smell. “The nose,” as he proclaimed in a lost lecture, “is the royal boat to the unconscious.” On account of modernity, Fingerhof came to believe that the 20th century had become a “scentless century” — much to our psychological detriment.

Because of the so-called progress brought by Modernity, and the dominion of “Faustian” Western civilization, the olfactory capacities of man have atrophied into barely functioning artifacts of an ancient lifeworld.

His best-selling monograph, Twilight of the Nostrils (1926), is now known only among a handful of historians of German holistic pseudoscience of the early twentieth century, or accorded a rare footnote in a philosophically inclined work on the history of perfumery.

Modernity, as Fingerhof argues, unleashed industrial-scale research on olfaction, which sought to characterize, quantify, colonize, and monetize our most-resistant sense. Paradoxically, the new era also caused an olfactory decline by eliminating the panoply of odors, vile or pleasant, that had once beset or beguiled the nasal cavity in daily life — perhaps even our capacity to smell in itself, which cumulatively builds on experience and is a fundamental component of our being in the world.

The new era’s remorseless violation of space and time obliterated the ancient agrarian mode of life, in which humans were still part of the natural “noseworld” (nasewelt).

A heightened or superior sense of smell, as occurs temporarily in some diseases and pregnancy, or permanently (e.g., in professional “noses”), suggested a more primordial state — the attainment of a closer, animal engagement with the fundamentally erotic essence of Being.

“Eros,” Otto Fingerhof proclaims in his journal, “leads me by the nose” (Feb. 18, 1922).

Suppressed by the “cabal of mainstream Freudians,” Fingerhof went on to form the Institute of Social Rejection in Split, Croatia.

[The] first iteration of the institute was specifically devoted to psychoanalytic research, even boasting in-patient facilities for immersive treatment of the most serious and confounding cases. Regular patients, mainly neurotics and hysterics with olfactory symptoms, were treated in hour-long sessions at the Institute’s smaller adjoining facility, the Mare Nostrum Clinic, where they received a customized therapeutic approach to their psychonasal woes and metaphysical malaise.

Whereas Freud’s office boasted a world-class collection of priceless antiquities, in Fingerhof’s white-oak–paneled study, staid Viennese tradition clashed with voodooistic ornament. As several notable patients observed in their published diaries, the space resembled a shaman’s den, the lair of a practitioner of the occult arts.

On any random afternoon, antipodean incense, a sodden kitten or ash pan, a flaccid borscht or crusty finger, an unaccountably stained cravat, or even worse scents might assault the patient’s sensorium. Smells, however, were catalogued with positivist precision. An entire wall had been fitted with a magnificently wrought apothecary cabinet, adorned with carved faces and gryphons in the Breton style. Its complex system of small drawers and cubby holes creakily housed some 10,000 samples of scents in airtight vials and jars. Odors were ordered according to the Institute’s proprietary taxonomy and system of identification.

But soon, too, came the “stench of death.”

Fingerhof, whose eccentric methods were gaining notoriety, was tragically murdered in his study in November 1928. The case was closed without any explanation in 1929.

As a friend who wrote to me said, may Fingerhof’s tragic death “weigh like a nightmare on the nostrils of the living.”

Read the rest here, it’s worth it.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/25766259

Thanks for that. I'm going to go around the rest of the day muttering "nasewelt."

I listened to the Ai-generated podcast version. It was good. Fine.