Some years ago, I had the pleasure of reading The Hedgehog and the Fox by Isaiah Berlin. I often recollect a short passage from it on causality and history.

The passage was on writer Leo Tolstoy and how he was suspicious of those who “posed as official specialists in managing human affairs.”1 What leads to a chain of events and what follows is inherently unknowable. A single individual is therefore not wholly responsible for that which moves history. Tolstoy would have said, "only the unconscious activity bears fruit, and the individual who plays a part in historical events never understands their significance.”2

I mention this because the past decade, especially the past few years, has been closely tied to an unraveling of expectations. That is to say, we have come to expect some chaos or at least more unpredictability than usual. Our bias to normalcy that we enjoyed since the 1990s has been shaken. Today’s historicity can maybe best be summed up as a mixture of shock, surrealism and bewilderment. How many times I’ve heard the line, “can you believe it?” Too many.

Someone who has taken the future’s erratic prospects as particularly worrisome is former Armenian President Armen Sarkissian. He spoke about it candidly at the 2020 Munich Security Conference. It was becoming increasingly difficult to predict social outcomes with any certainty. Social systems are so complexly entangled today, it is making them more chaotic. A trained physicist specializing in computer modeling, Sarkissian is no stranger to randomness within systems. It is from this vantage point that he calls today’s social sphere ‘quantum-like.’

The quantum-like element that Sarkissian was describing is the public, made up of individuals who are bouncing around multi-directionally within a convoluted system of interrelations and nested groups. Politics, in our digital century, has thus been transformed. Its unpredictability, buttressed by technology and the infosphere, is one of the main drivers of history today.

The future was never really predictable, but it is arguably now harder than ever to make a frank assessment of what’s to come.

Politics? Meet Quantum Mechanics.

It’s always dangerous when someone who does not possess a scientific background borrows its concepts for explanation. I’m obviously not a physicist. Still, I believe Sarkissian is onto something. Quantum mechanics can serve as a useful metaphor for understanding the social sphere. Unsurprisingly, there’s recently been a surge of interest in the so-called “quantum social sciences.”

Quantum theory deals with the ‘world of the very small.’ One of the main takeaways of this world is that, on the subatomic level, one cannot ascertain where the quantum entity is and where it is going at the same time. If you try to apply deterministic and continuous frameworks, you will not grasp it. Obviously, quantum mechanics do not influence historical forces directly. Still, as a metaphor, it can be useful as a means of understanding our current social environment.

In social processes, the “world of the very small” is individuals who are connected by a networked web of relations. The complex chain of interactions is unknowable, but nonetheless produces large-scale effects. These individuals seldom know what their end point is. Their main drive seems to be motivated by dissatisfaction in most cases. It is the ‘energy” that jolts everything when it reaches critical mass.

Sarkissian mentions the 2018 Armenian Revolution as an example:

The example that I brought to you, over the revolution in Armenia, is a classical fusion of elementary particles. You have plutonium or uranium which is of a specific mass… you need just a couple of high-energized particles. They come and hit. And what you get is a chain reaction. The same is happening in a human system.

In the social society [of Armenia], that specific mass [was] of unhappy people… Highly-energized, ten young men, no ideology nothing, just talking about unhappiness.

