The Internet Is Like a City (But Not in the Way You'd Think)

Rereading Christopher Alexander's classic 1965 essay "A City Is Not a Tree" in the digital age

In the days of the early internet, the language to describe it was still an open question. Cultural critic Howard Rheingold, credited with coining the term “virtual community,” likened it to a great frontier. “The pioneers are still out there exploring,” he wrote, with its borders undetermined.1 But even in 1992, Rheingold wrote of this emerging virtual world as being threatened by the physical world outside it: nefarious political interests, private monopolies, and those “putting up toll roads on the information networks.”2

These kinds of concerns were common then. There was a fear that the internet might end up mirroring the stagnation of the physical world and all its problems. Still, the language of the physical world, particularly that of cities and urbanism, could not help but find its way into descriptions of the early internet. It was the most intuitive way of understanding this new place.

During the 1990s, the internet was commonly called the “information superhighway.” Famously popularized by Al Gore, many major conferences and government efforts were pursued bearing the name.3 Others went further — “homes” would be personalized pages, "neighborhoods” would be set up for mutual interests, “community leaders” would be moderators, and sprawling “cities” would be established. In City of Bits (1995), urban designer William J. Mitchell compared every piece of urban life to its virtual counterpart: from galleries to schools to trading floors.4 Yet, nowhere was the analogy more real than in Geocities, a website where users lived in an online metropolis of over 35 million homepages they themselves created.5

Since then, we’ve moved on from describing the internet in dated city metaphors. It grew too large to need an analogy to be understood. In fact, today it is often the other way around. Cities are commonly mapped and surveilled like the internet, said to be made up of “networks” and clusters of “users.”

However, it may be worth revisiting the city analogy for a different reason entirely. I’ve been rereading architect Christopher Alexander’s famous 1965 essay A City Is Not a Tree. In it, he argues that the fundamental problem of city planning lies in the limits of our minds and how we intuitively categorize our surroundings. These biases are unknowingly reproduced by top-down administrators and designers, often with good intentions, but make for bad outcomes. Reading his essay in 2024, I couldn’t help but be reminded of the internet. Nowadays, seemingly everyone seems to admit online life is getting worse, both in quality and how dynamic the web used to be. At the same time, we’ve seen big tech platforms and governments be more proactive about making the internet “safer” and more “truthful.” Yet, the problem practically remains the same, if not worse.

A City Is Not a Tree can provide us with some answers. As Alexander argued almost 60 years ago, our minds are inclined to categorize the world as a tree, but an organic society and city actually resembles a semilattice. And just like with a city, organizing the internet like a tree stifles it completely.

