This short essay was inspired by Oleksiy Radynski’s documentary “Infinity According to Florian” which is now screening at the Sculpture Center in Long Island City, Queens, New York every Thursday from January 25 - March 25, 2024.

Siberia’s vast expanse, encompassing some 9% of Earth’s landmass, has long stirred great minds, often under extreme duress. Historically, it has been a place of forced labor, exile, and otherwise unlikely friendships.1 The region is also home to many different indigenous peoples along with other settlers from faraway places. This social environment uniquely shaped its inhabitants, as did the land itself whose frigid terrain both inspired and terrified. But as difficult as everyday life so often was, one could still look up and admire the beautiful northern lights.

For the artist Florian Yuriev (1925-2021), the northern lights left a deep and lasting impression. His childhood was spent exiled in the Far North. His father, a biologist and geneticist, fell out of favor with the Stalinist state and Yuriev’s young life was spent wandering around Gulag villages. “The main thing my childhood memory recorded was gray mountains of ore dumps and gray crowds of half-alive prisoners,” he recollected.2 Such broken conditions only drew him closer to the symphony of colors above, with its magnetic storms and rainbow auroras.3 “Since I was a child, I’ve never seen anything good besides the northern lights,” he has said.4

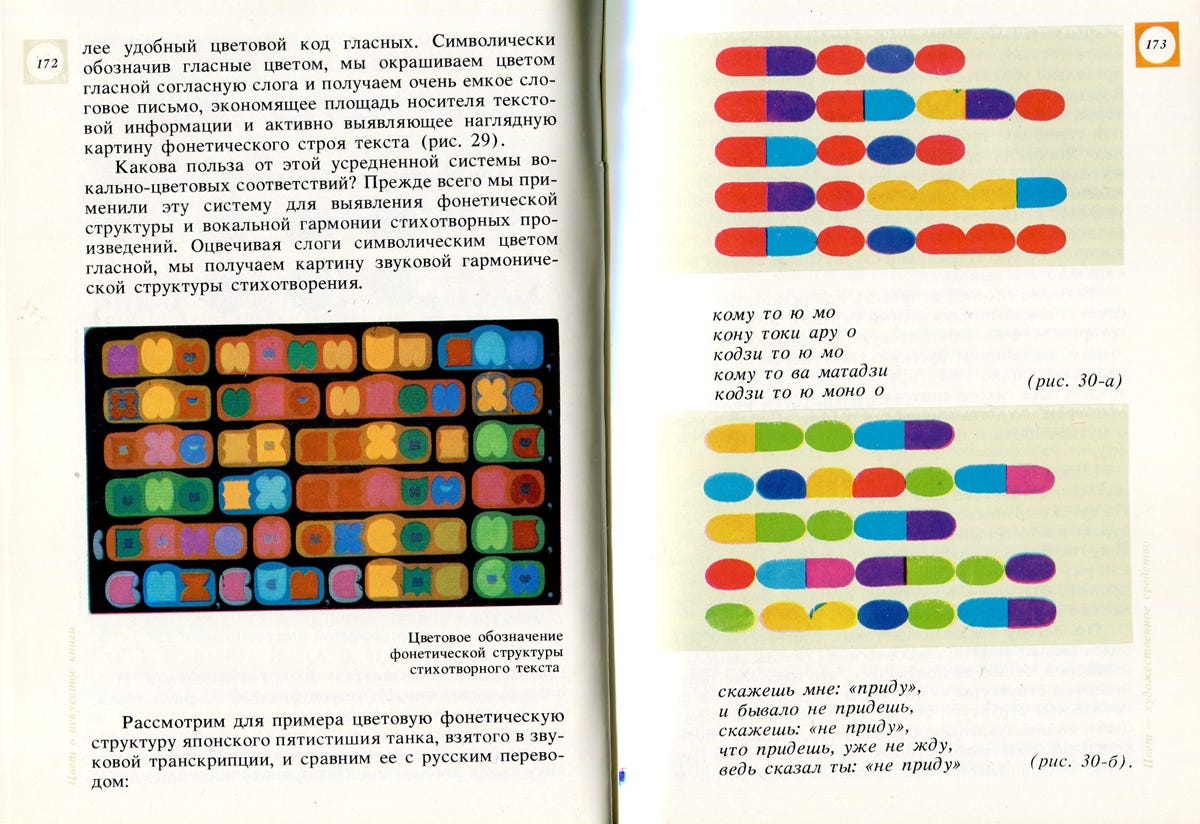

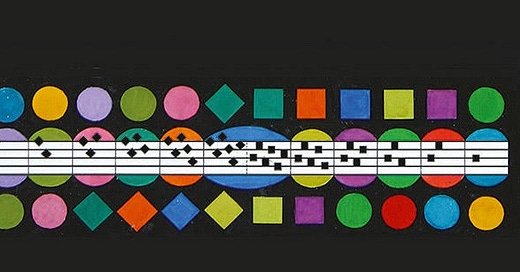

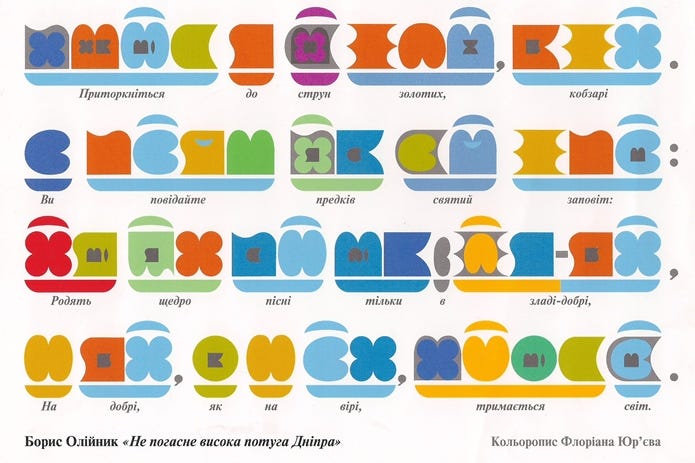

For Yuriev, to say these colors were a “symphony” would be literal. Color was a synesthetic experience for him, and his time in Siberia produced a lifelong fascination with “color-music” or applying color to music (and poetry). It was while living with the many different exiled peoples and languages spoken in the Gulag camps that he decided to create his own language.5

Creating an Artistic Language

While he carried his experiences in Siberia with him, Yuriev did not spend most of his life there. In 1950, he moved to Ukraine to pursue architecture at the Kyiv State Art Institute. It is in this city that he would reside for the remainder of his life, working for “Kyivproekt” as a senior architect until the 1970s, and as a teacher afterward.

Although formally employed as an architect for a long time, Yuriev’s independent creative life focused on art as a synthesis of painting, music, and poetry. As he reflected in a 1987 manuscript, his thinking was a continuation of the 18th and 19th-century Romantics.6 Many of them wrote of “universal connections” between different forms of art. As the poet Novalis asked, “shouldn't the rhyme correspond to the figure, and the sound to the color?"7 “In the works of the greatest poets there often breathes the spirit of a different art,” similarly wrote his contemporary Friedrich Schlegel, “might not this be the case with painters too? Does not Michelangelo paint like a sculptor, Raphael like an architect, Correggio like a musician?"8