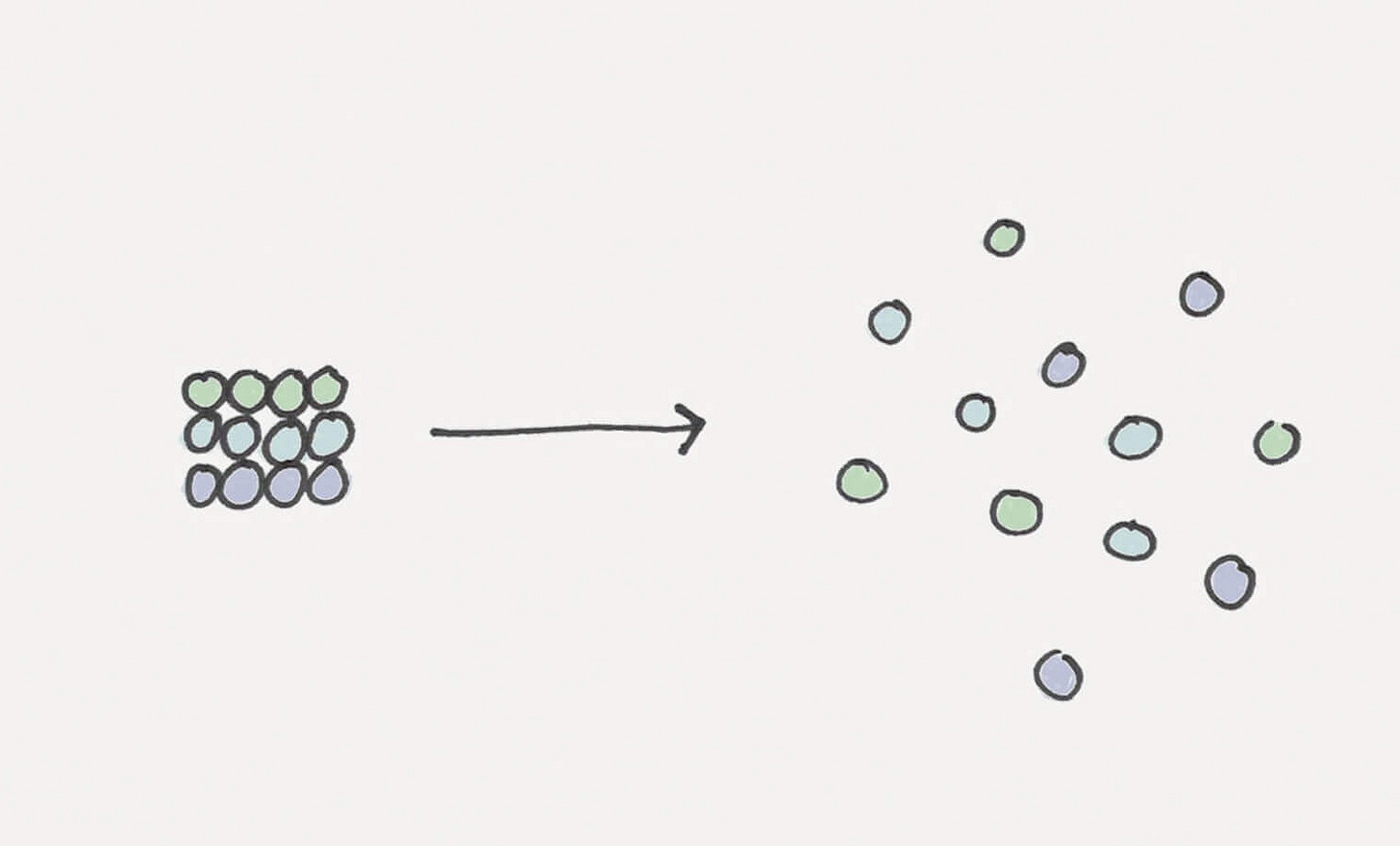

From a tiny bit of concentrated energy, the effect compounds exponentially. In Armenia, the quantum-like diffusion of dissatisfaction online—originally from just about a dozen or so people—was able to snowball into hundreds of thousands of individuals, eventually succeeding in replacing the government in 2018.

