How the Locomotive Became a Metaphor for Modernity

At the turn of the 20th century, many different ideologies tapped into the locomotive as a metaphor in a struggle over the soul of the modern world.

Wow, so many new readers. Thanks so much for subscribing. I’ve been away for some time due to personal matters, but happy to say I’m back to writing consistently to this small corner of the internet. This one’s part of my Past as Prologue series.

In the past month or so, I’ve been on a kick reading about modernity and what it really entails. My last essay discussed a few early modernist writers, and how their words relate to the lived experience of far more people today than ever before.

In my view, thinking of the present this way gives it the weight it deserves. And since I like writing pieces in conversation with past ones, I wanted to continue this thought, but from a different angle.

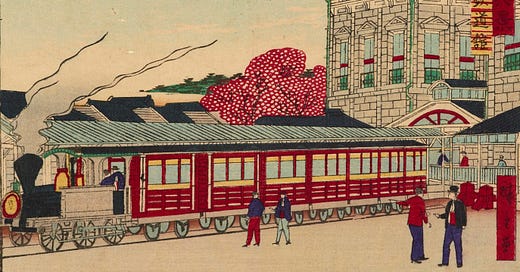

If there’s an image most associated with modernity, it’s likely the locomotive. The train and railway have so often been the leading motif of modern culture. For countless political movements, writers, artists, engineers, scientists, and the like, the locomotive was viewed as the spiritual engine of the times. The main attraction toward it was its speed, which was thought to embody that relentless push forward so characteristic of modernity.1

The symbolism behind the locomotive has since lost some of its power, but in the early 20th century, it truly was everywhere. One can understand modernism just by following it across many different contexts. Italian futurists, for one, commonly evoked it to illustrate the momentum that would power their machine worlds. In another, completely different context, the locomotive became synonymous in the Soviet Union with history’s march forward.

The diverse use of the locomotive as an idea reveals what was actually at stake: it was effectively a battle over who could lay claim to modernity. The locomotive was not just about speed and industry. It was also about everything else, all at once: mass politics, history, and the imaginable future. The stakes could not have been higher, and countless died for them.

For this piece, I have collected literature and images relating to the locomotive as a metaphor. Through these historical artifacts, there is a story to be told of how an industrial machine was elevated into a representation of modernity itself. Perhaps by recounting such a history, we can better frame our own modern present and the energy that animates it.

A Story of Modernity’s Casualties

It's easy to imagine why the locomotive spoke so directly to ideas of progress and its movement. It annihilated distance and allowed for an unprecedented opening up of the world.2

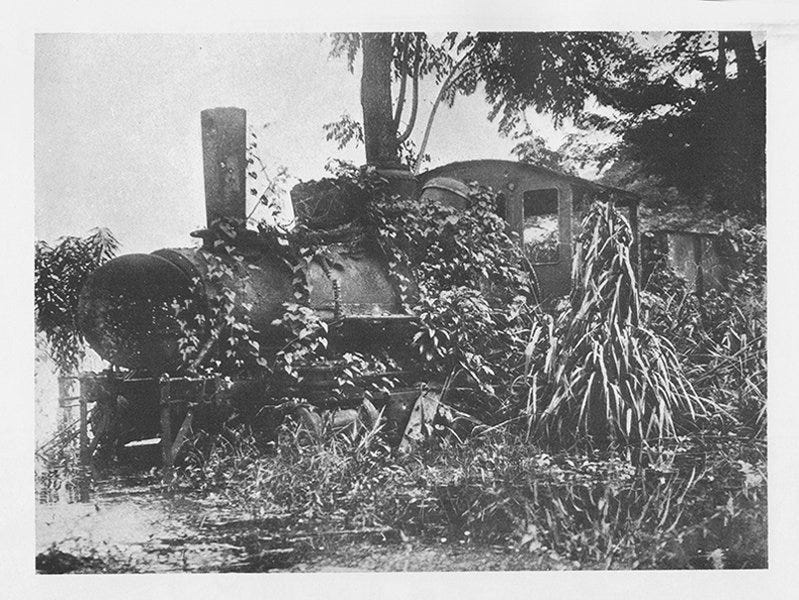

Still, the early railroad was equally as representative of that ugly underside of modernization. Amid all that unparalleled potential also came great loss. In this way, the locomotive embodies the core contradiction of modernity. It is a story of modernity’s tragedies as much as its dynamism.

