The New Vertigo Years

Over a century ago, the world felt anxious and unsettled much like today

If you had to pick a period that most closely resembles how we experience life today, the start of the 20th century might not be the obvious answer. Life over a century ago seems like an altogether different world. Yet, it was the beginning of what we’d today recognize as modernity. A deep anxiety pervaded the social climate, especially in Western Europe, as every aspect of life was being upended.

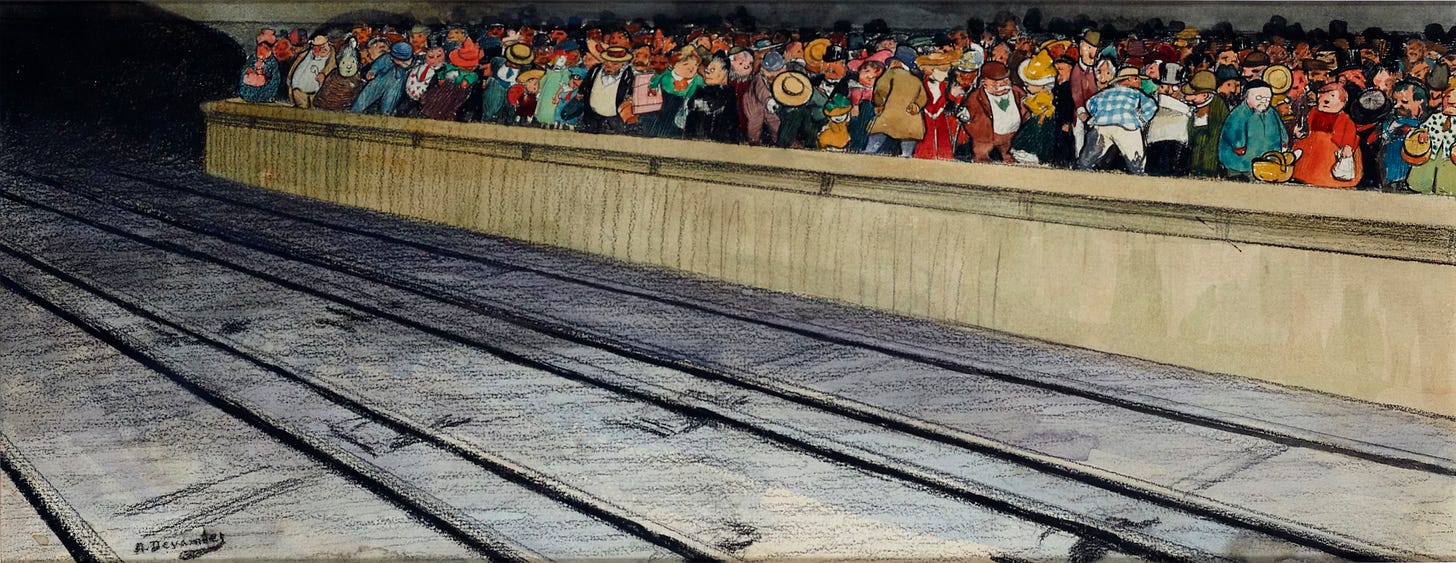

This was a time of decadent wealth and competing empires. Technology and science were advancing at a rapid pace. Cities ballooned in population as more people joined the working and middle classes. Industrialization brought modern-day conveniences, and mass media emerged to satisfy the eager public. Labor unrest and mass politics became a fact of life. Many experimental art movements took shape, as the old ways to describe the world needed updating. It was accepted that accelerating change and exponential growth would be the new normal.1

Some rejected where this new world was headed, while others accepted it. But regardless of where one stood, the overarching feeling for the average Western European—and the one aspect we relate to the most today—was speed. Things were moving too fast, everything was up for grabs, and there was no telling what kind of society would emerge or who would ultimately wield power.

The years between 1900-1914 have appropriately been called by historian Philipp Blom as the “vertigo years.”2 To find your footing in this dizzying period so often meant jumping into the unknown or, as many did, sleepwalking through it and hoping things would sort themselves out.3 Technological innovation remade cities into bustling metropolises, and the rapid transformation caused many to question what they once took for granted. As possibilities opened up, some artists and writers even found the newfound freedom exhilarating. While few truly expected the breakout of World War I in 1914, the uneasy atmosphere made the unthinkable possible. As writer Robert Musil wrote after the war, “we were simply lacking the concepts with which to absorb that which we experienced.”4 The vertigo years passed like a visceral dream.

You can’t help but read Blom’s The Vertigo Years (2008) with today in mind. Like then, our present is defined by its relentless pace. The states and people involved are clearly different, but that vertigo feeling has now expanded to include all of us, since for the first time roughly half of the world is part of the middle class and the vast majority is plugged in online.5 We are all arguably going through our own vertigo years, with similar anxious uncertainties about the future.

To read about the early 20th century is to look into a society that was struggling to keep up. Emotions ran high, tension was everywhere, and there was this nagging sense that the old rules no longer applied. “This new world was a merciless place,” Blom writes, “dividing humankind into those who coped and those who did not.”6

Losing Your Sense of Self

During the 1890s, the famous Austrian physicist Ernst Mach split from his scientific colleagues. To try to understand individual psychology in hard scientific terms was foolish, he argued, because the self is not a coherent unit.7 Each person’s experience was just a temporary collection of sensations whose causes are beyond our comprehension. The self had no directional center or permanence. “The ego cannot be saved,” Mach wrote, because the ego is nothing more than “convenient fiction.”8

For many young artists and writers in Vienna, it was as if Mach was speaking directly to their feelings of displacement. Mach’s ideas would be brought to a wider audience by Austrian essayist Hermann Bahr in 1903. He also coined the term “modernism” to describe the new genre of literature it inspired. The psychological profile Bahr laid out captured the mood: the ego was temporary, we are now unable to feel continuously, and our internal lives are utterly disjointed.