Why a City Is Not a Tree

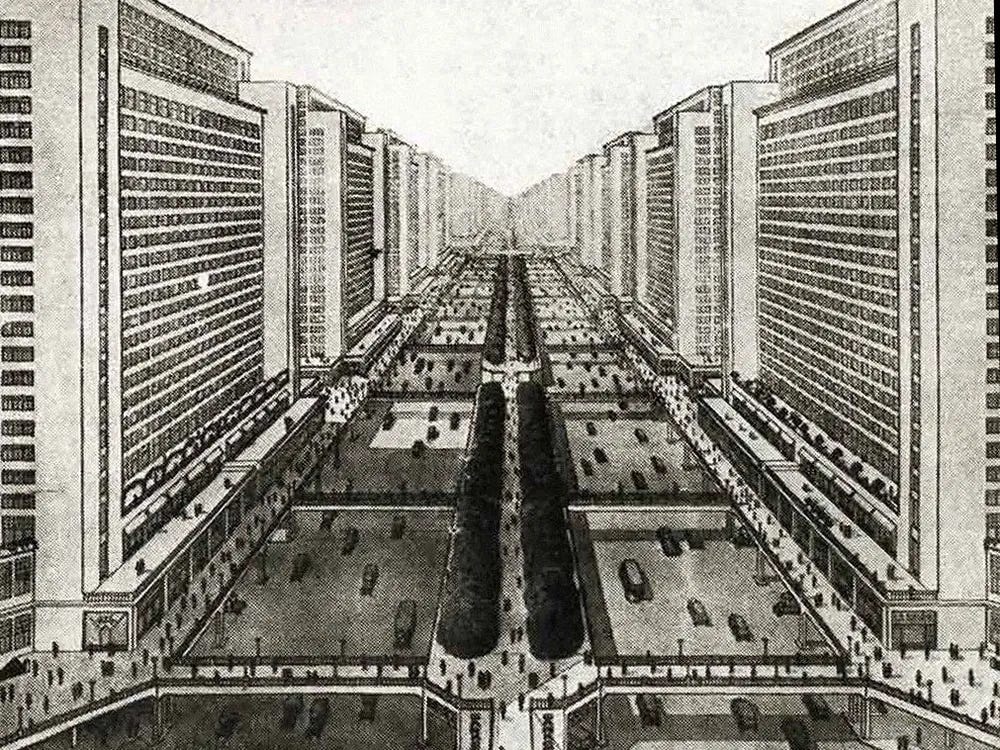

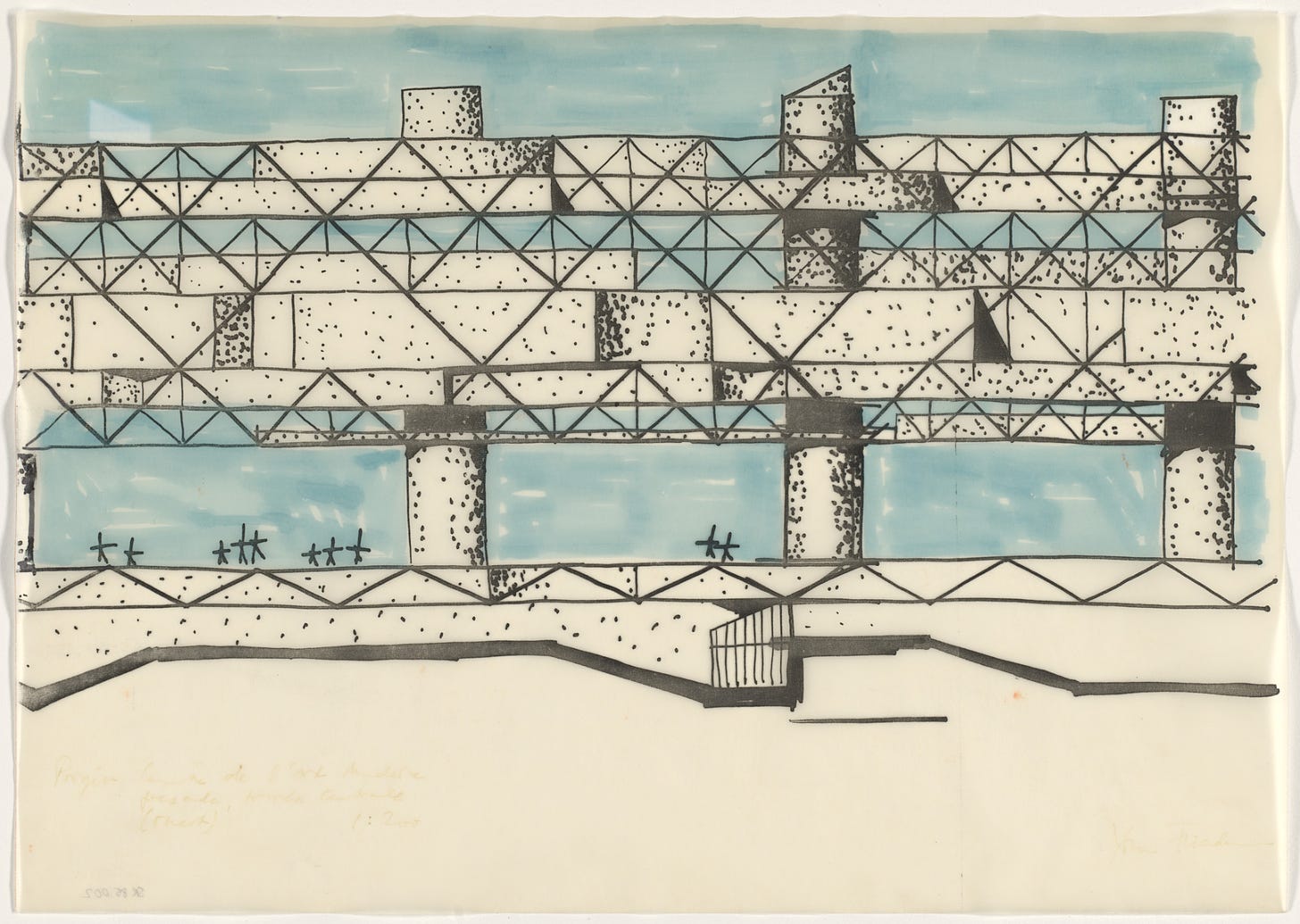

The early 20th century saw the rise of the managerial state, and one of its hallmarks was the planned city. With scientific and technological breakthroughs, some believed every facet of urban life could be measured with precision and redesigned—from automobile traffic to living quarters to shopping. In the two decades after World War II, this confidence in scientific management only grew stronger as part of a trend called “high modernism.”

Yet, when such sentiments were at their peak in 1965, Alexander described results as being entirely unsuccessful. Even modern architects themselves, he argued, preferred to live in older cities built over many, many years rather than their own modernist creations.6 And the general public, “instead of being grateful to architects,” viewed the onset of “modern buildings and modern cities everywhere as an inevitable, rather sad piece of the larger fact that the world is going to the dogs.”7

A City Is Not a Tree would go on to be widely influential, in no small part due to its urgent and conversational tone, but also because of what the essay revealed. Alexander sought to explain the difference between organic cities—like Siena, Manhattan, Liverpool, and Kyoto—and deliberately planned ones like Levittown, Brasilia, and the British New Towns.8 Criticizing his fellow architects for merely mimicking older organic cities, Alexander was instead interested in understanding what truly gives a city life.

According to Alexander, what gives them life is their organizing principle: how the countless different parts come together to make up the complexity that is the city and its society.