The first causality was the pastoral, and many early 19th-century artists found the machines to be ugly and destructive.3 Writer John Ruskin lamented that “you can’t have art where you have smoke.”4 And poet William Wordsworth likewise found them “at war with old poetic feeling.”5 These objections may sound dated now, but they were put forward by a handful of artists and critics with luddite sympathies.

Still, these romanticized upper-class fusses were some of the weakest objections. In reality, it was people themselves who often found themselves in the way of the railroad and modernization. In the United States, it resulted in the importation of an underclass of exploited, immigrant labor; military encroachment on Native American lands; the near killing off of the American buffalo; the polluting extraction of coal and other resources; and thousands of on-site deaths which were never reported.

A similar tragedy unfolded in all corners of the world as empires industrialized themselves.6 One of the most moving illustrations of this sad reality came from Czarist Russia in the heavily-censored poem The Railway (1864) by Nikolai Nekrasov. Its influence was so lasting that a common connotation for the word "train" in Russia in the mid-to-late 1800s was "death."7 The poem recounts the tens of thousands who perished building the Russian railway, their souls singing as the train passes, and how "all along it there are bones, Russian bones..."8

By the late 1800s, railroads became bogged down in scandal after scandal. In the United States, the public openly asked to be saved from railroad monopolies.9 Critics contended that the speculative frenzy bred monopolistic corruption. In 1881, H. D. Lloyd wrote in The Atlantic that we must affirm that “the nation is the [real] engine of the people,” not the locomotive.

In less than the ordinary span of a lifetime, our railroads have brought upon us the worst labor disturbance, the greatest of monopolies, and the most formidable combination of money and brains that ever overshadowed a state.10

Many worried the railroad tycoons had grown so large that they were holding the state hostage, steering its power solely for their interests.

By the turn of the 20th century, a prevailing opinion was that the locomotive was not working toward what people expected of modernity. To somehow “reclaim the engine” thus became a thinkable concern. On this point, I have to return to Nekrasov’s poem The Railroad (1864). It hints at something which would later be a core trope of modernism.

As I already said, the poem laments the Russian peasants who died building the railroad. Yet, it also affirms the actual creator of the railroad as being the people themselves. There is this hope that someday they will harness this power to build a new road for themselves into “wonderful times.”11 In fact, the poem was one of the first to affirm industrial power as the "creative work of the people."

This transformation of the locomotive—from its initial association with domineering big business into a vehicle of popular creation—would push it into mass culture and politics. The locomotive as a metaphor took on new life in the early 20th century as it became intertwined with what people desired modernity to be.

The Locomotive Joins Mass Society

In the preface to The City of Tomorrow (L’Urbanisme), the famous architect Le Corbusier recounts how a vision of modernism came to him suddenly while walking down a Parisian boulevard in 1924. Frustrated and dodging dangerous traffic, “it was as if the world had gone mad” when just 20 years ago, “the road belonged to us then."12

Yet by the end of the passage, a reversal comes to him. Rather than fight the traffic, Le Corbusier instead gives in and fully identifies with it. He takes a symbolic leap and, as if speaking for industry itself, he realizes “the simple and naive pleasure of being in the midst of [such] power."13 He writes, "one participates in it, takes part in the society that is just dawning. One believes in it.”14 At this moment, Le Corbusier learns to speak from the perspective of the locomotive itself.

Le Corbusier was no revolutionary. In fact, he saw this revelation as a way to create industrial mega-structures that would calm mass political zeal, not amplify it.15 Still, this short passage illustrates the transformation of the locomotive as a symbol. Culture began to reflect on the idea that modernity and its locomotive were not outside us, but rather one with "the people."

