Too Many Wannabe Elites: A Story of Russia (and Possibly America)

A historian claims a unique theory called elite overproduction can predict social unrest. In Czarist Russia, it allowed for nihilism. In America, it's still unclear.

When we think of social upheaval and even revolution, the three catalysts that often come to mind are food insecurity, mass unemployment, and war. We can also include high debts and income inequality in the mix, among others. In recent years, another possible factor has entered the conversation: elite overproduction or the problem of too many prospective elites. It is a term popularized by Peter Turchin, a macro-historian and mathematician who specializes in modeling historical trends.

Turchin has garnered both intrigue and notoriety for pursuing what can best be described as Hari Seldon’s dream. In Isaac Asimov’s sci-fi Foundation series, Hari Seldon is the brain behind a field called psychohistory: a methodology that seeks to predict the future through complex, statistical aggregates of the past. Much like Seldon, Turchin’s work argues that history does have predictive patterns that can be measured with an accuracy similar to the natural sciences.1 He does so by utilizing the heaps of data we have at our disposal nowadays, relying on dozens of socio-economic indicators said to weaken social cohesion, thus creating cycles of unrest. Elite overproduction is one such indicator and likely the most unique of the bunch.

Turchin’s scope has always been exceptionally large, analyzing the long durée of history’s processes to pinpoint patterns. He has even developed his own interdisciplinary field called cliodynamics—a branch of historical dynamics, the scientific modeling of history’s movement. For Turchin, history could be a hard science, and historians could serve as clairvoyants who can glimpse into the future. He has seen a surge of interest lately for predicting in 2012 that the 2020s would be a decade of “major upheaval.”

“If we are to learn how to develop a healthy society, we must transform history into an analytical, predictive science.” — Turchin, writing in Nature (2008)

I’ve always been someone who has viewed history as a literary form with scientific characteristics. Reducing history to mathematical inputs and outputs sometimes misses the point entirely (I’ve written something on this before). Still, Turchin’s concept of elite overproduction has much use.

In this piece, I’ll be tackling both the merits of the theory itself and some limitations of Turchin’s scientific history by discussing a period when elite overproduction was at an acute, practically terminal, stage. The period in question is Russia in the latter half of the 19th century. Artists and writers at the time often spoke of a resentful, educated group that was pushing the country in an unknown direction. Ideologically potent, what became of this faction and their followers ultimately turned out to be of immense consequence to world history.

An investigation into how elite overproduction unraveled Russia could also provide us with some perspective on how to assess the process in our own, present time. But more on all that shortly, because it would first be a good idea to properly define the term as Turchin understands it.

What ‘Elite Overproduction’ Means

As someone who has often privileged looking at social history ‘from below,’ it is sometimes helpful to instead consider things from the vantage point of the very top. In democracies, rivalries within power itself often get misleadingly interpreted as possessing some popular character because that is the way we colloquially speak of its governance. However, given that U.S. electoral party politics has become less willing and able to integrate popular demands for decades now, perhaps an explanation ‘from above’ can be more explanatory.2