Man no longer moves towards objects through an act of will, he no longer chooses or examines objects: the world has dissolved, the objects move incoherently past the incoherent man. He forgets everything, as he has no continuity.

All that he ever has is that which the moment throws into him. He lives from this, exists through it: nothing else is in him except that which has come to him from the moment.9

It was an idea that struck at the heart of Bahr’s home country, Austria-Hungary, with its age-old obsessions with ego, noble titles, strict decorum, and traditions. It also suited the fast-paced, moment-to-moment experience of living in a chaotic city. A circle of writers called Young Vienna took up Mach’s ideas passionately.

Hugo von Hofmannstahl, one of the most distinguished writers of the circle, was a common attendee of Mach’s lectures. Hofmannsthal was growing frustrated by what he felt was a wall between his experiences and how he could express them. He explored these ideas in a fictionalized letter to philosopher Francis Bacon called The Chandos Letter (1902).

In it, Lord Chandos writes to Bacon about a world he no longer recognizes.

For me, everything disintegrated into parts, those parts again into parts; no longer would anything let itself be encompassed by one idea.

Single words floated round me; they congealed into eyes which stared at me and into which I was forced to stare back – whirlpools which gave me vertigo and, reeling incessantly, led into the void.10

While daily life gave him vertigo, Lord Chandos also writes that over-stimulation overwhelmed him to extremes and produced manic episodes. In those moments, he thought he was onto something, but the feeling never lingered and produced little coherent thought. “I could present in sensible words as little as I could say anything precise about the inner movements of my intestines or congestion of my blood,” he writes.11 The constant stimulation did not clarify his thoughts, it just paralyzed him further. “I have lost completely the ability to think or speak of anything coherently.”12

Exhaustion and Starting Over

The vertigo years saw breakthroughs in psychology, and one of the most common diagnoses was neurasthenia or “nervous exhaustion.”13 It was thought that the body could not keep up with the demands of modern, industrial life. The illness was also known as “Americanitis” since it seemed to especially affect professional Americans with fast lifestyles.14 Other diagnoses, like anxiety, neurosis, and hysteria also filled the medical literature of the period.15 Lacking solutions, “rest cures” were commonly prescribed to sufferers. Neurasthenia as a diagnosis has since been abandoned but is very similar to burnout syndrome, which became a regular diagnosis after the 1970s.

Both neurasthenia and burnout are diseases of exhaustion, common to both the early 20th century and our current time. And the fractured self that Bahr, Hofmannstahl, and others described also relates to our current sensibility. We, too, live in a kind of extended present as scattered and fleeting selves. Feelings linger momentarily, our routine of life is constantly disrupted, and being rooted is increasingly difficult.

Yet, many artists and writers of the early 20th century leaned into this modern reality. If the self was fractured, maybe it was time to proudly separate oneself from the past. Tradition was thought to provide no answers. Many deliberately broke from the 19th century liberal culture their parents were raised in and sought entirely new definitions. Innovators emerged in all spheres of life: music, art, politics, philosophy, economics, architecture, psychology, and more.16 But all of these original ideas were linked to the more fundamental fact that one’s sense of self was fragmented, and everything therefore needed to begin anew.

The uneasiness, however, remained and there was this unconscious longing to be saved from the incessant pace of life. The tragedy was that many projected these feelings onto World War I when it broke out. For Hofmannsthal, he undoubtedly saw it as a blessing.17 Full of jubilation, he thought, finally there was moment for us all to be reborn. Maybe now, the whole of society could finally be united under a common experience and cause. Others writers like Robert Musil and Stefan Zweig also fell under this spell, but came to regret their naive enthusiasm as World War I dragged on.

Information Overload

One of the dominant trends of our own time has been the parabolic rise of information. According to latest estimates, some 402 million terabytes of data are created online daily, and this number has continued to increase yearly for the past few decades.18 Since the 1970s, we have been living in the “Information Age” which has come with its own psychological problems: cognitive overload, decline of attention, desensitization, addiction, burnout, and a struggle to find meaning amid the avalanche.19