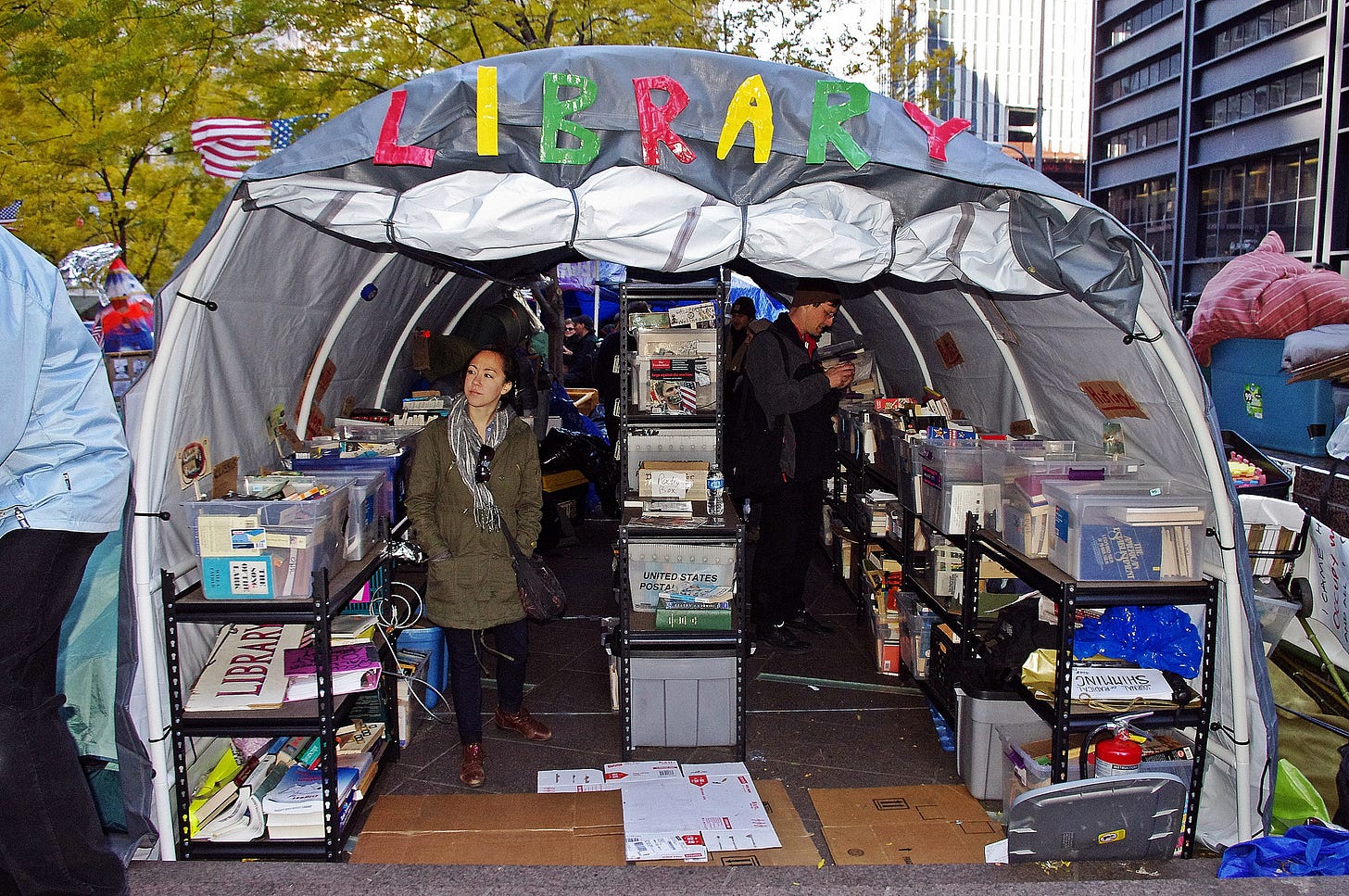

In 2011, Occupy Wall St. activists likened this process to a “swarm.” Conversations over how much of a swarm Occupy really was aside, it has become more real in the years since. Quantum-like politics is about sudden swarms, made possible by the infosphere.

But these swarms so often disappear as quickly as they appear. Examples include the 2011 Spanish Indignados Movement, the 2018-2019 French yellow vests, the 2022 Canadian truckers protest and many others. This is something unique to our time. They are not inherently inclined toward any particular political orientation, either. Sometimes, these swarms do not even produce an electoral outcome, and instead just elicit a stern talking-down from our old institutions.

The most demonstrable effect of all this has been the change in society’s orientation toward the institutions of old: trust toward them has declined to near record lows across all the world’s democracies. Old centers of power are losing their propensity to manage and persuasively explain the world as the public itself becomes more “quantum-like.”

Something New?—Or Same As It Ever Was?

As an explanation, characterizing the present moment as a slide toward a categorically different kind of uncertainty and disorder is compelling. Today’s multi-directional, increasingly complex, and transnational sphere of social relations is still relatively new. We are therefore living through an interregnum period of sorts, with its symptoms still poorly understood.

Altogether, we can say Sarkissian’s diagnosis is correct, but his surprise at its novelty is misplaced. For example, he told CFI Magazine in 2019:

Just as the classic post-Newtonian world was predictable, so was politics, until quite recently. Contrast this to what we know about the quantum world – which is uncertain, yet interconnected, and changes depending on the vantage point of the observer.