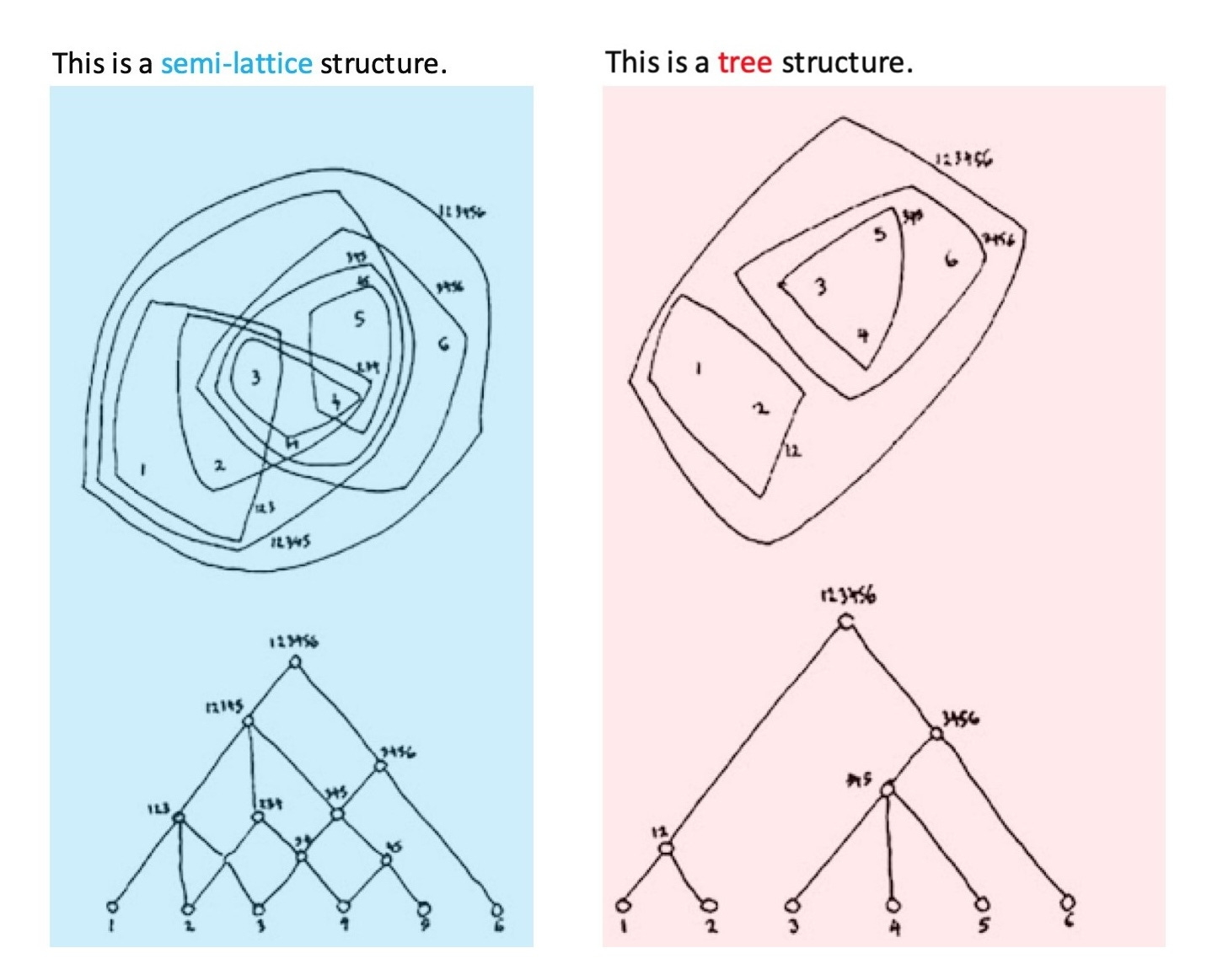

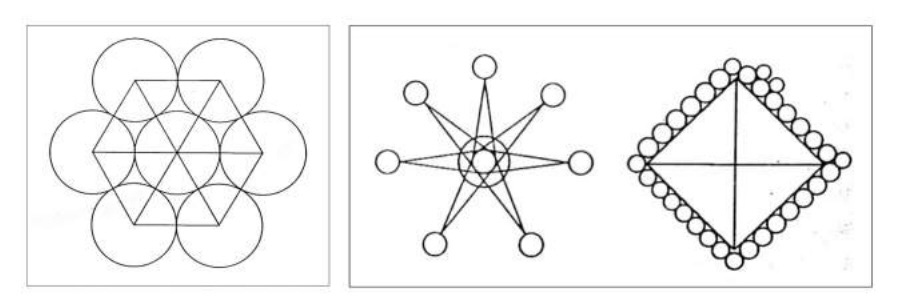

I believe that a natural city has the organization of a semilattice; but that when we organize a city artificially, we organize it as a tree.9

This simple distinction between how a system is ordered determines its entire shape. In fact, it’s not just visible in city planning, but is a basic constituent of how any complex world organizes itself. Such order is also seen in nature, music, and our own social networks.10

In a tree-like system, parts of the whole are conceived as largely separate branches. In a planned city, this might be represented as a section purely for consumption (i.e. malls), a section purely for residences (i.e. suburbia), and another purely for work.11 Highways commonly connect these parts. Tree-like planning could be based on other criteria as well, such as an area intended only for senior citizens apart from the rest of the neighborhood. In still other cases, the branches may be more subtle. But altogether, each tree is rooted in centralized points that branch out into largely separate worlds.

