First Contact with America

On three individuals who had wildly different impressions of the United States with world-changing consequences

It’s become less and less common to experience real and genuine differences these days. Some 50 years ago, an average person might have traveled just a short distance from the Soviet bloc to the West and been completely shocked. But nowadays, globalization means there is less and less left to truly surprise. Yet it’s exactly in those surprises that new ideas circulate, history really starts moving in unexpected ways, and people are permanently transformed.

I’ve been thinking about this in relation to the United States. Because not so long ago, this country held a different place in people’s imagination. Part of it was fantasy over opportunities and wealth, but there was also fear over what one would find.

What follows are profiles of three individuals whose first contact with America shocked them to the absolute extreme. The first was disgusted, the second saw the possible seeds of ruin, and the third was enamored by America’s abundance. Each would return to their home countries with historic repercussions for the whole world.

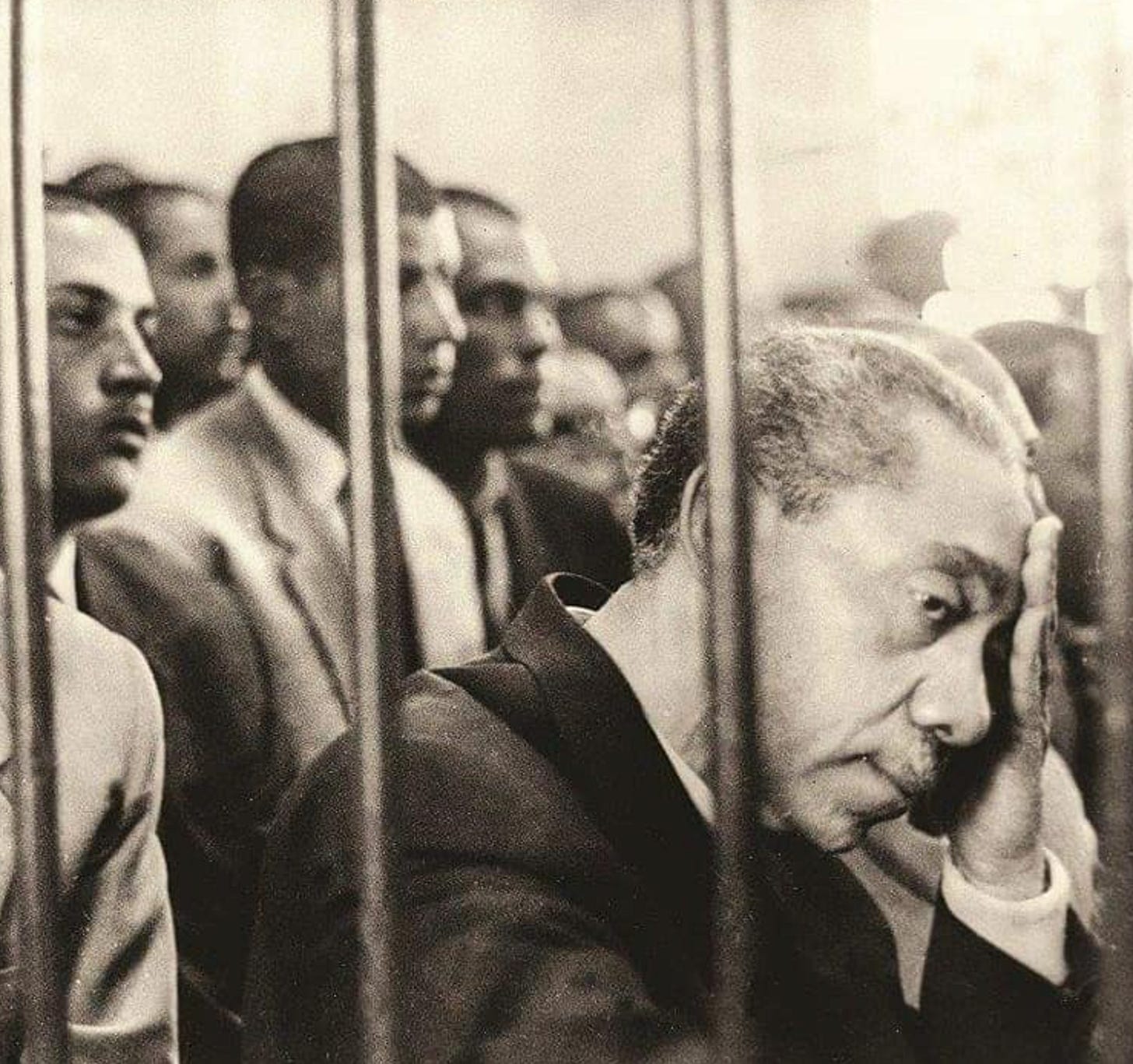

Sayyid Qutb’s America

Sayyid Qutb stayed almost two short years in America from 1948 to 1950. But his experiences provoked such visceral disgust in him that he would return to Egypt completely radicalized.

Qutb is known today for being a leading figure in Islamist thought. After his return from America, he joined the Muslim Brotherhood and became its most famous writer and propagandist. His influence would later be foundational for Islamic fundamentalist groups like Al-Qaeda. He wrote about his experiences in the United States in an essay titled The America I Have Seen (1951).

Qutb’s observations largely center around his time in Greeley, Colorado. By today’s standards, this was a quaint conservative town where even alcohol was illegal.1 Little did this matter for Qutb, however, who saw loose immorality and ugly materialism everywhere.

He viewed Americans as living isolated lives, pruning their green lawns in front of their spiritually empty suburban homes.2 He writes:

During this long period of time and throughout this vast area of space I did not glimpse except in rare occasions a human face which expresses the meaning of man, or a human look from which the meanings of humanity are revealed… but I found the herd everywhere, the raging and wandering herd which knows no direction except pleasure and money.3