The ideological battle over who would control the metaphorical engine took shape in the early 20th century. Represented in a variety of contexts, each tells us much about the various contours of modernism.

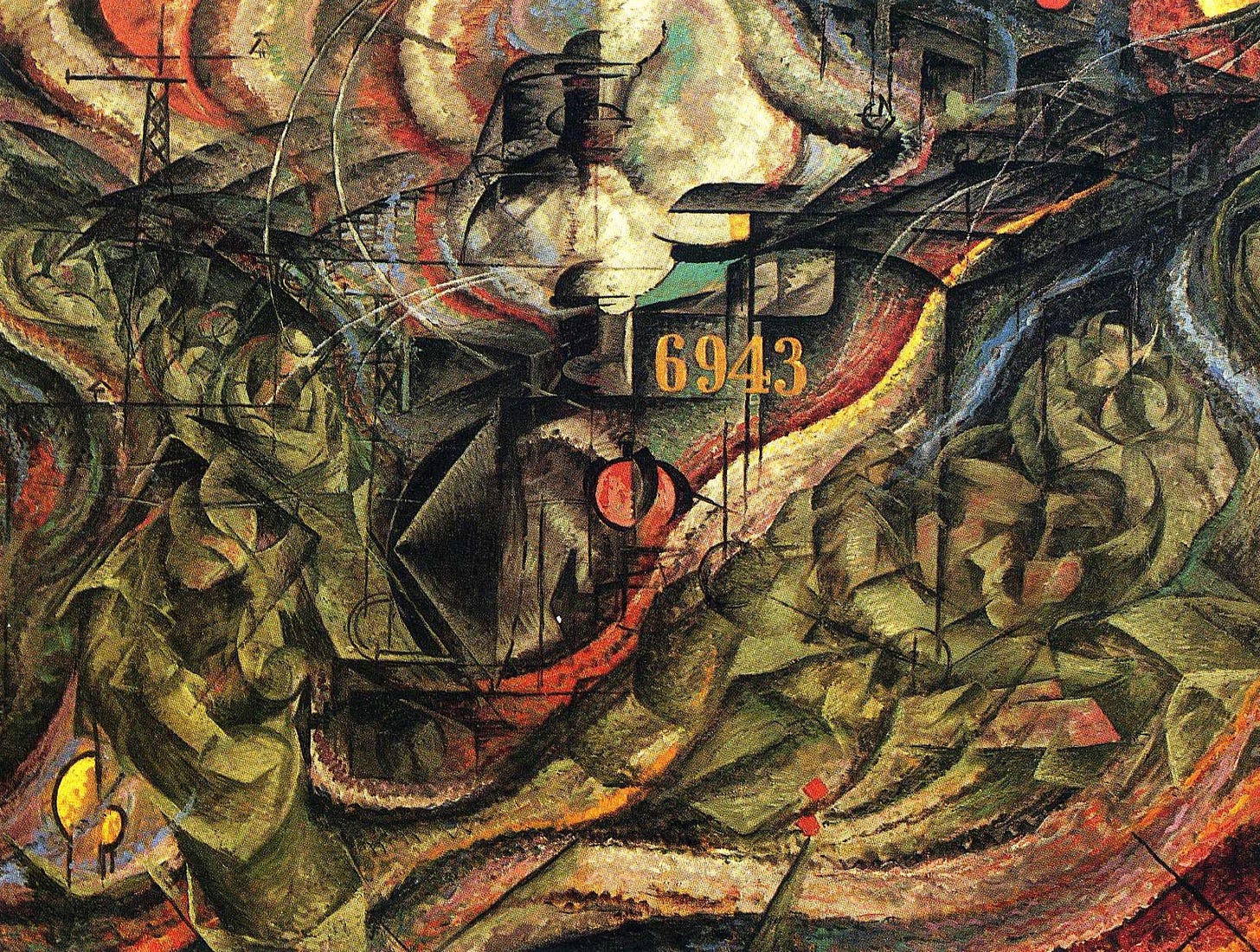

The Locomotive As Modernist Art

One group particularly entranced by the locomotive and machinery was the early Italian futurists. World War I was viewed as a way to live out this artistic desire in all its variety. In a 1914 letter, founder of the Futurist Movement Filippo Marinetti wrote to the artist Gino Severini:

I believe that the Great War, intensely lived by Futurist painters, can produce true convulsions in their imaginations… [Boccioni, Carrà and myself] urge you to interest yourself pictorially in the war and its repercussions in Paris. Try to live the war pictorially, studying it in all its mechanical forms (military trains, fortifications, wounded men, ambulances, hospitals, parades etc.).16

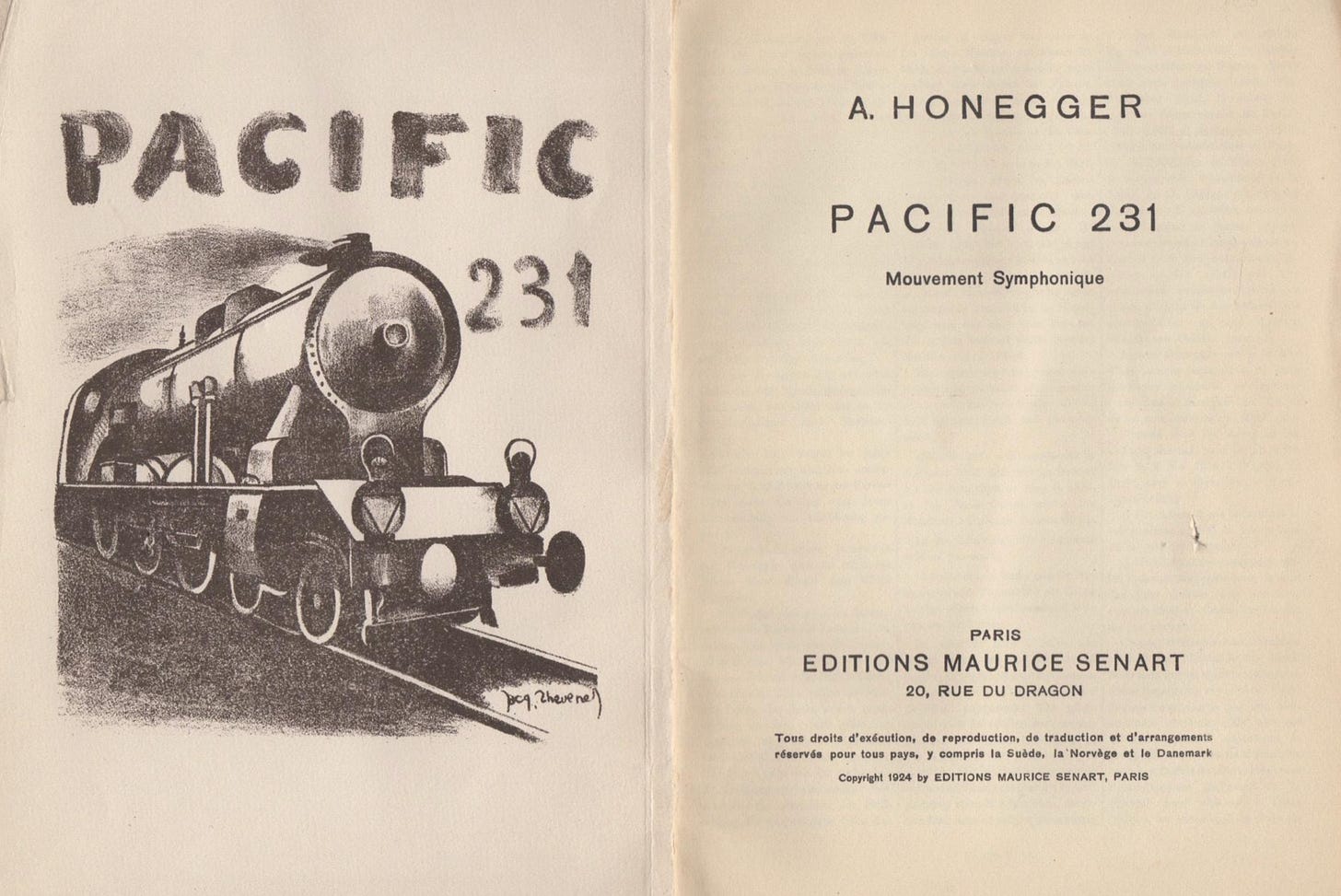

The bellowing sounds of locomotives also found themselves in modernist, musical interpretations. In Pacific 