Yuriev began actively engaging with such questions from the mid-1950s onward by first applying color painting to poetry. This was also the start of Nikita Khrushchev’s rule over the country which allowed for a thaw in Soviet society. The state’s grip on the cultural sphere somewhat loosened, and new modes of understanding art and society emerged.

Oddly enough, Yuriev was not alone in his interest in color music. Around this time, other forms of synesthetic art were being explored by artists and even scientists in the Soviet Union, especially in the Ukrainian SSR.9 In the city of Kharkiv, the artist Yury Pravdyuk (1924–2002) pioneered compositions of “musical light-paintings.”10 In 1969, he opened the Hall of Color-Music dedicated to the practice which featured live orchestral performances. In Odessa, the artist Oleg Sokolov (1919-1990) formed the Color, Music, Word club dedicated to visualizing poetry and music. It was intended for “people who shared a synesthetic mode of thinking… scientists, engineers, artists, poets.”11 In 1956, Sokolov also hosted one of the first “apartment exhibitions” of the Ukrainian art underground. Beyond the Ukrainian SSR, the city of Kazan saw the establishment of the Prometheus research group, led by physicist Bulat Galeyev (1940-2009), which specialized in visual music.12 The institute, almost entirely made up of scientists, developed “light-instruments” and public spaces responsive to sound, among other experiments.13 In 1983, it organized performances in the Theater of Light and Music in Uzhgorod, Ukrainian SSR.14 But even earlier, at the beginning of the 20th century, color music was famously the fascination of Russian artists like composer Alexander Scriabin, painter Wassily Kandinsky, and many others.15

Yuriev himself arrived at such conclusions intuitively through experience. He believed “all of nature instructs us with color,” and always stressed his work was representative of realism.16 Yet in 1962, he was harshly punished for “abstractionism” when presenting his color-music paintings at a Union of Architects exhibition. The event was abruptly closed, his presented work destroyed, and he was almost expelled from the Union of Architects. That same year, his monograph “Music of Light” was also banned.17 Yuriev could have been sent to a labor camp for over a decade, partly because he had also torn up his Communist youth ID in public and called a Moscow official “scum.”18 His superiors, however, ultimately deemed his “mistake” to only be in painting. Since he was professionally an architect and not a painter, he was spared the worst of punishments.