One word that often comes up in Qutb’s opinion of America is its “primitiveness.” And practically nothing is spared from this extreme judgment.

His list of damnable things about America is long and often reads like a parody. The United States is said to be regressive in its artistic taste, especially its love of jazz, which satisfies “primitive desires” with claps that could “deafen ears.”4 American films are “simplistic” and, again, “full of primitive emotions.”5 Athletics are full of deranged spectators who value only strength and have no regard for principles, values, and manners of personal life.6 American fashion is said to be made up of “screaming, loud colors and elaborate, large patterns.”7 Not even haircuts are spared — for there was not one instance where Qutb did not return home to “fix what the barber had ruined with his awful taste.”8

Qutb felt America was impressive in its productivity, but lacked any depth. One thread that follows practically all of his observations is his disgust at the relations between men and women. By all accounts, Qutb himself was a man tortured by his sexuality. He was a lifelong bachelor, pale with respiratory issues since birth, introverted, and socially alienated.9 He dedicates long paragraphs to criticizing the sexual decadence around him with its flirtatious girls—described in uncomfortable detail—and the American “dream boys” who pair up with them.

Yet, it was at church where Qutb saw what was, to him, the most lascivious display. Outraged, he wrote: “in America, the church is for everything but worship.”10 He recounts one night in Greeley at a dance which haunted him.

The passage is titled, “A Hot Night at the Church”:

The dance floor was lit with red and yellow blue lights, and with a few white lamps. And they danced to the tunes of the gramophone, and the dance floor was replete with tapping feet, enticing legs, arms wrapped around waists, lips pressed to lips, and chests pressed to chests. The atmosphere was full of desire.

Then the minister descended from his office, he looked intently around the place and at the people, and encouraged those men and women still sitting who had not yet participated in this circus to rise and take part.

[He then] chose a famous American song called “But Baby, It’s Cold Outside.”

And the minister waited until he saw people stepping to the rhythm of this moving song, and he seemed satisfied and contented. He left the dance floor for his home, leaving the men and women to enjoy this night in all its pleasure and innocence!11

It could be said that Qutb was radicalized the moment the needle dropped for “But Baby, It’s Cold Outside.”