This quote should make us pause, because it is a very loaded statement. It is, however, rooted in a certain bias that is quite common.

For the past few decades, there have been many references to the ‘end of history.’ It’s a debate that has been rehashed many times over. With the Western triumph over communism, some had assumed the grand, ideological battles of old were long gone. Western states began to operate with this assumption in mind: it was now time to manage the spoils and simply perfect the system that was viewed as the best of all possible worlds. In short, things would be more predictable moving forward.

Perhaps this helps to contextualize Sarkissian’s bewilderment at the present’s uncertainty. He was a prisoner of the moment, and believed the post-Cold War stasis would go on indefinitely. Such periods of stasis, however, have historically been the exception. Safe to say, they never last. The past century provides us with some obvious examples.

Before World War One, Europe was living through the longest relative peace it had ever seen. For those who frequented the Viennese cafes in May 1914, they had no inclination that their lives would be irreparably changed just a month later. According to Austrian writer Hermann Broch, society had ‘sleepwalked’ into the war in a daze, unknowing what they were walking into. The relative predicability, stability and growth which later followed the Second World War was only possible precisely because unpredictability had so violently broken open the entire world order not once, but twice.

Those living at the beginning of the 20th century saw this potentiality present in their own time. Modernism embodied the period’s acknowledgment of changing perspectives and its volatility. Emergent mass society and its chaotic nature was said to be linked to modernity’s uprooted, shifting perspectives. “From different positions two people see the same surroundings. However, they do not see the same thing,” wrote Ortega y Gasset.3 He would go on to write The Revolt of the Masses, a conservative assessment of the destabilization that the mass could bring to politics.

All this aside, the early 20th century mass was not like today’s swarm. The galvanized peoples then turned to party politics, and elevated it to levels never seen before, be it social democracy or fascism or communism. Today’s swarm, on the other hand, does not function as efficiently on the electoral level nor does it produce clear parties.

Today’s unpredictability is thus of a different variety. Its restless, quantum-like nature has arguably not yet settled into its future. Ironically enough, however, it decided Sarkissian’s future as President: he resigned in January 2022, claiming his office did not have the “sufficient power to influence events.” He was effectively a victim of his own observations.

History has always been something of an open-ended, social laboratory. Since time immemorial, the tendency toward disorder was often viewed as a feared enemy but also a necessary harbinger of the future.

Old Fears of Disorder

Although I began this post using quantum mechanics as a metaphor, there already exists an older term for a physical system’s tendency toward unpredictability. This term is, again, taken from physics: entropy, from the second law of thermodynamics.

There are a few key traits worth mentioning about entropy that have some possible parallels to the social sphere:

It is one of the few quantities in the physical sciences with which you can measure the passage of time.

It is produced by irreversible processes.

Entropy is associated with wasted energy that cannot be used.

In informational theory, entropy is understood to mean a measure of “surprise” or “uncertainty” inherent in a variable’s possible outcome.

I stand by the quantum metaphor as being especially appropriate for our current, digital infosphere. Yet, before the nested, unstable networks of the “world of the very small” made possible by the internet took hold, history did possess an older and more recognizable form of disorder. It was talked about by various writers since Antiquity, often as something to be avoided.

The majority of societies before Western modernity privileged not innovation and flux, but a hierarchy that was relatively unmoving and rooted in a strong sense of social memory. One such example is the Great Chain of Being (scala naturae) concept, which placed all matter and life into a clear order. Even internally, doctors of antiquity viewed illness as a function of disorder: the four fluids believed to make up the body had to be proportional or else there would be depression, liver disease or some other ailment.

In short, entropic disorder is what you wanted to avoid—both in social systems and in biological systems.

For the ancient historian Polybius, unified Roman imperium was a possible antidote to entropy. He called this symplokē or the “the weaving together of all regions of the world and their individual local histories” into a new body.4 The previous world, like that of autonomous Greek city-states, was like “severed limbs and, hence, undesirable.”5 Symplokē allowed for a complete World that was comprehensible, desirable and beautiful for Polybius. Yet, he used drama and suspense to repeatedly illustrate the openness of history, that it really could have turned out entirely different.