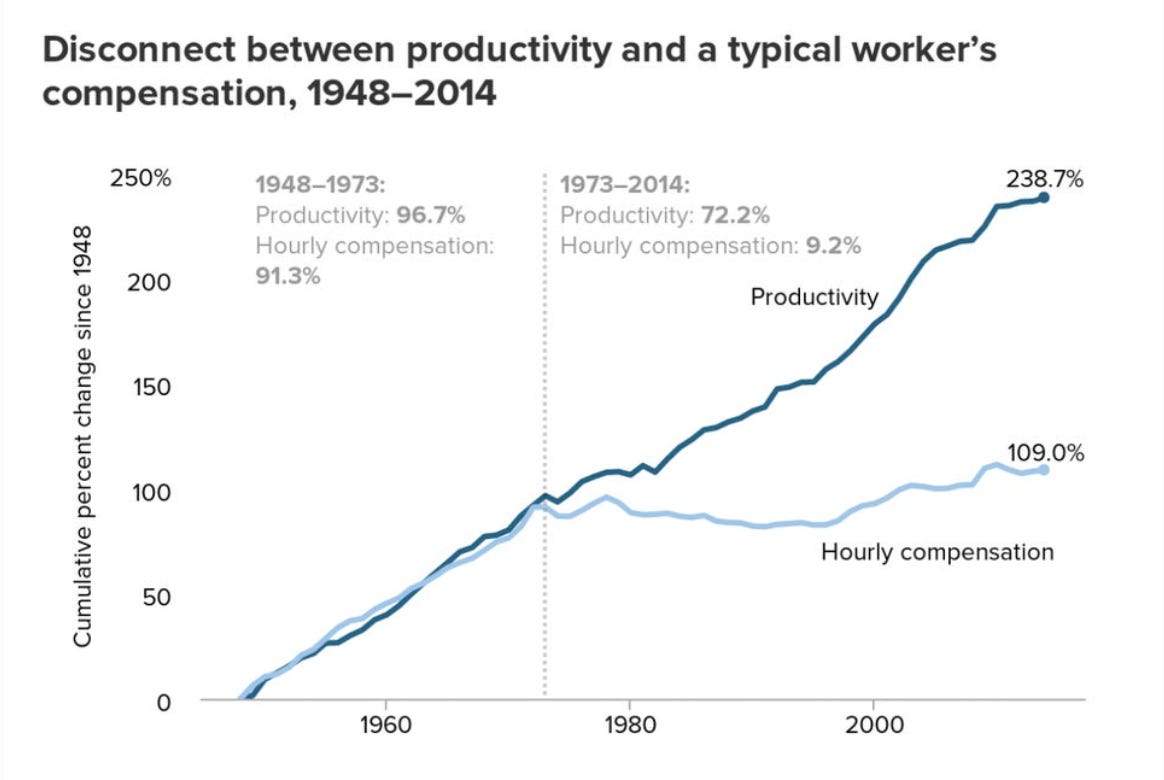

Turchin’s story of elite overproduction in the United States begins in the 1970s when workers’ wages first stopped keeping pace with productivity. You may have seen this chart before.

The resulting income inequality created not only an unprecedented gap, but the sheer number of wealthy people also increased.

According to the research by economist Edward Wolff, from 1983 to 2010 the number of American households worth at least $10 million grew to 350,000 from 66,000.3

As the concentration of wealth-holders increases, so do potential elite members. Turchin defines elites as “power-holders” who are able to influence behaviors by holding top posts within the four areas of social power: “military (coercion), economic, administrative or political, and ideological.”4 There’s some overlap with Turchin’s definition of “elites” and another term, the professional–managerial class (PMC).

Naturally, as the pool of potential elite members grows, so does enrollment within higher education. But because the various centers of social power cannot absorb this larger and larger caste of people, a degree no longer necessarily grants you the status it once did. Many college graduates, even from leading universities, find themselves today chronically underemployed, indebted and despondent. This is essentially elite overproduction: an excess of overly-credentialed people and not enough positions. It causes all areas of social power to become bloated and ill-responsive, effectively working more and more as if solely for-themselves and their own longevity because they must now be hyper-competitive and guarded.

Turchin is not the first to invent this theory, but he has given it a proper name. Some of the earlier assessments of American elite power include C. Wright Mills’s The Power Elite (1956) and others. Yet, it is historian Arnold J. Toynbee’s twelve-volume A Study of History (1934-1961) that most resembles Turchin’s work, at least in spirit. He put forward a cyclical civilizational theory where creative (elite) minorities devolve into dominant (elite) minorities that worship themselves, leading to decay.5 The ruling elites insulate themselves, and become slower and less attuned to the demands of the actually-existing society under them. At the same time, Turchin would argue, more people than ever want to join their ranks. What results is institutional sclerosis and inertia, weakened state capacity, the decoupling of the state from the base of society, and many other symptoms of malaise.

Naturally, there’s many directions you can take this theory. Maybe one could even say its consequences are greatly overstated, but Turchin could not disagree more. He argues elite overproduction is a transhistorical problem not rooted in any particular period. Among his indicators, he considers it “one of the more important factors” in predicting instability across all of history.6

Still, despite its usefulness, there has been little exploration on how this structural problem actually manifests in culture and politics. On account of these shortcomings, I come back to my initial criticism of Turchin’s scientific history for being incomplete. I instead turn to an artist, Fyodor Dostoevsky, for a more compelling understanding of elite overproduction actually rooted in social relations, as he intuitively understood it in his own country in the second half of the 19th century. It was then that a small, educated group was caught between the politically-inert peasantry and the regressive czarist state. Dostoevsky was in literary dialogue with this troublesome segment for most of his life.