Qutb’s experience in America solidified his belief that there are only two kinds of societies: the moral Islamic civilization and the jahili (the “uncivilized”). As he writes in The America I Have Seen, this country had mastered productivity but “no ability remains to advance in the field of human values.”12

He openly asks the reader what is the end-point of this supposedly depraved country:

This great America: What is its worth in the scale of human values? And what does it add to the moral account of humanity? And, by the journey’s end, what will its contribution be?

I fear that a balance may not exist between America’s material greatness and the quality of its people. And I fear that the wheel of life will have turned and the book of time will have closed and America will have added nothing, or next to nothing, to the account of morals that distinguishes man from object, and indeed, mankind from animals.13

Qutb’s observations are clearly steeped in personal projection, deep resentment, and perhaps even self-hatred. But regardless, he believed them wholeheartedly. He returned to Egypt a changed man who proselytized his newfound belief in Islamic superiority and violent jihad. In 1966, he was convicted of plotting to assassinate the Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and later executed.

To Islamic fundamentalists and their apologists today, he remains widely read as a famous martyr who died fighting jahiliyyah or secular Western modernity.

Wang Huning’s America

The last National Congress for the Chinese Communist Party in 2022 was full of intrigue and drama over what would happen. In the end, the expected happened. President Xi was granted an unprecedented third term.

But in the background was another figure reappointed to the elite seven-person central party leadership. Wang Huning, a close advisor to the past three Chinese party leaders, was once again chosen for the top position. Huning is credited with being the country’s chief ideologue and theorist. He is the leading mind behind what values China’s 1.4 billion people should follow, all passed down from the dictates of the party.

Huning himself was something of a prodigy. At age 29, he was the youngest associate professor of international politics in China. Although already widely cited by the time he visited America for a short six months in 1988, his experience solidified his belief in China’s unique authoritarian path and the need for single-party rule. He returned to his homeland with the view that all political power runs downstream from shared values, culture, and tradition.14

Huning saw these aspects disintegrating in America. He felt the United States was slowly breaking at the seams, unable to understand itself, but also admired what the country had accomplished in such a short amount of time. China and America are in an “eternal conversation,” both centers of the world that command respect.15 He compiled all his notes and observations in a 349-page book later published as America Against America (1991).

The title of the book is taken from the Chinese term yíhuò [疑惑] meaning “puzzle” or “doubt.”16 America had effectively turned itself into a yíhuò [疑惑] which has made Americans equally puzzled by their own system.

For Huning, America was trapped in a puzzle. It was in a battle against itself: the ideal America versus what it actually was. Through its great progress, it had also sowed the seeds of its own undoing.

American society itself, it has its affirmative and negative forces, and wherever affirmative forces can be found, negative forces can be found. This is the basic meaning of America Against America.17

This puzzle is all over Huning’s writing as he tries to understand what America really is.

The United States is a very developed society in many respects. Anyone who comes to the US will feel a sort of “future shock.”

One type of person will just think about how they can enjoy being in America; another type of person will ponder why there is an America.18

While Huning was shocked by America’s futuristic quality, he was equally shocked by its rampant homelessness. In fact, homelessness is mentioned in America Against America as one of the most pressing problems. He dedicates a whole chapter to it titled “Begger’s Kingdom.”

He recounts many stories with the homeless in his short travels.

December 1988, New York. When I went to a friend’s house and walked to the door of the building where he lived, I saw a man sitting on the steps, eating. He was disheveled and had a pile of tattered luggage next to him. I couldn’t help but be alert and hesitant to go in. It turned out that the person looked up first and turned out to be an old woman. She said, “Don’t hurt me, I’m homeless, I’m just sitting here to eat, I won’t do anything else.” Hearing her words, a great compassion flooded my heart.19

Huning struggles to understand how America could, despite its great wealth, also create the ugliest conditions for life.

On the night Bush was inaugurated as the 41st president, I saw homeless people sleeping in the doorways of the buildings lining Bush Street in San Francisco. Isn’t this America? Is this America? I’m afraid I can’t answer that with a single word.20

Credit has to be given to Huning for being perceptive in diagnosing cultural trends without any exaggeration or hysteria. The book touches on a surprisingly wide variety of themes: the commodification of life, hero worship, elite interest groups, family life, racism, the power of money, the Native American past, and the American work ethic, among others.