231, conducted by Arthur Honegger, an orchestra interprets the sounds of a locomotive accelerating, moving at top speed, and finally coming to a stop.

The Locomotive as Imperial Aspiration

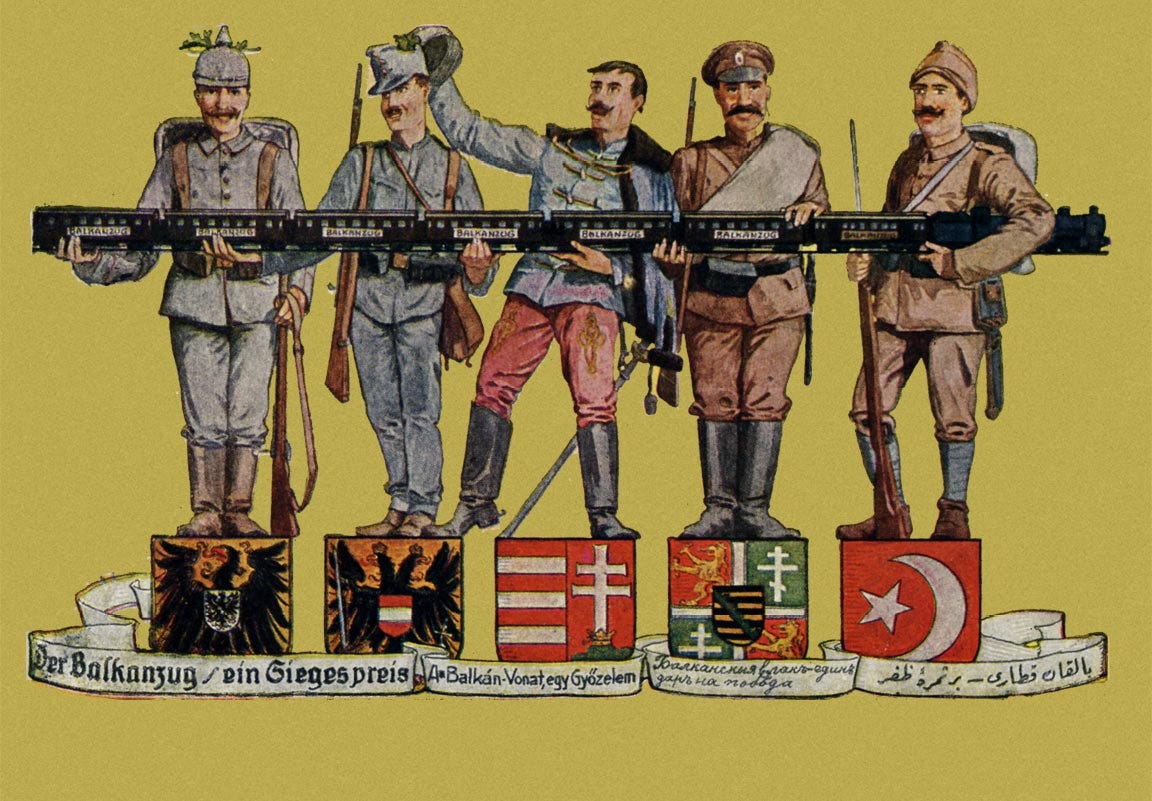

Aside from art, the locomotive was widely utilized by imperial states to plant a flag in the new order they hoped to build. States attempted to embody their people through the locomotive. Emergent empires employed “propaganda-trains” and used their railways to project unity within their dominion in a time of great upheaval.