A semilattice, in contrast, possesses much greater and subtler complexity. Practically all its parts are said to overlap, forming a web of relationships. As Alexander writes, “a tree based on 20 elements can contain at most 19 further subsets of the 20, while a semilattice based on the same 20 elements can contain more than 1,000,000 different subsets.”12 When extrapolated to a grand scale, one easily sees how the dynamism of an organic city produces a certain spontaneity and life that cannot be easily comprehended. A semilattice is simply too complex to visualize in our minds.

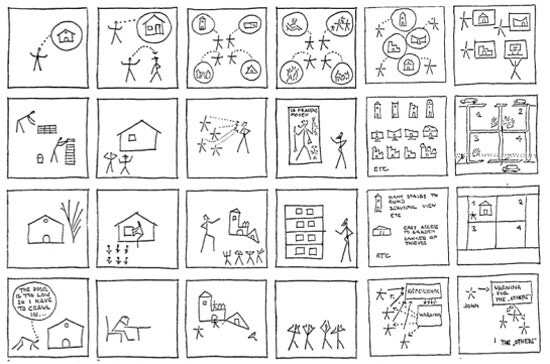

Additionally, as Alexander points out, the actual social structure of our lives resembles a semilattice. Our own personal networks are thick with overlap with friends and acquaintances, many of whom do not know each other. In any modern society, “there are virtually no closed groups.”13 An organic city therefore must mirror the organic social life of the individual. “A living city is and needs to be a semilattice,” writes Alexander, and its dynamism declines when forced into a tree.14 It is this complex web of overlap that allows for the emergence of new ideas, creativity, collaborations, and relationships. They also make it possible for third places to emerge.15 Recent mathematical efforts to prove Alexander’s thesis have validated semilattice-like cities as conducive to life.16 Any conclusions, however, need to be tailored to local specificities. In the essay itself, Alexander critiques nine examples of tree-like “artificial cities” through diagrams.17

Urban planners repeatedly adopt tree-like structures because the mind has an “overwhelming predisposition to see a tree wherever it looks.”18 It cannot “encompass the complexity of a semilattice.”19 Instead, the human mind simplifies complex systems into groupings based on characteristics like type, proximity, and other patterns.20 Experiments conducted by Alexander and A. W. F. Huggins at Harvard University (1964) found participants “almost always invented ways to see patterns as trees.”21 Alexander also quotes the work of psychologist Frederick Bartlett’s Remembering (1932) in demonstrating that, when faced with complexity, the mind naturally simplifies phenomena into tree-like groupings to best remember.

Discussions aside about whether organic cities really are like semilattices (or some other overlapping structure), Alexander’s observations reveal a simple yet fundamental concept.22 Still, tree-like structures shouldn’t be viewed as inherently negative since they sometimes may be necessary.23 And neither is overlap in every instance positive because, as Alexander writes humorously, “a garbage can is also full of overlap.”24 The overlap has to be in the interest of fostering meaningful connections.

A City Is Not a Tree reveals that the underlying order that gives an organic city life is largely invisible to our common perception. Unknowingly and often with good intentions, planners transform the semilattice of organic life into an artificial tree that does not resemble life.

The Internet Is Not a Tree

In the past two years, discussions on how the internet has gotten worse have become so common to the point of being a cliche. That being said, the trend is hard to ignore. In a recent lecture, Cory Doctorow quoted hacker Tom Eastman in diagnosing the current situation online as “five giant websites filled with screenshots of text from the other four.”25 Nowadays, it might be more accurate to replace “text” with “short-form video.”