A Theater for Color-Music

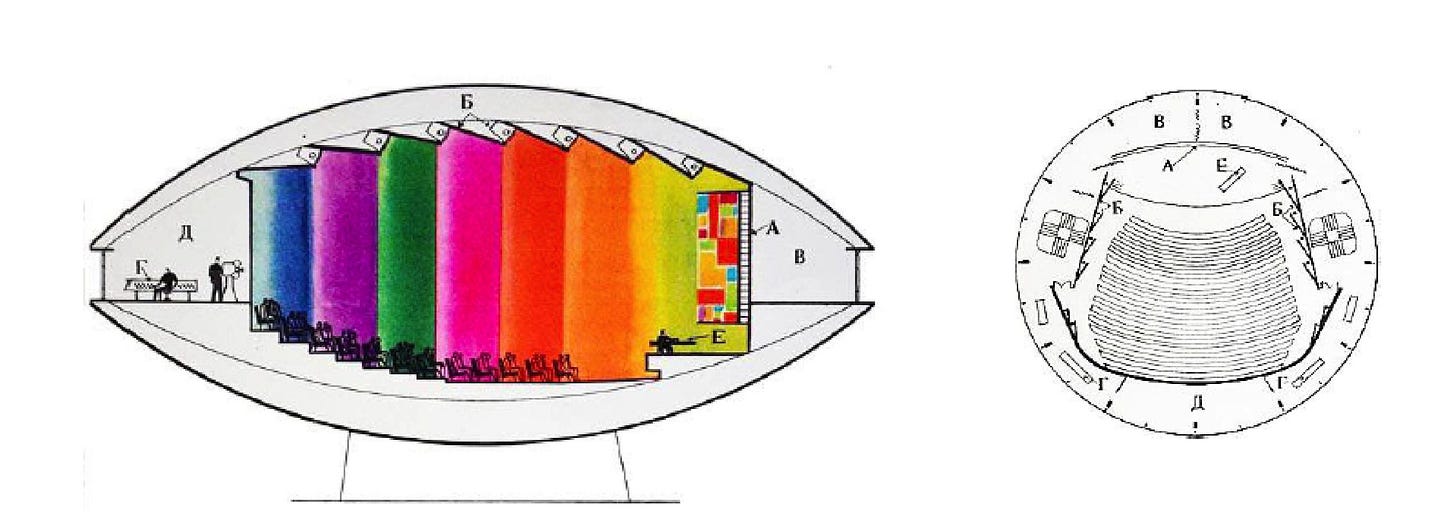

During the 1960s, Yuriev began to apply his architectural expertise to other artistic interests and developed plans for a “light music theater.” Commonly called the “Flying Saucer,” the structure is today a modernist relic of the Ukrainian SSR, but was never actually built as Yuriev intended. Instead, it was revived in the late 1970s by the KGB who took a liking to its futuristic design.19 It was then constructed, but as part of the Institute of Scientific and Technical Information instead. It still stands today.

The last years of Yuriev’s life revolved around the drama surrounding the Flying Saucer. As Oleksiy Radynski’s 2022 film Infinity According to Florian documents, although he was estranged from the old Soviet system, he now found himself equally estranged from the demands of the new capitalist economy. The film follows Yuriev in his public dispute with a real estate tycoon who initially wishes to demolish the Flying Saucer, but then pushes to incorporate it into his new commercial mall.