Balkanzug was one such propaganda-train for the German Empire during WWI.

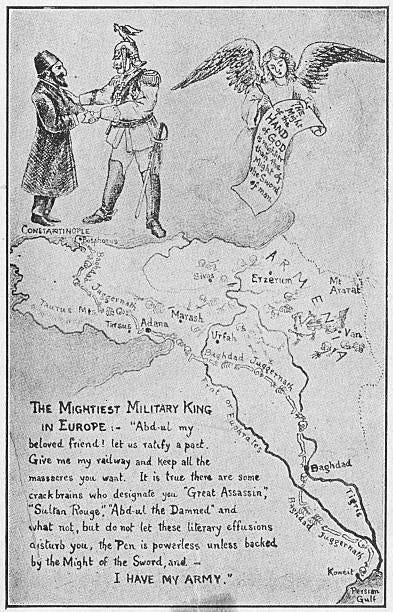

Before the Balkanzug, there was also the proposed Berlin-Baghdad railway that caused a scramble among the great powers. It never served to be a propaganda-train, but was one of the major provocations leading up to World War I.

The railway was heavily symbolic because it tacitly signaled to the Ottomans that there was German support for “a jihad to liberate all Muslims under British domination." "The result would be a world where Islamism and a German empire would peaceably blend.”17 The Ottomans entered World War I on such conjectures.

The Berlin-Baghdad railway was an attempt by the Ottoman Empire to catch up to European powers, but there was another more successful one. Now forgotten, the Hejaz Railway was the last projection of Ottoman power that truly shocked European empires before World War I. It became fully operational in 1908.

The massive project was steeped in metaphoric importance. The railway would unite all of Islam behind the Ottoman state by constructing a long line between Istanbul and the holy site of Mecca. It was intended to pacify the rising tide of nationalism with Islamic unity through industrial might which ultimately failed.