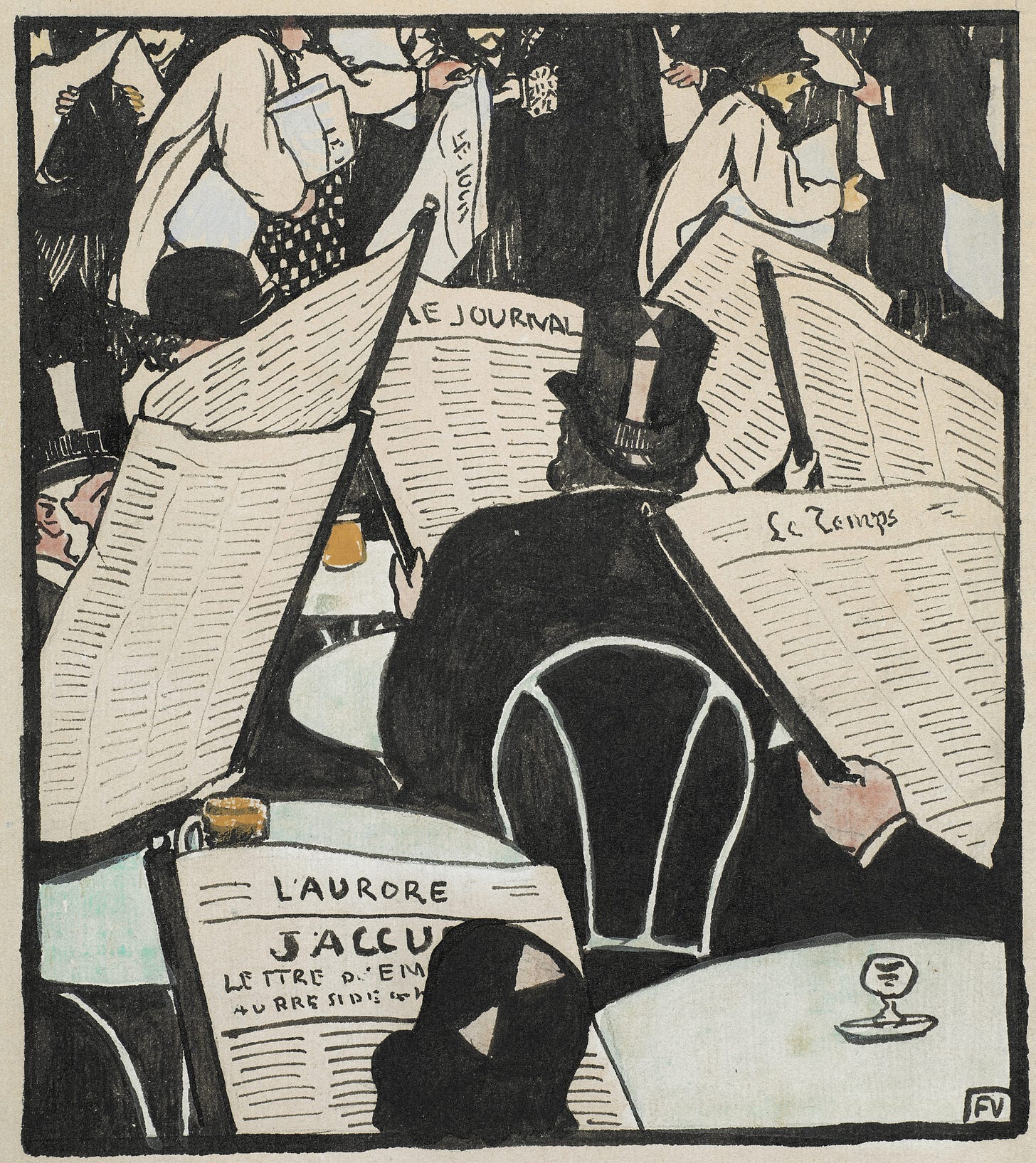

The vertigo years of the early 20th century was caused by its own avalanche of information, led by the explosion of print media. High-speed rotary presses and new typesetting machines made print media ultra-accessible and cheap. Increasing literacy also meant there was now a mass audience to read them. The demand was so high that some newspapers even had multiple daily installments. In just Germany alone, thousands of newspapers printed some 14 million copies per day by 1912.20 In England, The Daily Mail was the first publication to sell a million copies daily as early as 1896.21 It was also the first British paper to have a majority-women readership and catered mainly to the lower-middle classes. And in France, daily press circulation reached around 5 million per day by 1910.22