Over a millennia later, the Byzantine Greek statesmen Theodore Metochites (1270-1332) wrote openly of how the “the winds shift[ed] from one direction to the opposite” in his own life. Speaking to the instability of Byzantine Roman power, Metochites related this concept of entropy to life itself in his A Lament on Human Life.

And we see the man who yesterday was standing firm, indeed, who was for a long time undefeated by any kind of bodily misfortune, now lying on his back and suffering some malaise in his body, that had, until now, been extremely vigorous, or having lost all his health and now experiencing numerous difficult changes, living with all kinds of sickness—he who for many years seemed completely impervious to the vicissitudes of the body.

Metochites characterized life as fundamentally existing on a flip of a coin, or “turn of the ostrakon” in Ancient Greek. Sudden change can create sudden poverty, seemingly out of nowhere.

Altogether, it is unsurprising that virtually every culture has had some response to the problem of change and improbable chance. Documenting the many discourses surrounding entropy, unpredictability and disorder would be a worthwhile task in itself. The easiest one that comes to mind is one of Buddha’s famous sayings, “change is never painful, only resistance to change is pain.” But what if there was a place safe from the pull and pain of a destabilizing future?

The Past as a Refuge of Stability

In 1806, the Greek-Italian poet Ugo Foscolo looked upon the graves in Venice and Verona with dismay. Two years before, Napoleon’s edict of Saint-Cloud had ordered that all graves were to be buried outside the city and had to be of the same size. Foscolo was incensed. In the poem Dei Sepolcri, he penned his frustration. He wrote of the dead being risen from their tombs to fight the battles of the future. The past, he said in so many words, was the only sublime refuge from the uncertain times ahead. Without it, we are drifting into the void.

Foscolo was a pre-Romantic poet, but he captured the coming sentiment. Perhaps the past could be used as a compelling story, as a possible light-post to guide us instead of fumbling in the dark. Foscolo’s time was a period of rising Neoclassicism, and he took many influences from Antiquity’s reverence for the past. Historical narratives, however, were still so fractured. There needed to be a consolidation of story-telling about the past if it was to ever to be a viable refuge.

The 19th century professionalization of history into national categories provided a potential way out. In a time when many of the fundamental social and economic changes we would today recognize were materializing, academic historians sought to create an objective past. A stable rallying point, perhaps, to ground ourselves as we rushed headfirst into the unknown future. The national histories that emerged during this period and beyond can be viewed as an attempt to harness entropic forces.

Emerging in Germany from the likes of Leopold von Ranke and others, this method of history-writing soon found itself reproduced in Poland, France, the Balkans, and beyond. In Ranke’s own words, the goal was to judge the past objectively ‘how it really was’ (wie es eigentlich gewesen). Ranke himself might not have been so cavalier in asserting history’s stability, but other national writers took this methodology and made it their own. History consequently became the most contested ground.

It was an attractive prospect, to try to harness history into stable categories. Yet, it was also a product of its time. The printing press, standardization of national languages, increasing literacy rates, and other factors allowed for nations to emerge as organic entities beating to the same drum. National history-writing developed as an explainer for this new collective identity. The past was made stable by professional historians, but it was historical forces themselves that ultimately moved peoples into national bodies. The newly produced nation-states now had powers that needed to be persuasively historicized, to both justify their existence and their future actions.

I am not going to recount the suffering that followed this period’s romantic aspirations—the carving up of people and territory, pursuits of glory, wars of territorial expansion, and utopian dreams said to be a continuation of history’s wishes. Much has already been written on these questions. Instead, I recount this to illustrate the central thrust of the long 19th century, which persisted well into the 20th century. In a time of unprecedented change in all spheres of life, history became such a powerful refuge that it was the existential battleground.

A Refuge No Longer

Yet, something seems wrong with this picture. If entropic change then elevated history to unprecedented heights, then maybe the same should be happening today. After all, we are living in an equally transformative time. Why is history no longer a refuge like it once was?

Entropy may be disorder, but it is nonetheless understood as aggregates in classical mechanics. Simply put, it is the world of the very large. In transhistorical terms, we can say entropic disorder corresponds to the world of states and power. In this schema, countering entropic change means creating a balance upset by emergent and competing centers of power.