Russia’s Educated But Impoverished Nihilists

In April 1866, Czar Alexander II’s life was almost cut short by a rogue assassin in St. Petersburg whose attempt missed. Initially, rumors spread that it was a noble who felt wronged.7 Maybe someone had tried to take the Czar’s life because of his 1861 proclamation freeing the serfs. Others assumed, if not a noble, it must have been some foreign plot. But surprisingly, it was homegrown. “Are you Polish?” the authorities asked the attacker. “No, pure Russian,” he told them.8 The assailant turned out to be a former law student from Moscow University, Dmitry Karakozov, who came from a poor provincial gentry family.9 He had been virtually homeless in the city for about a month before the act, occasionally working a factory job. He suffered from extreme hypochondria and depression. His intention was to kill the Czar to inspire the peasantry and then commit suicide.

Dostoevsky rightfully saw this as one of the most consequential moments in his life. It was the first time a revolutionary had ever tried to assassinate the Czar. Dostoevsky had already gotten a taste for such violence years ago when a group called Young Russia declared, “we will move against the Winter Palace to wipe out all who dwell there.”10 Their leaflets were shoved between door hinges throughout residential St. Petersburg. Karakazov’s attempt on the Czar’s life was this idea finally acted upon. Russia was now surely turning a page, something was in the air, and the unthinkable became possible.

At the time, Dostoevsky was just starting to write Crime and Punishment. The main character, Raskolnikov, was much like Karakazov. He, too, was an impoverished product of the university system and possessed a similar millenarian attitude toward violence. Critics like Dmitry Pisarev openly noted their resemblance.11 But perhaps the greatest similarity between Karakazov and Raskolnikov was their fundamental understanding of why they committed ‘the act.’ Court documents revealed that, after the assassination attempt, the Czar reflexively asked Karakazov, “what do you want?” to which he blankly responded, “nothing.”12 When Sonya plainly asks Raskolnikov for his motive at the end of Crime and Punishment, he responds as if in dialogue with Karakazov’s sentiment, “I just wanted to dare, that’s the whole reason.”13 The act was fundamentally about asserting oneself amid depravity, to dare, to finally be visible. It was about everything and nothing all at once.

Dostoevsky had demonstrated incredible intuition in foreseeing this socio-cultural development, but the coincidences happened not once, but twice. Remarkably, just days before the first chapter of Crime and Punishment was serially published, yet another Raskolnikov-like character appeared in the news. A law student named Danilov had killed his pawnbroker and servant in their apartment.14 The first few chapters of Crime and Punishment were already written by the time it had occurred.15 The crime was so similar to Raskolnikov’s, down to the double-murder, it bordered on prophetic. Later, when the closing chapters of Raskolnikov’s confession were published, they appeared “almost simultaneously with Danilov's trial and his condemnation,” which was widely reported together.16 Early reviews made sure to compare and contrast the psychological state of both young men.

In Danilov and Karakazov and others, Dostoevsky recognized a character profile that would repeatedly be referenced in his novels thereafter. There was a certain, small strata of Russian society that was emanating an energy at odds with the established order. Understanding their ideas and motivations would become Dostoevsky’s main focus for the remainder of his life. In it, he saw the fundamentals of an existential conflict that signaled modernity and one that would soon envelop the entire world.

Who Were the Nihilists?

Although small relative to the total population, this tiny group would grow to become among the most consequential in modern Russian history. They were defined by their rejection of the present state of things. As one memoir wrote, “everything that had existed traditionally and had formerly been accepted without criticism came up for rearrangement.”17 Bazarov in Ivan Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons spoke of nihilists as a group “who doesn’t bow down before authorities, doesn’t accept even one principle on faith.”18

The nihilists were thus negationists, hard rationalists, radicals, and often aligned themselves with socialism and romantic folk-like populism, viewing themselves as if leading a world-historical mission. They made up the ranks of groups like the Land and Liberty (Земля и воля) and People’s Will (Наро́дная во́ля). To wipe away all assumptions, to start new, was the guiding principle. As Bazarov said, “nowadays, the most useful thing of all is rejection—of everything.”19 This rejection was applied not only to thought, but also to traditional styles of dress and demeanor.