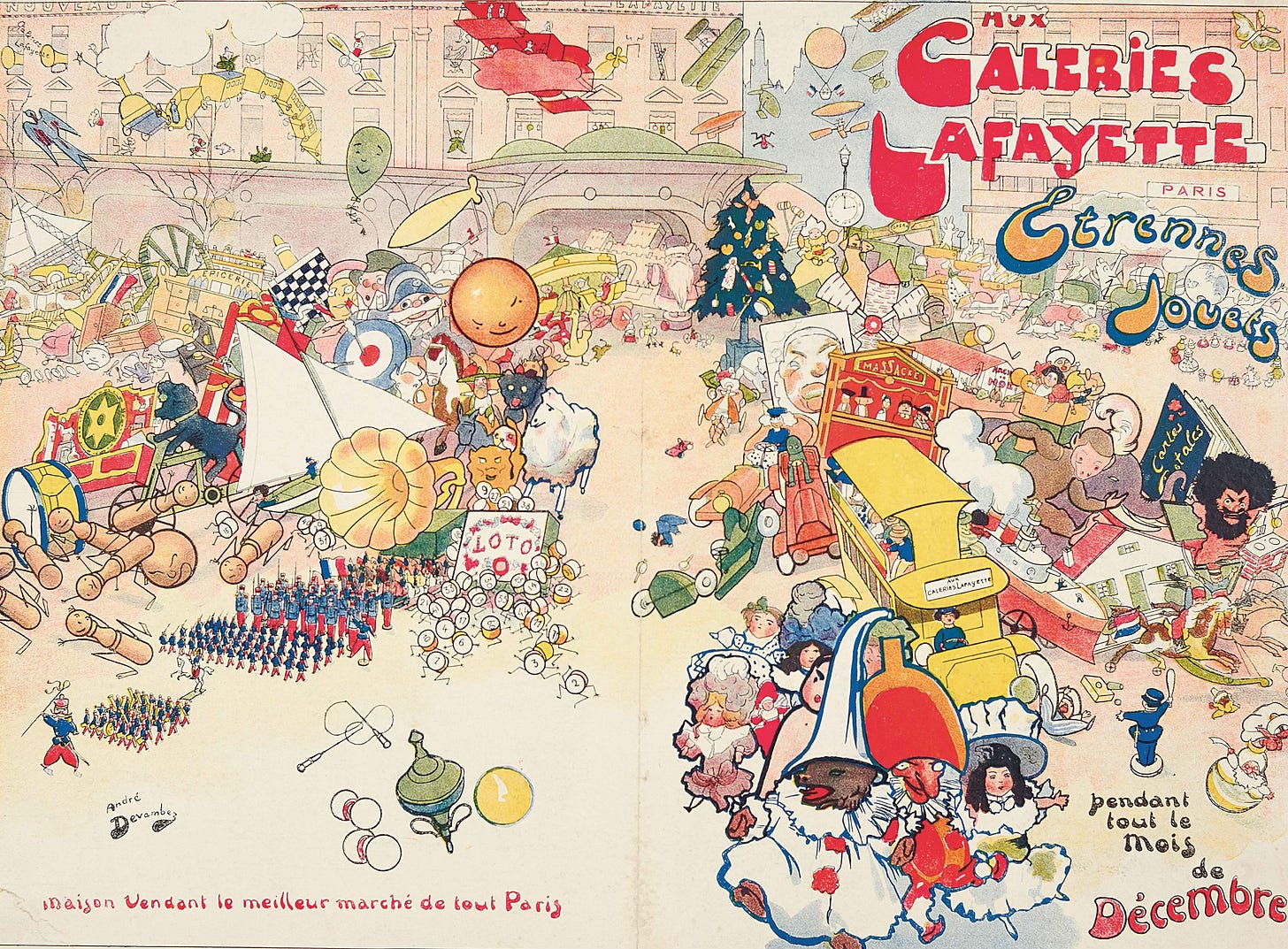

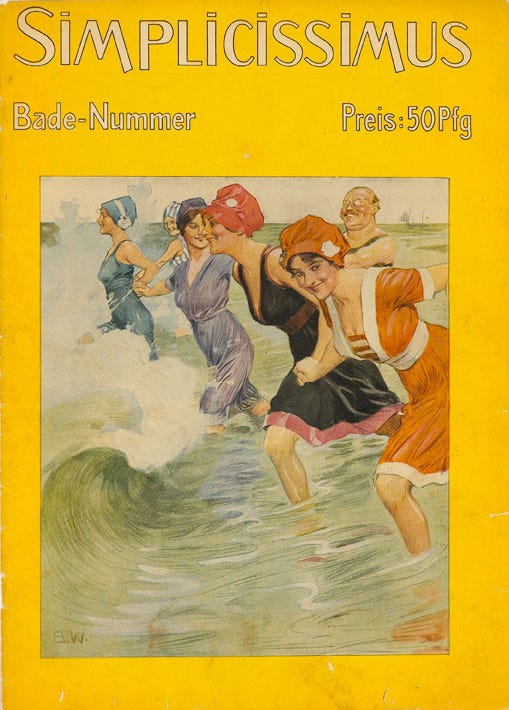

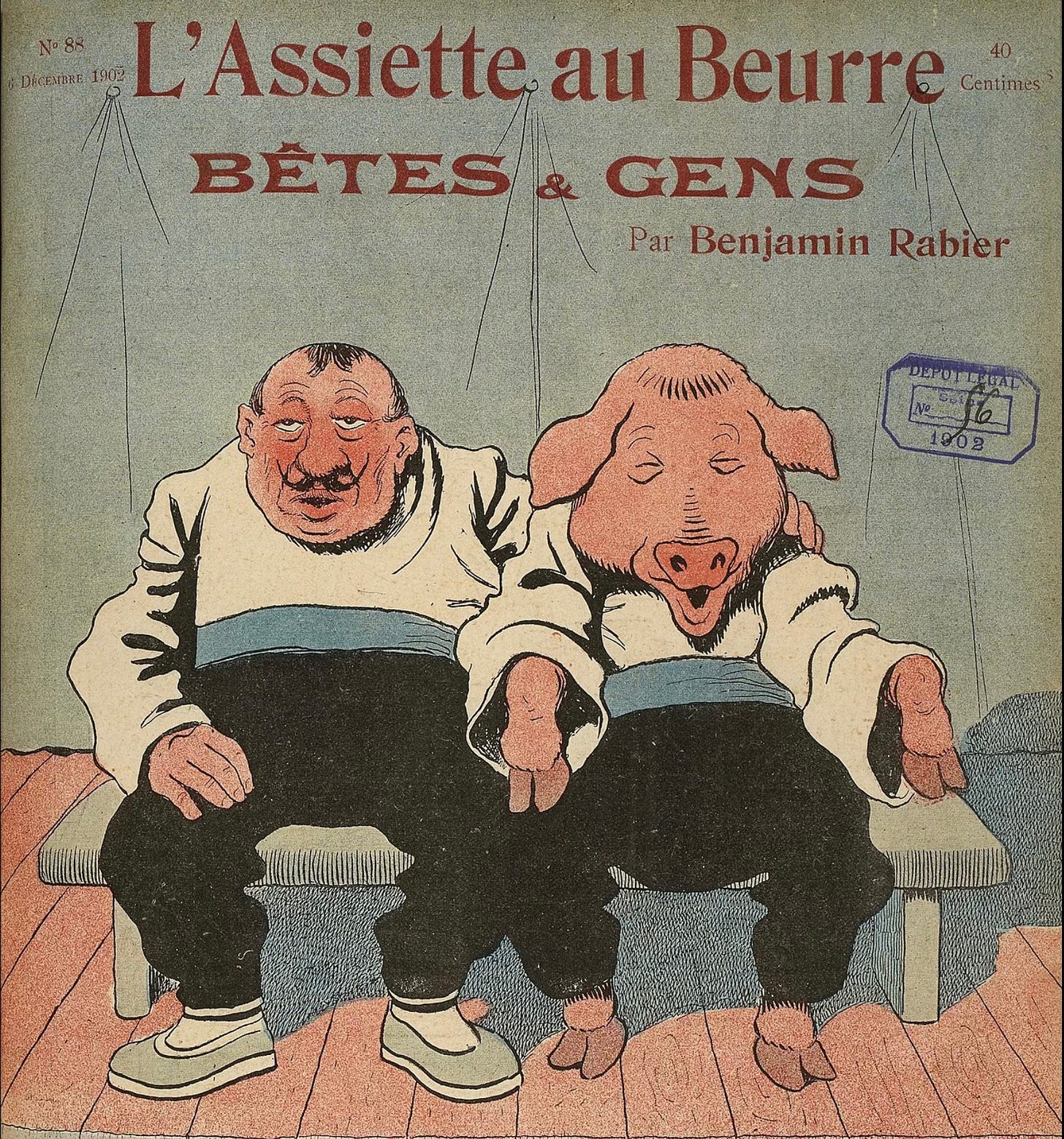

As print media boomed, no longer were news stories the sole focus. Magazines covered a wide variety of topics: gossip, crime, sports, entertainment, corruption, war, romance, celebrities, science, self-help, technology, travelogues, and serialized fiction. Virtually everyone could find their niche interest. Advertisements also reinvented themselves with bold styles to draw in readers. When it came to politics, magazines of liberal, conservative, socialist, anarchist, and other leanings all competed to capture the attention of the growing middle and working classes.

The chaotic rhythm of the vertigo years was created by print media, and the resulting information overload reshaped the public’s relationship to the world. Unsurprisingly, many publishers turned to sensationalism, scandal, and rumors, sometimes outright lying, to bring in readers. It was the “press barons,” British writer J.A. Hobson argued, who were pumping the public with “a continuous stream of false and distorted information.”23 For Austrian critic Karl Kraus, the press did not merely reflect modern anxieties, it manufactured and multiplied them. In 1922, he joked that, “in the beginning there was the press, and then the world appeared.”24 He called those responsible the “journaille” — fusing “journalism” with the French word “canaille” (scum) — to mock their shamelessness. As World World I broke out, he indicted them as responsible for essentially talking themselves into catastrophe.25

Because of the vast readership, mass media during this time openly exploited the emotional state of crowds. As British journalist Francis W. Hirst documented in The Six Panics (1913), calls for emergency and hysteria were a common tool to manufacture public consent. Today, these same strategies are supercharged from the bottom-up. As philosopher Byung-Chul Han writes, the current media environment is like a “dictatorship of emotion” in its ability to torrentially stir up energy and then dissipate practically overnight.26

While the people of the vertigo years certainly weren’t doomscrolling, they were only a degree removed. The sudden avalanche of print media in the early 20th century is the closest parallel to the information overload we are all familiar with online. Its media critics might as well had written their scathing opinions today.

Technological Wonders

The rise of mass media gave the vertigo years their rhythm, but life all around was being quickly transformed. As rural people moved to the growing cities, they were taken aback by the rapid pace of life. Technological advancement was so constant that one could easily convince oneself that society and its morals would someday “catch up.”27