Doctorow himself is a longtime blogger who has been on the front lines against what he calls the internet’s “enshittification,” a term so popular that last year it was Word of the Year. You may have already heard of it. The word nicely captures the idea that internet platforms are in decline, largely due to investors clawing back value for themselves at the expense of the user experience. No platform is spared this insidious process—Google searches are full of SEO spam; Amazon listings are increasingly suspect and stuffed with keywords; Facebook is no place for socializing; Reddit forced an increase of its API pricing despite protest; and dating apps use dubious methods to keep users paying and looking for as long as possible. And this is just a short list of platforms that have been given the privilege of being “enshittified.”

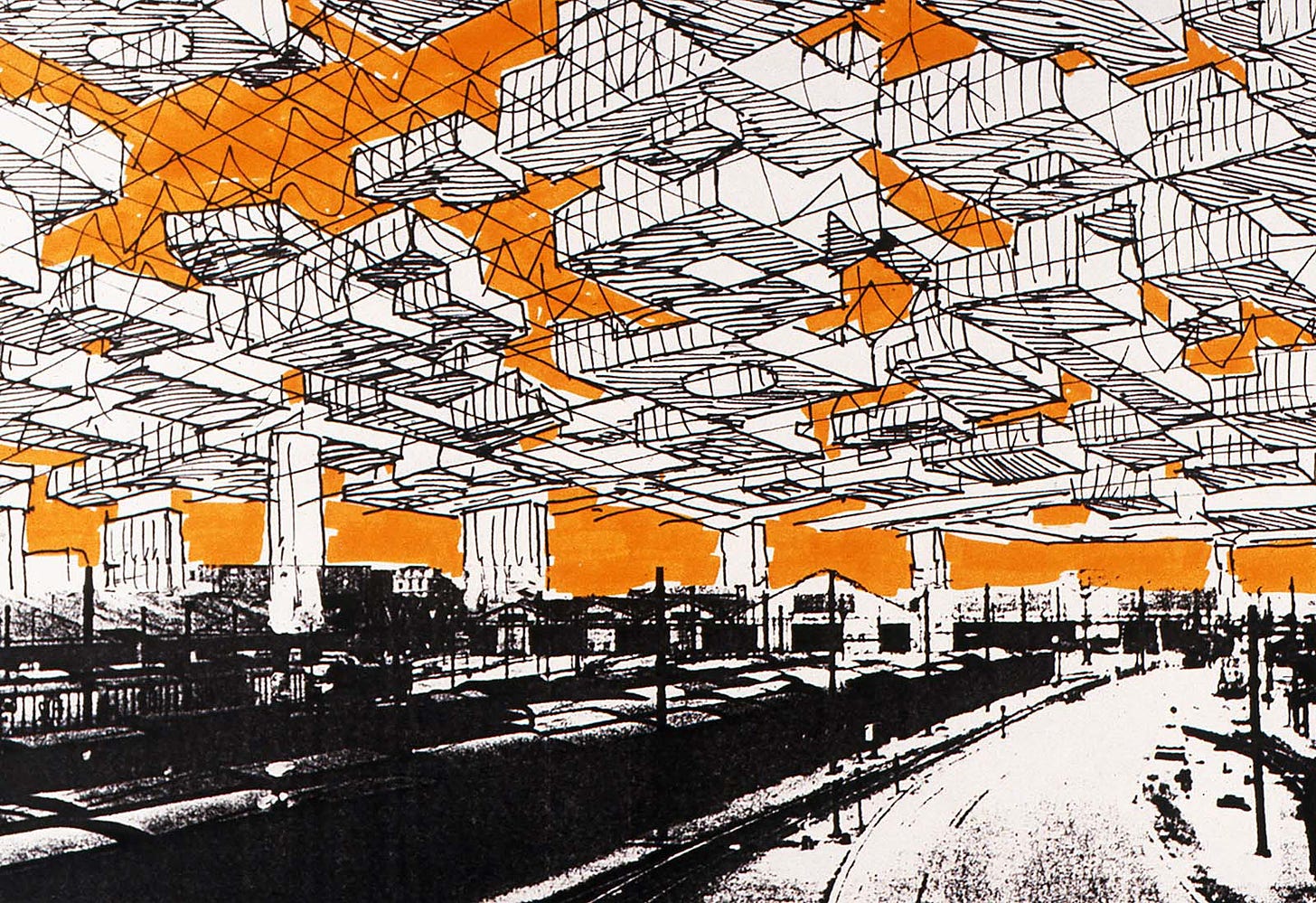

Doctorow correctly points out that the internet is being reordered. Initially, the dream was that it would “disintermediate everything.”26 To speak in Alexander’s language, the internet would have been a virtually endless semilattice of dynamic and overlapping parts. Instead, a few large platforms re-intermediated the internet and introduced ways to be the sole arbitrator between people online. And so, the richness of what could have been a complex, global semilattice atrophied into a circle-like shape made up of a few central nodes. Information in this arrangement resembles a closed loop, and the user is often just carried by the stream. And it goes without saying that you can only go around a loop a few times before things get stale.

The internet hasn’t become a tree, but there are certainly those who would like it to resemble one. Both leading tech platforms and governments believe themselves to be capable of containing information and separating its parts. The process started in earnest after the Arab Spring (2010-2012), when it became clear that online activity could produce shocks with real-world consequences. A growing pessimism about technology in the hands of the public developed at the top, as the interests of both “public safety” and profit converged to more deliberately plan the internet and mediate its branches. Simply put, complex systems are easier to surveil when information is neatly siloed into branches. It also simplifies data collection for advertisers.

While tree-like thinking is being imposed on online life from above, it is also true that the internet is deficient in its ability to be a semilattice. As Alexander writes, “overlap is a vital generator of structure.”27 Overlap on the internet is made possible through search and indexing which has, in almost all cases, badly declined.28 Google, as the leading indexer, has been the prime target of enshittification despite its market dominance increasing.29 Additionally, most