One of his observations in particular would be very influential for China’s new path forward: the power of technology. The use of electronic payments like the credit card shocked him, as did the emergence of computers. But he also understood that this technological process would eventually remake the very people it was supposed to serve.

Sometimes it is not the people who master technology, but the technology that masters the people. If you want to overwhelm the Americans, you must do one thing: surpass them in science and technology.21

One can draw a line connecting Huning’s observations in America and China’s focus on engineering and technological dominance since the 1990s. The Chinese state has also used technological systems as a tool for discipline, like the “social credit system,” perhaps inspired by Huning’s writings and experience in America.

Yet, Huning does not just focus on systems and structures. America Against America is one of the earliest texts to discuss the country’s growing loneliness. He calls it “a disease derived from all developed societies.”22 He dedicates an entire section to this question titled “The Lonely Heart.”

Commenting on one story about a friendless but well-off woman with alcoholism, he pithily writes that “she was alone in society, and society was alone in her.”23 Huning understood loneliness as a deeply destabilizing force. It undoes the social contract, and he repeatedly questions whether Americans understand the long-term ramifications of it worsening.

Huning also argues that loneliness is “major burden on the political system.”24 American loneliness is described a byproduct of its decayed and self-interested social institutions, and that “it is difficult to find solutions as long as such social institutions remain intact.” 25 Now, some 28 years later, American loneliness is affecting all areas of life. With diminishing social bonds, politics has increasingly becoming a chaotic place to project exaggerated hatreds, resentment, nostalgia and an intense desire to be saved.26

Much like Qutb, Huning’s shock with America left him with a nagging question: what will become of this country and the greater world?

Today, America’s development, with its economic prosperity, political processes, lifestyle, and international status, has sown a lot of uncertainty in the world. People in developed countries have this fundamental concern: human science and technology and material life have developed up to this stage. Is this [stage] contrary to human nature? Will it cause the depletion of the earth’s resources? Will it ultimately lead to the destruction of mankind?27

Huning would take all his observations back to China with the main takeaway being that to copy America would be his own country’s undoing.

Today, he is chiefly responsible for the theory and strategy behind China’s culture and values, so that the one-party state can stably rule. For Huning, China must have common story it tells itself, so it not fall victim to same yíhuò [疑惑] that he saw eating away at America.

Boris Yeltsin’s America

It’s said that when future Russian President Boris Yeltsin visited an American grocery store in 1989, “the last vestige of Bolshevism collapsed inside him.”28 Although the detour lasted only 20 minutes, he was in such a state of shock that he was speechless on the plane ride back.

The United States was the first country Yeltsin ever visited outside the Soviet Union on his own. He had already been dined by wealthy Americans before, flown on their private jets, and socialized with the wealthy.29 His trip took him all over the country. But this impromptu visit to a grocery store off State Highway 3 in Webster, Texas surprised him at his core.

Yeltsin reportedly told aides after a long pause that, if Soviet citizens saw what he saw, “there would be a revolution.”30 In this store far away from any urban center, some 30,000 items were fully stocked and sold. Not even the Soviet Politburo had as many options available to them. Yeltsin was stunned: “Does this cornucopia exist every day for everyone? Incredible!”31

His own experience as a regional party secretary was him struggling to procure food supplies for Sverdlovsk, Russia. He had previously organized poultry farms. All of it seemed insignificant having seen this small, well-stocked shop. The experience left him “sick with despair” for his own people whose economy was on the verge of collapse.32

Upon returning back to the Soviet Union, he spoke to journalists about his experience. He spoke of the “madness of colors, boxes, packs, sausages, and cheeses.”33 He relayed to his aides that Americans spent just a tenth on food, with more variety, whereas Soviet citizens spent over half. Thereafter, he decided that his mission was to bring this American dream to the Russian people.34

By 1990, hundreds of other Soviet officials like Yeltsin experienced similar shock at American abundance. America thereafter became a standard by which to judge Russian development. It can be said that the grocery store visit was a turning point for Russia itself. In March 1991, Yeltsin met with a delegation of neoliberal economists from Stanford University. “I want you to help me as you helped Reagan,” he told them bluntly.35

Yeltsin himself knew virtually nothing about the neoliberal reforms he agreed to. Still, he found the American dream so persuasive that he supported them “lock, stock, and barrel.”36

Yeltsin’s hope was to speed run their own path to American-like capitalism. He was elected to the Russian Presidency in June, 1991 and quickly implemented “shock therapy” to privatize the country. The result was a new oligarchy, but it was initially rooted in recreating the American abundance Yeltsin himself witnessed.