The conflict demonstrates much of Yuriev’s core personality: his contrarianism, individuality, and deeply holistic view of art. Fundamentally, he was against all ideological impositions on his work: “Back then, the dictate was ideological and now it is economical. It is still ideology all the same.”20 He was not someone interested in ideological justifications. The sum of the world’s parts, it seemed to him, had gone adrift. “Architecture is a reflection of social relations,” he says, “and social relations are in chaos. This is reflected in architecture.”21

Living with Dignity

In listening to Yuriev’s words, one cannot help but hear a melancholic undertone in his view of life. His worldview was molded by the gray world which he was born into. It is for this reason that Yuriev believed he had “never seen anything good besides the northern lights.” Nature was for him instructive but was also being actively destroyed, and he felt it was “no longer able to cope with humans.”22

But his work should not be confused with fatalism or misanthropy. If he was a real fatalist, he would not have been so prolific. Throughout Infinity According to Florian, we see an artist living life with a sense of dignity in the company of others. It is a philosophy rooted in a realistic assessment of the long tail of human affairs, and how to make it all meaningful despite its transience. Infinity According to Florian closes with a monologue that ends on a touching note:

Everything is mortal: Humanity, civilization, the galaxy. Just as every person should behave with dignity before dying, civilization should behave with dignity. Human civilization is like one divided by infinity… in mathematics, this equals zero. This is the entirety of our culture, this is our entire ideology. This is our entire knowledge in comparison with the infinity of the universe and its law. We can formulate anything we can for our own self-affirmation. But the result is zero. Still, this is not a simple zero. From my point of view, this should be a beautiful zero.23

In 2021, Florian Yuriev passed away at the age of 92. He joked that he lived a long life despite his cancer diagnosis because he was a contrarian. Even at his advanced age, he was still occupying his time with exhibitions, lectures, and carving handmade violins out of wood. His life was one where he always felt he needed to further complete something: “I’m not ready to die, I just need to sit down and finish with no distractions…”24 And true to himself, he held onto this otherworldly work ethic his entire life.

The experiences of those exiled in Siberia would produce literature, political ideologies, subcultures, and entire worldviews that would have profound consequences for Europe, Asia, and beyond. For example, it was while in exile that Fyodor Dostoevsky developed the literary acumen that would make him who he was. He also formed life-changing friendships, like with Shoqan Walikhanov who was a Central Asian folklorist and pioneer of Kazakh historiography.

Творчість Флоріана Юр’єва та нові виміри художнього синтезу [The Creativity of Florian Yuryev And the New Dimensions of Artistic Synthesis], pg. 101.

Just this past November, a rare geomagnetic storm lit up the skies of Siberia’s Far East with vibrant colors of green, red, and yellow.

Infinity According to Florian. Directed by Oleksih Radynski. (00:02:14).

Infinity According to Florian. (00:26:38).

Творчість Флоріана Юр’єва та нові виміри художнього синтезу [The Creativity of Florian Yuryev And the New Dimensions of Artistic Synthesis], pg. 105.

The Creativity of Florian Yuryev And the New Dimensions of Artistic Synthesis, 105.

The Creativity of Florian Yuryev And the New Dimensions of Artistic Synthesis, 105.

Sergei Zorin. “Musical Color-Painting: In Memory of Yu. A. Pravdyuk.” (2005), pg. 61.

Elena Shelestova and Igor Oleynik. "Linking Image and Idea: The Artwork of Oleg Sokolov." (1994), pg. 427

Some more info on Prometheus’s odd inventions (with links to some photos).

Quoted from the monoskop wiki:

The group developed various music-light instruments, including Prometheus-1 (1962; used to conduct the first in USSR performance of Scriabin's Prometheus, including lighting part in author's transcription), Prometheus-2 (1963; used in 1963-1964 to perform visuals to the music by A.N.Scriabin, M.P.Musorgsky, N.A.Rimsky-Korsakov, I.F.Stravinsky, F.Z.Yarullin), Crystall (1966; used in 1966-1970 to perform visuals to the compositions Dark Flame by A.N.Scriabin, The Structures by P.Boulez, The Tears by A.Nemtin, The Firework by K.Debussy), and Prometheus-3.

The most remarkable device designed by the group’s researchers was the Man-Machine, which was meant to monitor the activity of various types of electrical systems, from assembly lines in factories to rocket ships. When everything was functioning correctly, the screen would show a luminescent visualization that was set to music. If there was a glitch, the screen changed to a red, pulsating surface set to an unpleasant sound.

Russian composer Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) invented a single “color organ” for his composition Prometheus: The Poem of Fire. Yet, how to interpret the musical arrangement with light and color is notoriously hard to decipher. Yuriev was very interested in this piece, which is how I came across it.

Infinity According to Florian (00:23:30)

Infinity According to Florian (00:36:45)

Infinity According to Florian (00:29:16)

Infinity According to Florian (00:11:50)

Infinity According to Florian (1:00:46)

Infinity According to Florian (1:04:35)

Infinity According to Florian (00:54:21)

What a fascinating person! Thanks for writing this.