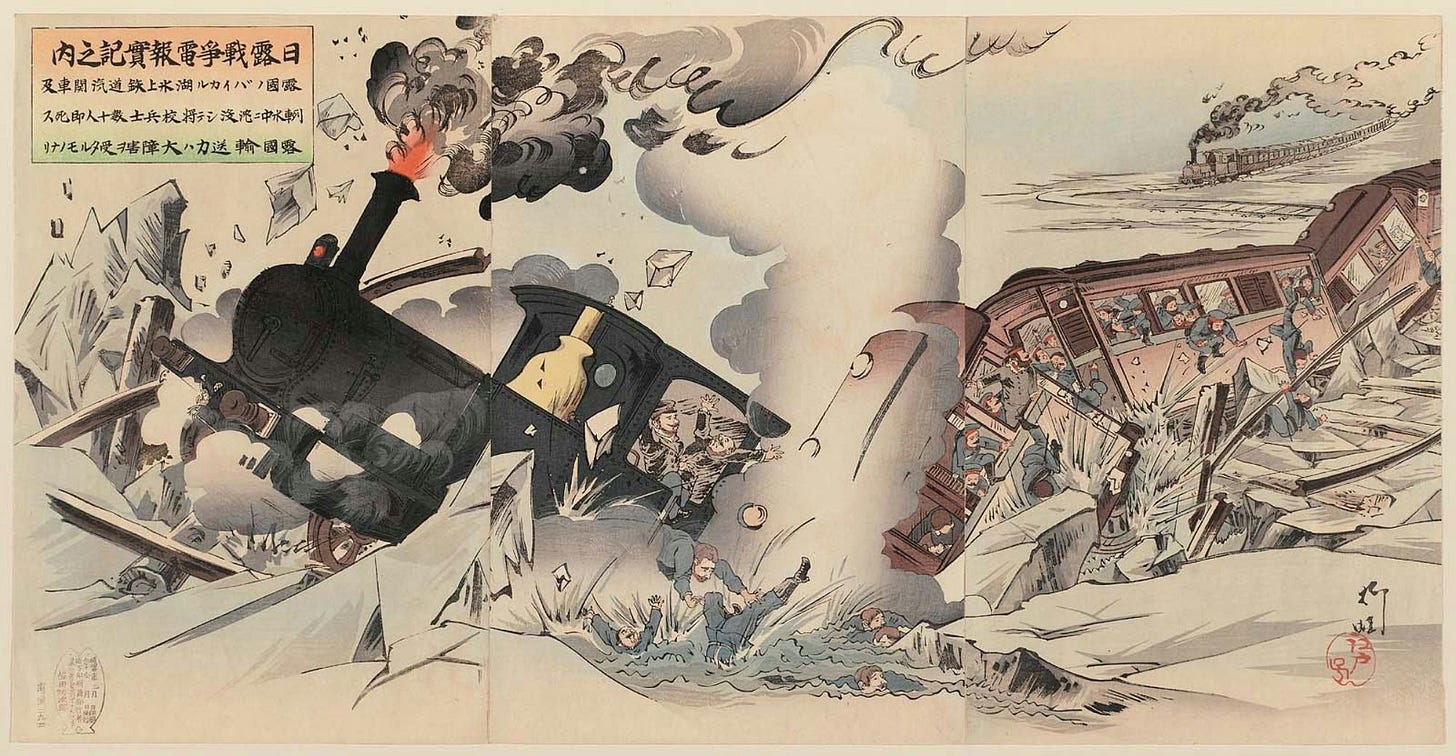

In East Asia, Imperial Japan extensively used the locomotive as an idea to project cultural power. It was a core component of the state’s modern mythos. Disputes over the critical Chinese Eastern Railway led to a war with Russia (1904-1905). It ended with an industrialized Asian power decisively defeating a European one for the first time in history. The railway war prize was renamed the South Manchuria Railway.

The railway was heavily publicized both as a testament to Japan’s modernization of Manchuria and as a thread that tied together all the peoples under its dominion. When Japan left the League of Nations in 1932 after its invasion of Manchuria, the South Manchuria Railway was sent to Chicago's World Fair (1933-1934) to demonstrate the progress it would bring to the newly-occupied region.18 The railway corporation was also active in the financing and production of films, releasing over 200 titles.19

Communism Claims the Locomotive

Communists were especially attached to the locomotive as a metaphor, particularly as a means for understanding history. This turn of phrase was originally established by Karl Marx in 1850 when he wrote that “revolutions are the locomotives of history.”20

Within Marxism, there was this belief that revolutions tore the very fabric of social reality. Philosopher Walter Benjamin likened it to “blasting open the continuum of history.”21 The locomotive's speed could not be more fitting for this millenarian view. Marxist commentary before and during the interwar years consistently debated the locomotive metaphor — if it was moving too quickly, what were the tracks, what was being left behind, and where it was even going.

In The Russian Revolution (1918), Rosa Luxemburg criticized the 1917 October Revolution in these terms—the locomotive had not gone far enough.

The “golden mean” cannot be maintained in any revolution. The law of its nature demands a quick decision: either the locomotive drives forward full steam ahead to the most extreme point of the historical ascent, or it rolls back of its own weight again to the starting point at the bottom; and those who would keep it with their weak powers half way up the hill, it drags down with it irredeemably into the abyss.22

Others considered that, perhaps, the locomotive was momentarily not in step with communism. In 1933, Leon Trotsky remarked that “fascism, it seems, has unexpectedly become the locomotive of history.”23

But the locomotive was not just figurative for communists. It was also an actual, physical entity capable of circulating ideology. From the very beginning, the motif of the locomotive cemented itself in the Soviet mythos with Vladimir Lenin’s return to Russia, arriving at Finland Station in April 1917. Both this train and the one that later carried his casket around the Soviet Union were the only two locomotives preserved by the state.

During the Civil War (1917-1923), locomotives wielded immense cultural power which was projected throughout the entire country. The metaphor broke into everyday life as the Bolsheviks constructed “agit-trains.” They were tasked with broadcasting the forces of modernization to the rural peasants of Russia. The most famous of the trains, October Revolution, served some 12 tours between 1919-1920.