But who made up the ranks of the nihilists and their supporters? For a precise answer, let us return to the scientist, Turchin. He has compiled their numbers and background to see whether or not they could really be loosely grouped with elite overproduction.

Turchin’s Assessment

In his 2009 book Secular Cycles, Turchin delineates 19th century Russia as fitting his schema. From 1782 to 1858, the number of nobles increased by over 2.5x and kept growing well into the 20th century.20 Most of them, however, were petty gentry who had few or even no servants. After the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, the landed nobility began to steadily give up their land to merchants and the petty bourgeoisie. Without forced labor, many noble estates that produced grain failed and were sold.

Because the reforms were irreversible, solutions had to be found on how to appease the resentful nobility who had increased in number but were declining in economic terms. The answer was to expand their social and political positions of power. This occurred in two main ways. Firstly, local governing councils called zemstvo were established in 1864 and nobles made up over 3/4th of their positions.21 Secondly, higher education was expanded and the gentry were admitted in unprecedented numbers.

These ‘unprecedented numbers,’ however, were still remarkably small. In 1859, only 8,750 individuals were students of universities or institutes—and by 1897, this number grew to 30,000.22 However, Turchin writes, they still made up the bulk of the revolutionaries in the decades ahead: some “sixty-one percent of the revolutionaries of the 1860s were students or recent graduates,” and an even higher percentage came from the noble strata more generally. 23

Like for Dmitry Karakozov, the prospects for graduates were poor and many were impoverished. Some failed to even finish their studies due to tuition fees or expulsion over political activities. The state and civil society simply could not absorb them, even if the graduates and students wanted it. As Turchin writes:

Whereas the number of [university] students increased fourfold [between 1860 to 1880], the size of the government bureaucracy increased by only 8 percent from 119,000 to 129,000. Even if we add to this number the 52,000 zemstvo positions, it is still evident that only the minority of elite aspirants could be employed.24

The czarist state’s strategy of “education for the few” rather than “modest schooling for the many” had effectively appealed to no one.25 The educated gentry became poorer and resentful, and the peasants remained landless and destitute. A bridge between the two thus became thinkable and even likely. Add yet another element—the emergent industrial working class in the urban centers—and one sees how these three segments converged to end Czardom. Structurally, they all developed less and less of a stake in its continuation. This meant collapse was all but inevitable, finally reaching a head in both 1905 and 1917.

Dostoevsky’s Intuition

Good artists have good intuition and Dostoevsky was no exception. He intimately understood the moment partly because he had once been part of these radical circles.

At 23 years old, Dostoevsky became a sensation for his book Poor Folk (1844), partly thanks to the praise of literary critic Vissarion Belinsky. Through Belinsky, he was exposed to the ideology that would germinate by the end of the century. Belinsky peeled back the layers of Russian society until there was little left to critique. He negated virtually all of it and lectured Dostoevsky about “the end of property and marriage, the end of nations and religions.” Influenced by utopian socialists, he cited Pierre Leroux, Lous Blanc, and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. “There will come a time—I fervently believe it—[…] there will be no rich nor poor, neither kings nor subjects, there will be brethren,” he told the young writer.26

Before being arrested and sent to do hard labor in Siberia, Dostoevsky’s last activity was reading aloud a letter from none other than Belinsky. Belinsky had tragically died the year before from tuberculosis. To the Petrashevsky Circle he frequented, Dostoevsky spoke of the “awakening in the people of a sense of their human dignity lost for so many centuries amid dirt and refuse.”27 The spy in the room later told the authorities the response was electric. Channeling Belinsky, Dostoevsky then directed his ire toward Nikolai Gogol and other reactionary writers, and made an absolute diagnosis of Russia—”look beneath your feet, you are standing on the brink of an abyss!”28

To the growing number of university students and graduates in Russia, the abyss under their feet was becoming impossible to ignore. While authorities may have viewed the nihilists as simply a sect to be squashed, Dostoevsky instead saw them as something homegrown from the soil, augmented by real suffering, and thus had to be understood at the root. These people were genuine, even fervent, in their beliefs. It could therefore not be shooed away through repression because it would inevitably come to a head again (and it did, many times over, eventually succeeding in killing Czar Alexander II in 1881).