platforms are walled gardens that are not easily searchable, their content only being found because it was reposted in another walled garden. Platforms have an interest in making sure users stay in their domain as much as possible. This makes overlap especially difficult by design, and so much of the internet now exists as islands on the periphery as a result. Effectively, that which would make a semilattice of the internet dynamic and alive is being dismantled.

According to Alexander, “the city is a receptacle for life.”30 That is to say, the structure of the city creates the life of its people. Every time a city trades its “humanity and richness… for a conceptual simplicity which benefits only designers, planners, administrators, and developers,” so, too, does the individual lose that same depth.31 In such circumstances, the city and the life of its people “take a further step toward dissociation.”32 Alexander intentionally uses the language of psychology to describe this damaging process:

In any organized object, extreme compartmentalization and the dissociation of internal elements are the first signs of coming destruction. In a society, dissociation is anarchy. In a person, dissociation is the mark of schizophrenia and impending suicide.33

Like a city, the internet is a receptacle for life, and how it organizes itself has consequences for the psychological well-being of its users.

The Internet Is Like a City

The internet doesn't need to be understood in urban metaphors. There are no neighborhoods, no downtowns, no highways connecting its metropolises. But the internet is like a city in a more fundamental way, in that they both derive their life from the meaningful overlap of their many parts.

Some have spoken of the internet not as a semilattice, but as a rhizome or plant stem with connecting roots and nodes.34 Others have instead compared it to fungal networks that live deep underground in symbiotic relationships.35 And still others have likened it to swarms, organizing activity spontaneously without coordination.36 Regardless of what name you give it, the internet is dynamic because of its multiplicity and uniquely limitless overlap. And this fact alone means that the internet can never completely be made into a tree. Its many overlapping parts may be in decline, but they will persist because someone will always seek them out.

A City Is Not a Tree gains a new, deeper meaning when read today. It shows that the order of a system gives rise to its greater structure and life. This simple truth impacts every aspect of its flourishing, both for a city and for the internet.

Other essays on the internet »

The first public conference on the internet in 1994 was called the Superhighway Summit, intended to be a dialogue about the “information superhighway” (as the internet was called then).