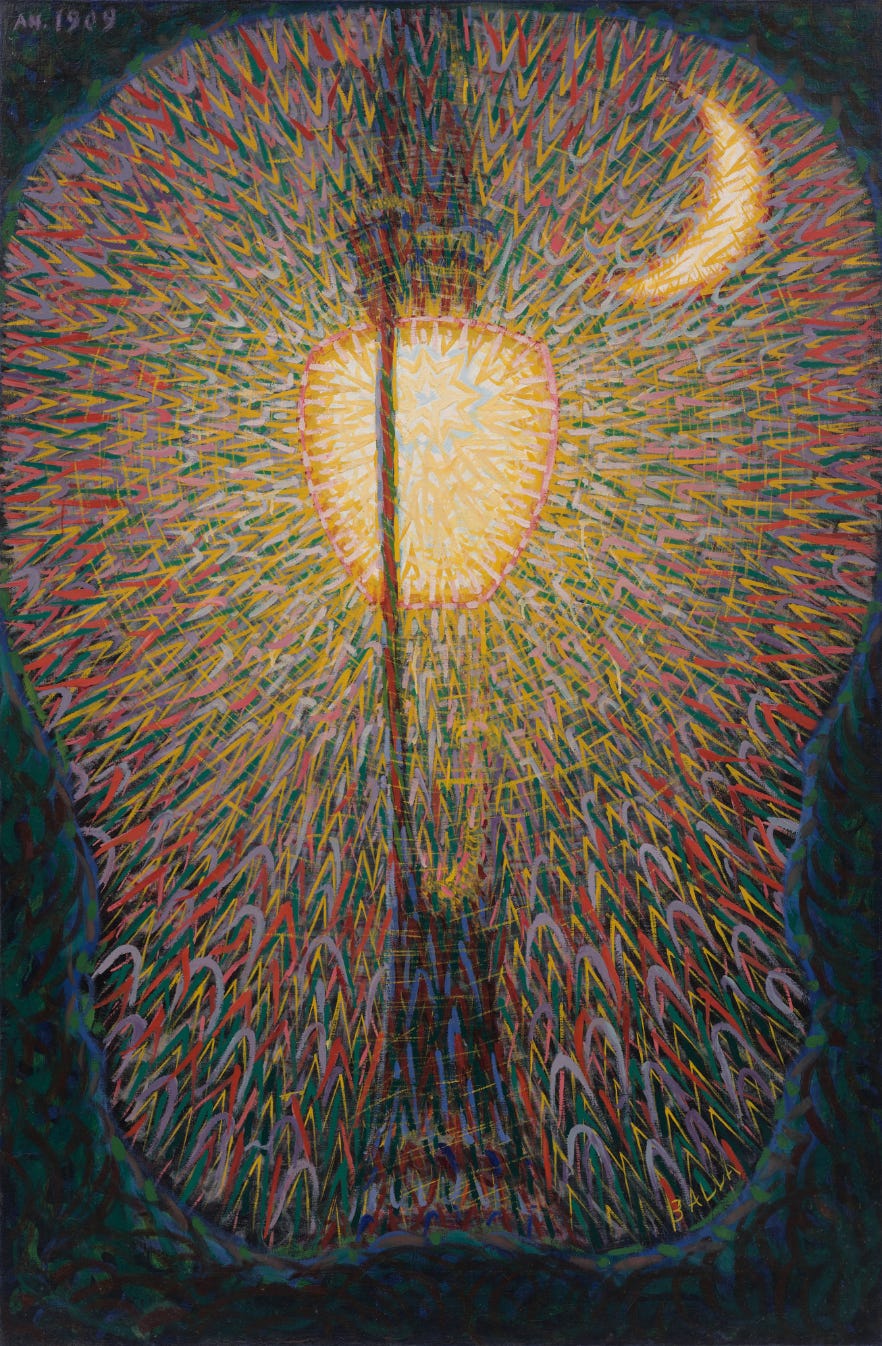

Inventions like the radio, airplane, zeppelin, automobile, electricity, film, skyscrapers, x-rays, and mass transit were all steadily adopted during the early 20th century. Fads even emerged around technologies. X-rays, for example, became a sensation by 1900 with a cult public following.28 Electricity was viewed as magical, even thought to cure all ills. Electrical baths were prescribed to cure ailments from digestive problems to neurasthenia to menstrual cramps.29 Remarkably, virtually all of the futuristic tropes we know of today were already mentioned in fiction by 1914: “ray guns and microfilm, atom bombs, humanoid robots, airships, tape recorders, television, technological warfare, interstellar travel, alien invasions, surviving dinosaurs, faster-than-light travel, and human cloning.”30

The largest European cities had been remade by these technological breakthroughs by 1914. Although it was still early, life was assuming a new rhythm not unlike our own. Speed became the ultimate obsession. “Everywhere life is rushing insanely like a cavalry charge,” wrote French writer Octave Mirbeau, “everything around man jumps, dances, gallops in a movement out of phase with his own.”31 To be modern is to have your mind be “like a racetrack.”32

These paintings and illustrations are just a few examples of how the period’s innovations produced awe. The noise and light filled cities with an altogether different ambiance, inspiring both artists and the public.

A Crisis of Masculinity

Recently, I came across a relevant quote by fellow Substacker

. “The legacy of modernity is as broad as humanity,” he writes, “but recurrent among its outgrowths is the frequency with which men and women renegotiate their relationship to one another.”I think this remains true today. Nowadays, the gender divide dominates the discourse online. Politically, men and women have never been more divided.33 Online communities have formed along gender lines, made possible by loneliness and psychological projection. Again, the relationship between men and women is being renegotiated.

Since there has been so much written on it already, I’d rather not talk about today’s prognosis here. The point being, the vertigo years were also a time obsessed with gender questions. The first-wave feminist movement had started to organize itself and would gain the right to vote in many Western countries by the 1920s. Yet, so much energy was spent provoking questions on masculinity. Machines were taking over from muscle work, and concerns arose over what male virtues would remain in a modern, industrialized society.34 The crisis of masculinity was so serious, some writers argued, that it could supposedly destroy nations if not resolved.

Panic Over Declining Birthrates

Today, worries over a demographic crisis are everywhere. Declining birthrates have become a global phenomenon. Elon Musk has become the most vocal on this question, and often repeats the claim that “civilizational collapse” is imminent if birthrates don’t improve.35 Governments have tried to financially entice couples to have children, setting up entire departments to address the problem. While the global scope of the problem is unique, the same conversation became an obsession in France in the early 20th century.

In 1911, French statistician Jacques Bertillon was preoccupied with a central question: “how can we stop France from disappearing?”36 “Next to this vital question,” he wrote, “all others vanish.”37 For many of its patriots, France was in the death throes of an identity crisis which could threaten its very existence. And with the neighboring German Empire rising in number and industrial power, anxiety pervaded the national conversation. There was a real fear that the French nation could disappear entirely. 1891 was officially the first year that the country registered more deaths than births.38 In 1896, novelist Émile Zola published Depopulation (1896) in which he blamed moral decay as the culprit for France’s demographic decline.

For right-wing French patriots, the demographic crisis was mathematical proof that the virility of the nation had declined. Everything was seemingly at a loss of energy as national confidence suffered. Appropriately, Sigmund Freud chose the Parisians to formulate his early theories on hysteria and neurosis. The environment weighed equally as heavily on sociologist Emile Durkhiem, who wrote Suicide (1897) as if speaking to the French nation itself. The demographic crisis was evidence that something deeper was amiss.

Novels in the years before World War I unpacked the supposed lack of masculinity among the latest generation of boys, told as eulogies of ruined families.39 Fingers were opportunistically pointed at whoever could be conveniently blamed: the decline of faith, social-climbing grifters, a decadent middle class, advertising, the weakened military caste, feminization, capitalism, American influence, Freemasons, Jews, Protestants, and the lot.40 The malaise created a confused, desperate environment that demanded scapegoats.

Cultural Decline (and War As a Solution)

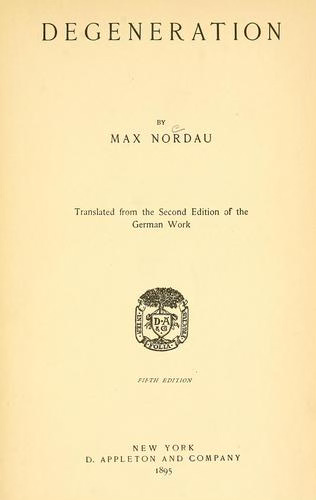

One of the most common themes during the vertigo years was the fixation with “degeneracy.” The loss of masculine energy was obsessively theorized as being responsible for cultural degeneration. This would also become a core tenet of fascist movements in the succeeding decades.