Throughout Dostoevsky’s novels, we repeatedly find the trope of the university-educated but disaffected person, let down by the conditions in which they live. Aside from Raskolnikov, we have Ivan Karamazov from Brothers Karamazov, a well-intentioned but pessimistic materialist who eventually succumbs to devilish hallucinations. In Demons, there is Alexey Kirilov, a civil engineer who romanticizes suicide, and Ivan Shatov, a former serf expelled from the university system, along with other minor characters like Arina Virginsky’s sister, a nihilist student. In The Idiot, Ippolit Terentyev is an intellectual nihilist dying of tuberculosis. And in The Adolescent, Arkady Dolgoruky is a young man who eschews his university education, finding it useless, and instead opts to become wealthy ‘like a Rothschild.’ There are, of course, many more examples.

Then, there is the civil service worker—a position that an overqualified, educated person might begrudgingly do despite no fulfillment. The Underground Man in Notes from Underground occupies such a post, lamenting his invisibility in this soulless day-to-day existence. Dostoevsky’s absurdist short story The Crocodile evokes a similar sentiment: a tale of a civil service worker who is swallowed by a crocodile, but continues his work comfortably inside the belly of the beast despite his wife pleading he leave. In the end, she abandons him while contemplating divorce because she cannot afford to buy the crocodile from the animal’s owner.

Finally, there is the noble who has given up all pretensions of morality and social-rootedness. He is a product of the social stratification that is upending all of society, indicative of the ‘abyss under everyone’s feet.’ Nikolay Stavrogin in Demons and Prince Valkovsky in Humiliated and Insulted both fit this anti-social archetype.

Dostoevsky’s characters thus touch on the many socio-cultural dimensions linked to elite overproduction. From the disillusioned students themselves, to the mindless bureaucratic positions they would be working in, to the unrooted and amoral nobles who have lost all regard for the society in which they live—it is all part of an emergent social reality that Dostoevsky linked as unique to his time, a kind of literary historicization.

‘Predicting History,’ But Not Really

For Turchin, social reality is a puzzle dominated by empirical patterns. Accordingly, the highest goal of any study of society is the making of it into a hard science. Predictive accuracy is believed to be further and further developed by studying the confluence of structural forces and its various social indicators.

Perhaps Turchin’s model can help clarify how a certain strata of individuals structurally came to be, but it cannot explain why they adopt the ideas they do. Elite overproduction was certainly responsible for permanently changing Russian society, this much can be measured empirically in aggregates. Yet, ideas and the interpersonal web from which they spawn possesses an uncertainty that goes beyond empiricism. Turchin establishes the broad playing field where historical subjects act, but what emerges from the interplay within it is wide open.

How useful are predictions if their results are subject to such imprecise, wild volatility? Maybe you can loosely foresee coming turmoil, but if you cannot accurately pinpoint how it will manifest, you will likely fail to enact preventive measures to counter it. Your crystal ball, therefore, becomes a lot less useful, more akin to perceiving a vague figure approaching you in the distance that you cannot make out, rather than anything recognizable and able to be acted upon. This is because history is not purely an “analytical, predictive science” like Turchin claims, but inherently interpretive.

What Turchin sees as structural and repeating, Dostoevsky instead viewed as a problem of thought rooted in his time. Dostoevsky viewed reason as fundamentally unable to wholly account for the total sum of society. In a world of uprooted individualism within an educated but resentful stratum, this proved to be the question. As Shigalyov states in Demons, ”starting with unlimited freedom, I conclude with unlimited despotism.”29 In a satire on writer Nikolay Chernyshevsky, Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment argues that the social sphere is merely a problem to be solved like a mathematical equation. Many of Dostoevsky’s characters also confront his question, written during a time when science was gaining recognition as the end-all solution to all social ills—as a possible form of salvation itself.

Yet, as Dostoevsky argues, this view is fundamentally misguided. As he writes in Notes from Underground, when “[man] crosses oceans, sacrifices his life in the search [for two plus two]… he’s somehow afraid. For he senses, once he finds it, there will be nothing to search for.”30 When speaking of social relations, hard empiricism can often conceal as much as it seeks to explain. In Brothers Karamazov, Father Zozima and Ivan touch on this same argument. Theologian Sergei Bulgakov best sums up Zosima’s position as meaning, “for the enlightened eye of the saints, the world is a continuously-enacted miracle [but] conformity to mechanical law of the world […] conceals divine Providence from us.”31 Such a sentiment need not be understood in purely religious terms either. Philosopher Hannah Arendt put it more secularly, “the new always happens against the overwhelming odds of statistical laws and their probability; The new therefore always appears in the guise of a miracle.”32