This was the original problem of states in a shared World which Polybius’s symplokē tried to solve, or competing Great Powers in Europe tried to balance but failed. In modernity, these disorders of global power opened a window for ideological battles and grand historical narratives which reached their zenith during the two World Wars. History was a refuge precisely because it was viewed as explanatory of this disorder, and could even steer it by grounding it in something firm. History possessed power because it directly informed the actions of states and their ideological justifications in this great power contest.

Of course, we still live in an entropic world with disorders of power. To put it differently, we still live in a world of geopolitics. The difference today, however, is that this realm is also being augmented from below, by the ‘world of the very small.’ The emergence of this quantum-like realm forms an entirely new terrain, which exists both inside and outside traditional geopolitical concerns.

Whereas history was a refuge for entropic disorder among states, the quantum-like public is less compelled by it. It is largely a negational force, evidenced by the simple fact that trust in states has declined globally. The past has also become more scrutinized. Once you peel back the criticism of one social facet, rarely does it ever really stop. History thus loses its existential allure as its nested and networked communities produce fractured narratives. The world of the very small is fundamentally an individualist enterprise, although it still possesses some weakened regional and national bonds, depending on context.

Though, I don’t speak of this with any certainty. The pendulum can swing wildly toward grand historicity again, if the multipolar world succeeds in unraveling into blocs or manages to suppress this quantum-like public entirely.

Living in Interregnum

Vladislav Surkov, often called Vladimir’s Putin right-hand ideologist, published his last essay in November 2021 on the problem of entropy. “The state,” he wrote, “is primarily an instrument for reducing social entropy.” Closed systems tend to compound entropy. The solution is thus clear for Sarkov: “Russia will expand not because it is good, and not because it is bad, but because it is physics.”

Aleksander Dugin told reporters something similar. “It is nothing personal”—the war with Ukraine was inevitable, as simply “a law” of geopolitics.

Sarkov’s essay is timely. Last month, I wrote a piece titled The 19th Century Returns where I argued Russia was operating in an old frame that was crashing into our 21st century sensibilities.

Though, when viewed through this entropic and quantum schema, I believe there is another reason to argue this is the case. Indeed, Russia’s actions align with a power obsessed with 19th century geopolitical laws and the strategies employed then to contain entropic change. And it is colliding head-first into the 21st century paradigm of quantum-like social pressures from below. Maybe this explains why Russia lost the information war the second the invasion started.

Surkov, however, views the quantum-like infosphere as an invention of the United States for its own purposes. It never intended to win that battle outright. “The Pentagon is the customer and developer of the Internet,” he writes.

Still, what Surkov fails to grasp is that in the United States too, these quantum-like forces have been chipping away at American narratives of power and trust in them. Regardless of who spurred this development, it has now been put out into the world. One cannot assume that where it originated will be its master, any more than one could have assumed that the British Empire would forever be at the helm of industrial capitalism despite it starting there.

We are now living in an interregnum and the quantum-like forces of uncertainty have not yet reached their highpoint. Antonio Gramsci famously wrote that during such periods of transition, “a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”6 Entropic forces during the long 19th century met their violent ends, and afterwards found their eventual stasis in the post-war settlements. For the past decade, I believe we have been exiting this stasis into uncharted territory. Ultimately, the political state must make space for this emergent quantum-like social sphere or else it will continue to wrestle with it until something breaks.

We can be sure, though, that further bewilderment still lies ahead as history bends more and more toward chaos, at least for now.

Berlin, Isaiah. The Proper Study of Mankind (Vintage Digital, 2012), 450.

Ibid., 449.

An Introduction to the Politics and Philosophy of José Ortega Y Gasset (Cambridge University Press, 2009), 144.

https://arts.st-andrews.ac.uk/latehellenistic/5-politics-aesthetics-and-historical-explanation-in-polybius-i/index.html

Ibid.

Gramsci, Antontio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks, (International Publishers, 1971), pp. 275-276.

Observing the geopolitical chaos of the last month, I’ve felt uneasy in that I’ve been unable to shape my thoughts into anything coherent. This essay helped me find the thread. Thank you.

As a practical chemist, but one that spent at least a couple of courses in the study of quantum mechanics.... I find "the observer effect" compelling. Simply, the act of observation, and/or measurement of a system changes or disturbs that system.