Agit-trains were typically made up of 16 to 18 cars and screened cinema. They were also equipped with “broadcast radio stations, telephones, mobile camera shops, printing presses, and newspaper offices.”24 In two months alone, the October Revolution screened cinema to over 100,000 people in 97 sessions. Other agit-trains included Red East, Soviet Caucasus, and Red Cossack.

The purpose of the agit-train was to bring modernity right to the periphery with all the newest mediums. Many peasants undoubtedly imbued such experiences with religious connotation, as if something holy had entered their provincial space. Thanks to their novelty, the trains proved to be quite popular as a social phenomenon.

The locomotive as a metaphor reached its most ideological form in the Soviet Union. But the modernist novelty of its beginnings was patently ruined as it regressed into viewing its conductor as a single individual. On his sixtieth birthday in 1939, Stalin was given the singular title of “the great driver of the locomotive of history.”25 The locomotive as a metaphor for history transformed itself into a metaphor for a cult of power.

The Metaphorical Train Departs

I close here at the end of this journey, having passed through many of the contours of early 20th-century modernity — from art and futurism, to imperial statecraft and war, to communism and the march of history itself. Providing us with a panoramic view in all its variety, the locomotive as a metaphor is inseparable from the drama of modernity.

Still, the idea rears its head today. It remains a core feature of Chinese socialism, both as a domestic representation of its industrial dominance and as geopolitical tactic. President Xi continues to use the 20th-century language of the “locomotive of history.” Amid the war in Ukraine, locomotives have also once again become choke-points with grand geostrategic significance.

While the train has definitely not left us today, the metaphor arguably has. The late Mark Fisher described the contemporary undercurrent as the “slow cancellation of the future.” The past few decades have seen a major decline in large-scale public projects, especially in the United States. The vitality that would power the locomotive metaphor into our current modernity has run out of steam. Many feel like the spiritual, creative well is running dry.

Some might contend that the locomotive metaphor was a spoiled one of hubris from the start, for mastery over nature is fundamentally misguided. But really, those that historically abused the metaphor in this way were the misguided ones. I would rather view the symbol as the explosive consolidation of human potential.

The idea behind the locomotive is so easily transferred over to the internet’s capabilities today. And in a time when narratives of meaning have collapsed, a comparable catalyst is certainly bubbling under the surface somewhere. My own opinion is that I am a believer in the spontaneous crowd and historical dynamism always returning. As I mulled over in my last piece, it could be that modernity is now picking up steam again.

This sentiment has been expressed today as well, and the desire to speed it up further is frequently called accelerationism.

One of the conditions of modernity is “space-time compression” or the “annihilation of space through time.” As capitalism develops, it further shrinks the time required for distances to better integrate itself into a global market whole.

Wojciech Tomasik. The Railway in Communist Symbolism (2002), pg. 61. [https://repozytorium.ukw.edu.pl/bitstream/handle/item/5218/The%20Railway%20in%20Communist%20symbolism%20Some%20observations%20on%20Soviet%20and%20Polish%20art.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y]

Tomasik, pg. 61.

Tomasik, pg. 61.

One of the best sources documenting this history is historian Eric Hobsbawm’s Age of Capital (1848–1875). Part II has a long section titled “Losers” which documents the casualties.

Tomasik, pg. 63.

Tomasik, pg. 63.

Marshall Berman. All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity (Penguin: 1982), pg. 165.

Berman, 166

Berman, 166

Berman, 166

Marylaura Papalas. Speed and Convulsive Beauty: Trains and the Historic Avant-garde (2015), pg. 7 [https://newprairiepress.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1818&context=sttcl]

Tomasik, pg. 77.

Thank you, just what I needed to read right now, as I've had a blues refrain stuck in my head. That the train in the blues is a metaphor for spirituality, a better life, or a life passing by, all of this of course so well encapsulated in machinery (the deus ex machina or literal engine).

The idea of the powerless projecting onto technology a kind of power, well, that could be wrapped up in Mark Fisher's slow cancellation of the future: who is the locomotive pilot in such a future?

Amazing photos and such a great read.