Perhaps we can interpret Arendt’s words loosely as a critique of Turchin’s scientific history and its claim of hard predictive power. The structural realities of elite overproduction may be visible repeatedly throughout history and across societies. I do not doubt its usefulness as a social indicator. In fact, the idea has succeeded in reorienting my thinking on structural change. Yet, what ultimately sprung from it in Russia was not a pattern, but tantamount to a miracle: the end of the Czar, in what was formerly the most reactionary and traditionalist country in all of Europe, and the establishment of the Soviet Union. By Turchin’s own hand, we can discount his predictive power.

In a later piece I hope to someday write, I will be focusing less on critiquing Turchin’s philosophy of history and instead will be exploring elite overproduction as it has manifested today in the United States. Compared to Czarist Russia, the U.S. has been dealing with this social problem in a far more muted but still unsustainable way.

Edit (September 28, 2022): Historian Peter Tuchin has responded to this piece on Twitter, so I fixed a few minor words for the sake of accuracy.

Peter Turchin wrote on his blog that “there is no discontinuity in precision between the natural and social sciences.“ That being said, he qualifies this by adding that “Specific triggers of political upheavals are difficult, perhaps even impossible to predict with any precision.”

Walter Dean Burnham and Thomas Ferguson, and many others, have done excellent work investigating the relationship between American politics and its diminishing ability to actually incorporate real, popular demand. Ferguson wrote in May 1986, “[this] election gives evidence of further electoral dealignment, with voting defined ever less sharply along partisan lines, and a continued decline in the capacity of conventional politics to organize and integrate electoral demand.” He has done further research on this question in his best-known work Golden Rule: The Investment Theory of Party Competition and the Logic of Money-driven Political Systems. His conclusion is that U.S. political outcomes are more strongly correlated with money than with people which has contributed to the public’s dealignment from both parties.

Ibid.

Sorokin, Pitirim A. “Arnold J. Toynbee’s Philosophy of History.” The Journal of Modern History 12, no. 3 (1940): 374–87.

Birmingham, Kevin. The Sinner and the Saint (2021), 277.

Ibid., 278.

Ibid., 276.

Ibid., 197.

Ibid., 294.

Ibid., 309.

Ibid., 313.

Ibid., .269

Ibid.

Thorstensson, Victoria. “Nihilist fashion in 1860s-1870s Russia: The aesthetic relations of blue spectacles to reality.” Clothing Cultures, Vol. 3, Issue 3 (Sept., 2016).

The Sinner and the Saint (2021), 193.

Ibid., 192.

Turchin, Peter. Secular Cycles (2009), 278.

Ascher, Abraham. The Russian Revolution: A Beginner's Guide (2014), 3.

Kassow, Samuel D. Students, Professors and the State in Tsarist Russia (1989), 16.

Turchin, Peter. Secular Cycles (2009), 281.

Ibid., 278.

James C. McClelland, "Diversification in Russian-Soviet Education," in Konrad Jarausch, ed., The Transformation of Higher Learning, 1860–1930 (1983), pp. 182–183.

Birmingham, Kevin. The Sinner and the Saint (2021), 49.

Ibid., 83.

Ibid., 84.

Dostoevsky, Fyodor. Demons. Trans. Constance Garnet (e-artnow Editions, 2013), 157.

Dostoevsky, Fyodor. Notes from Underground. Trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (Vintage Classics, 2011), 32.

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition (University of Chicago Press, 2018), 178.

Some questions to consider:

1. Can we force the size of the elite to the smaller, if so, how? Curtis Yarvin recommended shrinking the elites from 1-in-5 to 1-in-20, and the solution converges with Patrick T. Brown's "Mid-Tier Underproduction" thesis, i.e. Esty-fication of craft and art.

2. Since elite overproduction may be a symptom of a bigger problem, would it be caused by other things? e.g. Turchin's Big Gods Theory, Samo Burja's Elite Founder Theory

3. Is this pattern recognizable on the smaller scale (organizational and social)? It seems to converge with concepts such as The Venkatesh Rao's Clueless, L. Dean Webb's Counterelite, "Midwit", "Small-Souled Bugmen", and others.