Yeltsin may have privately lost all faith in Soviet communism in 1989, but he later declared it openly in a speech to the U.S. Congress in 1992—to thirteen standing ovations.

The idol of communism which spread everywhere social strife, animosity and unparalleled brutality which instilled fear in humanity has collapsed. It has collapsed never to rise again. I am here to assure you we shall not let it rise again in our land.37

As the 1990s came to an end, the relationship between the U.S. and Russia degenerated. However, President Bill Clinton and Yeltsin maintained a close bond. Nicknamed “Boris and Bill,” they met more times than all the Soviet leaders met U.S. Presidents combined.

Unlike Qutb and Huning, Yeltsin did not ask what future America had. Rather, he saw Russia’s future in America’s present. But the experiment ended catastrophically as Russia descended into gangster capitalism by the end of the 1990s. Yeltsin also started to be visibly drunk more and more in public outings.

Yeltsin shockingly resigned on New Year’s Eve in 1999 and appointed his successor, Vladimir Putin. In his address, he apologized outright to the people in a surreal moment and admitted the dream had failed.

I want to ask your forgiveness – for the dreams that have not come true, and for the things that seemed easy but turned out to be so excruciatingly difficult. I am asking your forgiveness for failing to justify the hopes of those who believed me when I said that we would leap from the grey, stagnating totalitarian past into a bright, prosperous and civilized future. I believed in that dream, I believed that we would cover the distance in one leap.

We didn’t. I was too naive in some things, and the problems turned out to be bigger than expected in other things. We ploughed ahead through mistakes and failures. Many people were traumatized by that time of upheavals.

I want you to know – I have never said this before, and I want to say it now – that the pain of every one of you was my pain, the pain of my heart.38

Adam Curtis. The Power of Nightmares (2004) [transcript], 2.

Sayyid Qutb ash‐Shaheed, . The America I Have Seen (1951), 17-18.

Qutb. The America I Have Seen (1951), 18.

Qutb. The America I Have Seen (1951), 7.

Qutb. The America I Have Seen (1951), 19.

Qutb. The America I Have Seen (1951), 20.

Adil Hamudah. Sayyid Qutb: min al-qarya ila al-mashnaqa (Cairo, Ruz al-Yusuf: 1987), 60–61.

Qutb. The America I Have Seen (1951), 12.

Qutb. The America I Have Seen (1951), 13.

Qutb. The America I Have Seen (1951), 4.

Qutb. The America I Have Seen (1951), 3.

As N.S. Lyons writes in Palladium:

Wang elaborated on these ideas in a 1988 essay, “The Structure of China’s Changing Political Culture,” which would become one of his most cited works.

In it, he argued that the CCP must urgently consider how society’s “software” (culture, values, attitudes) shapes political destiny as much as its “hardware” (economics, systems, institutions).

Wang Huning. America Against America (1991), 330.

Huning. America Against America (1991), 5.

Huning. America Against America (1991), 87.

Huning. America Against America (1991), 100.

Huning. America Against America (1991), 100.

Huning. America Against America (1991), 101.

I explored the rise of loneliness and anti-sociality in my piece from a while ago, “The Social Recession.”

This quote is commonly attributed to Lev Sukhanov, an aide to Boris Yeltsin.

Vladislav M. Zubok. Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union (2022), 84.

Zubok. Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union (2022), 83-84.

Zubok. Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union (2022), 83-84.

Zubok. Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union (2022), 83-84.

Zubok. Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union (2022), 83-84.

Zubok. Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union (2022), 83-84.

Zubok. Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union (2022), 233.

Zubok. Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union (2022), 233.

I had never heard of Yeltsin's apology. Interesting article.

ok Adam Curtis