According to these writers, weakness was infecting Europe, morals were dying, and the future would bring collapse if uncorrected. These were the conclusions of Jewish-Hungarian writer Max Nordau’s book Degeneration (1892), which was one of the first texts to describe neurosis. Nervousness, exhaustion, hysteria, egotism, and the inability to act were some of its many symptoms. City life and its decadence had corroded the mind, Nordau argued, and the whole of society needed to be treated like the sick patient it was. It was the decline of “masculine vigor” that had allowed traditions to weaken: men were being “feminized” and women were increasingly becoming “mannish.” This process if left on its own, he predicted, would lead to the “dusk of nations.”41

Nordau would go on to influence other thinkers in Europe, who linked cultural degeneration to the perceived loss of masculine energy. As German writer Otto Weininger argued in Sex and Character (1903), for example, femininity negated culture and was inherently “amoral.” But nowhere else did these ideas gain currency like in France. Having lost the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, French politicians and writers still wrote decades later of the blow to national prestige. Compared to the rest of Europe, anxieties over masculinity reached their most hysterical point in France. As Charles Maurras wrote in La Romantisme Féminin (1903), decadence and romanticism had “feminized the souls and minds of French people.”42 Novelist Maurice Barrès ridiculously speculated that each nation had a set amount of “virility.” Any gain in women’s power would dispossess men of their manhood and produce “half-males.”43

For many of these nationalist writers, the solution simply became glorifying war as a means of renewal. Filippo T. Marinetti, author of the The Futurist Manifesto (1909), famously called war the “world’s only hygiene.” Perhaps war, he thought, could reaffirm masculinity again. The Prussian general Friedrich von Bernhardi similarly believed manhood could only be reinvigorated through war. “War is a divine business,” he wrote in 1911, it was “an indispensable factor of civilization… a biological necessity of the first order.”44 Given that many only knew of war through magazine stories of bravery far away, the outbreak of World War I was initially viewed as a testing ground to redeem lost manhood.

The problem was, nobody truly expected World War I to be as violent, spirit-breaking, and industrial as it was. A decade before World War I broke out, feminist author Rosa Myarender wrote that “modern men are insensitive to the brutality of defeat or the sheer wrongness of an act if it coincides with the traditional canon of masculinity.”45 The traditional canon said that masculinity needed war — but in 1914, it became clear this was not the heroic war men imagined, but death in the trenches for no noble cause.

The World Up for Grabs

In March 2023, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Moscow for talks. Upon bidding President Putin farewell, he told him, “Right now there are changes, the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years, and we are the ones driving these changes together.”46 It was a nod to the plan to reshape the world away from American hegemony that had been dominant since World War II.

At the start of the 20th century, the leading superpower was the British Empire and its currency, the pound sterling, was the strongest in the world. It found itself in direct competition with a rising German Empire, whose growing industry was dominating Europe. The United States today finds itself in a similar position to the British Empire: a rising, industrialized China threatens the U.S. position as the sole superpower. Many have written on the similarities between China and the German Empire’s aspirations under Wilhelm II, even down to President Xi’s obsession with having a world-class navy.47

During the vertigo years, great power politics played as a backdrop to the upending experience of everyday life. For many average citizens, wars abroad were like epic dramas, read with the same intrigue like you would for any good fiction story. Reports on the Boer War (1899-1902) in South Africa, for example, were eagerly read as serialized stories of bravery. However, the period also popularized reporting on social justice, particularly against colonialism. This led to some of the first public pressure campaigns against genocide.48 Diplomatic scandals naturally filled the papers as well, commonly reported like gossip. In one instance, Wilhelm II caused a firestorm in Britain in 1908 when he gaffed in the Daily Telegraph that most Germans hate them (although he clarified that he, in fact, did love British people).49

The whole world was being contested unlike ever before. This is because all the frontiers were now claimed by empires or smaller states. The entire Earth was a closed and integrated economic unit for the first time. Unsurprisingly, the field of geopolitics and global military strategy was invented during the vertigo years. World’s fairs famously emerged as a means to project imperial prestige and culture on this new international stage.50 While citizens then may not have viewed themselves as part of a globalized world, globalization was becoming a reality. The people of this era were the first generation to experience globalization proper, so they were closer to us than we may realize.

New Spheres of Influence

When President Xi made that comment to Putin, he was harkening back to this old form of great power competition when everything was in flux. The 2020s marks its return, and the war in Ukraine was the turning point. It came as a shock to many military analysts who believed a land war in Europe was too costly, strategically nonsensical, and downright impossible to imagine.51 The recent Israeli attack on Iran was equally surprising, only possible because the world map seems open to being redrawn. For today’s great powers, the goal is consolidating their spheres of influence, often along cultural lines. Russia has staked its claim, China has yet to stake its properly. Trump, likewise, has laid claim to Greenland and the Panama Canal, as well as jokingly to Canada, whose land he views as fitting “beautifully” on a map in a fully-realized North American union.

We are no longer living in a world situation resembling the Cold War. That was a battle between two ideologies that each claimed to want the entire world, either as liberal-capitalist or communist. Such dreams are long dead now. Trump’s transactional approach to politics and diplomacy is fitting for the new vertigo years. Journalist Edward Wong has speculated that Trump views an agreement between Russia, China, and the United States on their respective spheres of influence as the “ultimate deal.”52 Trump may not know it himself, but his approach is very much in line with thinking “we haven’t seen for 100 years.”

An Unsettled Feeling

Writer Lauren Berlant has argued that in times of social upheaval, people often find themselves desiring something that is actually an obstacle to their flourishing. She calls it a form of “cruel optimism.” In her 2011 book of the same name, she explains how politics can often take the form of cruel optimism. In times of great change, political desires happen at the affective, pre-reflexive level: anxieties are first formed, often without having an “explanation.” This causes individuals and crowds to irrationally desire some action, so they can finally transform that unease into something they can identify.