William J. Mitchell not only believed the internet to be a new kind of city, but he thought the internet would do “what the agora did in the life of the Aristotelian polis.” It was to be the most ambitious and far-reaching public space ever conceived.

Christopher Alexander. A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition (Sustasis Press), pg. 1.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 1.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 1.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 3.

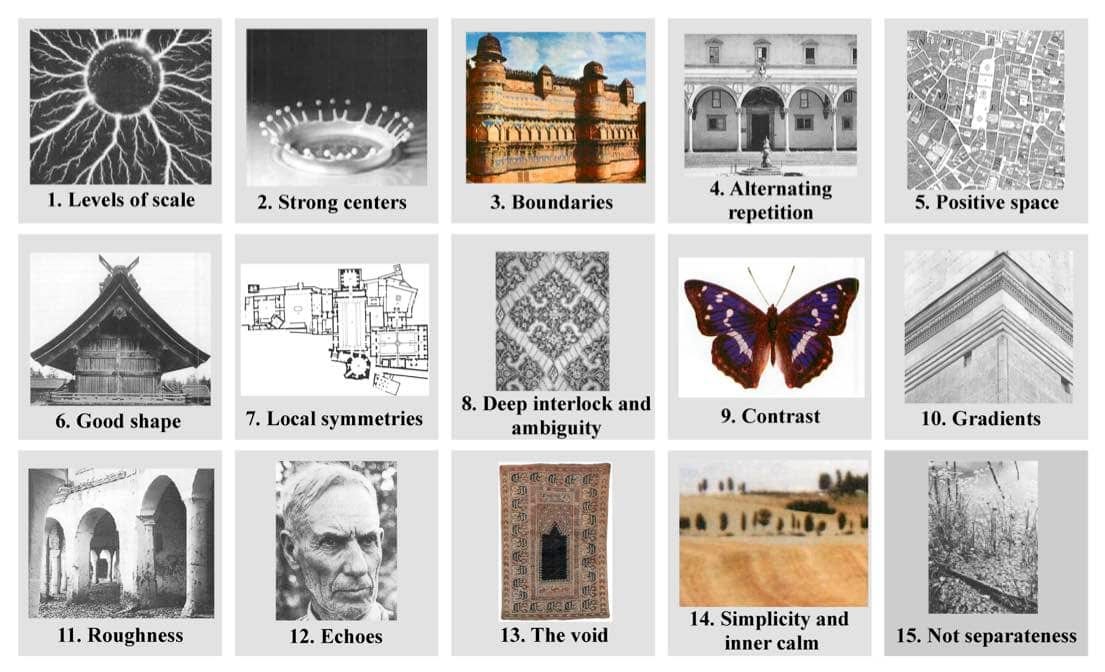

Alexander’s theories on order, form, and beauty primarily take inspiration from nature and mathematics. He believed there were universal lessons to draw upon that could guide us in creating more liveable spaces. In The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe (2005), he identifies fifteen fundamental properties in living structures that inspire, visible across many different contexts and cultures.

On pg. 24, Alexander writes: “The total separation of work from housing, started by Tony Garnier in his industrial city, then incorporated in the 1929 Athens Charte, is now found in every artificial city and accepted everywhere where zoning is enforced. Is this a sound principle?”

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 8.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 17.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 16.

America especially has seen the decline of its third places, those places to socialize that are neither work nor home.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 9-15.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 26.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 26.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 28.

Alexander’s essay received many responses, some of which disputed whether a city really was a semilattice. However, they still highly valued his original work and the questions it posed.

There are many instances where tree-like structures could be useful for understanding, like within the realm of physical science or whenever hierarchy is strictly necessary.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 30.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 31.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 31.

This has been an ongoing conversation for years now, but it is pretty much definitive that the quality of Google searches and indexing has plummeted.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 32.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 32.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 32.

A City Is Not a Tree: 50th Anniversary Edition, pg. 32.

In the early-to-mid 2010s, the populist protest wave organized online was likened to a swarm.