You are “optimistic” because you know the pace of change will continue — but it is “cruel” because it is incompatible with your own flourishing. There is a mismatch between desire and reality. The early 20th century was a period of cruel optimism, a time of deep emotion desperately looking for reasons. People’s various desires were often incompatible with the actual trends of modern life. This helps to explain why they talked themselves into a catastrophe.

The vertigo years feel so familiar because accelerating change provokes a strong emotional response. Today, we are also wrestling with a form of cruel optimism: too much emotional affect, but the speed of social change makes it difficult to make sense of it. That which we desire, like autonomy or community or security, are made impossible by the very technological systems we use everyday. By lacking the language to understand that which we experience, we feel a sense of vertigo. What’s left is a collective, unsettled feeling that lashes out as a false means of understanding. Technology may be improving, but it is “cruel” in the sense that it prevents understanding, until emotionality forces a response by chipping away at us until we finally break down.

To read about the vertigo years is to read of a period teetering on the edge. But despite its dark undercurrents, it was an unparalleled time of creativity that still reads fresh. I’m sure there are more similarities to our own time than the ones I’ve covered here. The vertigo years saw the birth of that modern feeling, which was described most beautifully by philosopher Marshall Berman: “to find ourselves in an environment that promises us adventure, power, joy, growth, transformation of ourselves and the world—and, at the same time, that threatens to destroy everything we have, everything we know, everything we are.”53 The new vertigo years today are motivated by this same tension.

The idea of accelerating change and exponential growth was first theorized in the early 1900s.

The vertigo years (1900-1914) overlap with two other periods commonly mentioned by historians. Fin-de-siècle (“end of century”) is used to describe the late 1890s and early 1900s. It is associated with ennui, cynicism, and decadence. More broadly, the period known as La Belle Époque (“The Beautiful Era”) was between 1871-1914. The title was coined after WWI by those who looked back nostalgically.

“Sleepwalking” was a common theme used by writers to describe the years leading up to World War I. Hermann Broch used it as the title of his 1930 novel, where he explores the lives of three individuals before 1918.

Marjorie Perloff. On the Edge of Irony: Modernism in the Shadow of the Habsburg Empire (2016), pg. 95.

Philip Blom. The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 276.

The rise of mental illnesses particularly affected the professional classes. “Overwork” was a common complaint which demanded “rest cures.” Patients in mental hospitals also rose drastically. In Germany, they increased fivefold between 1870 to 1910, as per Blom (pg. 268).

The early 20th-century saw breakthroughs across many different areas of culture. It was thought rational explanations of the were no longer satisfactory, so artists explored uncharted areas. Futurists painted the world by imagining technological speed; composers introduced harsh atonality; art nouveau became a popular ornamental style; and modernist novels probed the dark underbelly of the mind with fragmented, stream-of-consciousness writing.

Hugo von Hofmannstahl. “The Affirmation of Austria” in Hugo von Hofmannstahl and the Austrian Idea (2011), pg. 57-59.

As philosopher Byung-Chul Han told Noema Magazine in an interview, “Information goes along with fundamental suspicion. The more we are confronted with information, the more our suspicion grows.”

Volker Rolf Berghahn, Imperial Germany 1871–1918 (2005), pg. 185–188.

Paul Manning. News and News Sources: A Critical Introduction (2001), pg. 83.

One victim of the conversation just days before the total mobilization of World War I was French pacifist Jean Jaurés. He was killed by a fanatic who was so “moved by op-eds” that it drove him to murder.

Novelist Stefan Zweig recounted in The World of Yesterday that many foolishly felt that the “technical progress of mankind must inevitably result in an equally rapid moral rise.”

The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 75.

The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 87.

The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 88-89.

The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 256.

The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 256.

The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 179.

The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 5.

The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 5.

The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 13.

The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 17.

The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 15.

The Vertigo Years (2008), pg. 188.

Journalist E.D. Morel and diplomat Rodger Casement led the public outcry against genocide and slavery in the Congo Free State in 1904/1905. They are considered the pioneers of international human rights investigations.

In 1908, The Daily Telegraph published “The German Emperor and England: Personal Interview” which caused a major scandal.

With Saudi Arabia’s World’s Fair 2030, this is now making a comeback in a big way.

Marshall Berman. All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity (1982), pg. 15.

Great stuff to help me fathom the state at which we are in.

We have the technology and resources to run things beautifully.

But still war persists. Corruption persists.

When will humanity make the choice for truth?

Can we handle the truth?

Can a doctor know that he's been injecting toxins into people for decades and be ok with it?

I heard an interview with a neuroscientist that said when he got into graduate school in the 90s, they thought the study of consciousness was not worth it.

Wow, 3 decades ago, scientists of the brain thought that consciousness was something dumb?!

In my years I would see the future as either scary or great. Heaven or hell.

These days, I just see an absurd future. Is that me giving up?

I suppose it is because like you and others here, we have seen times when humanity said one thing and did another.

I hope this time with the study of consciousness in mind we can prevent further insanity.

It's been insane enough for decades.

An excellent article. Although a student of history, I never really drew these parallels with our time, but it makes sense. The speed of technology and its effects on humankind need to be consumed at arm's length to lessen some of the disorienting pulses it unleashes. I find some solace in the fact that the smart phone generation, in now becoming parents, seem to be rebelling a bit at the speed and the influence of changes that the internet and social media has wrought. AI now confronts us with the potential for tectonic changes that seem to echo the same things felt during these vertigo years you have so eloquently described. I am writing a piece about defining our humanness now before AI invades the realm of our self formed reality. I have a better sense of why I was moved to begin writing it.